A History of Stunts

Ryan Gosling’s new film is a love letter to an under-appreciated art.

The Fall Guy juggles the genres of thriller, mystery, and romantic comedy with aplomb—the thriller is exciting, the mystery is clever, and the rom-com is sexy and funny. Together, they make for an exuberant celebration of the performers who risk their lives for a “gag” (the professional’s term for a stunt). As an action extravaganza, The Fall Guy connects us to our childhoods—those reckless years we were lucky to survive—and invites us to imagine adulthoods with the courage to gamble security for dreams.

The filmmakers know that flirting with danger is human nature. As a kid growing up in the 1950s, a friend and I dared each other to cross a railway trestle over the Avon River. “What if there’s a train?” “We’ll hear it coming.” “What if we’re in the middle and can’t get back?” “We’ll lie flat, and the train will run over the top of us.” The scariest part was looking down at the river rocks through the gaps between the ties. Sixty-plus years later, the thrill of that childhood dare remains vivid.

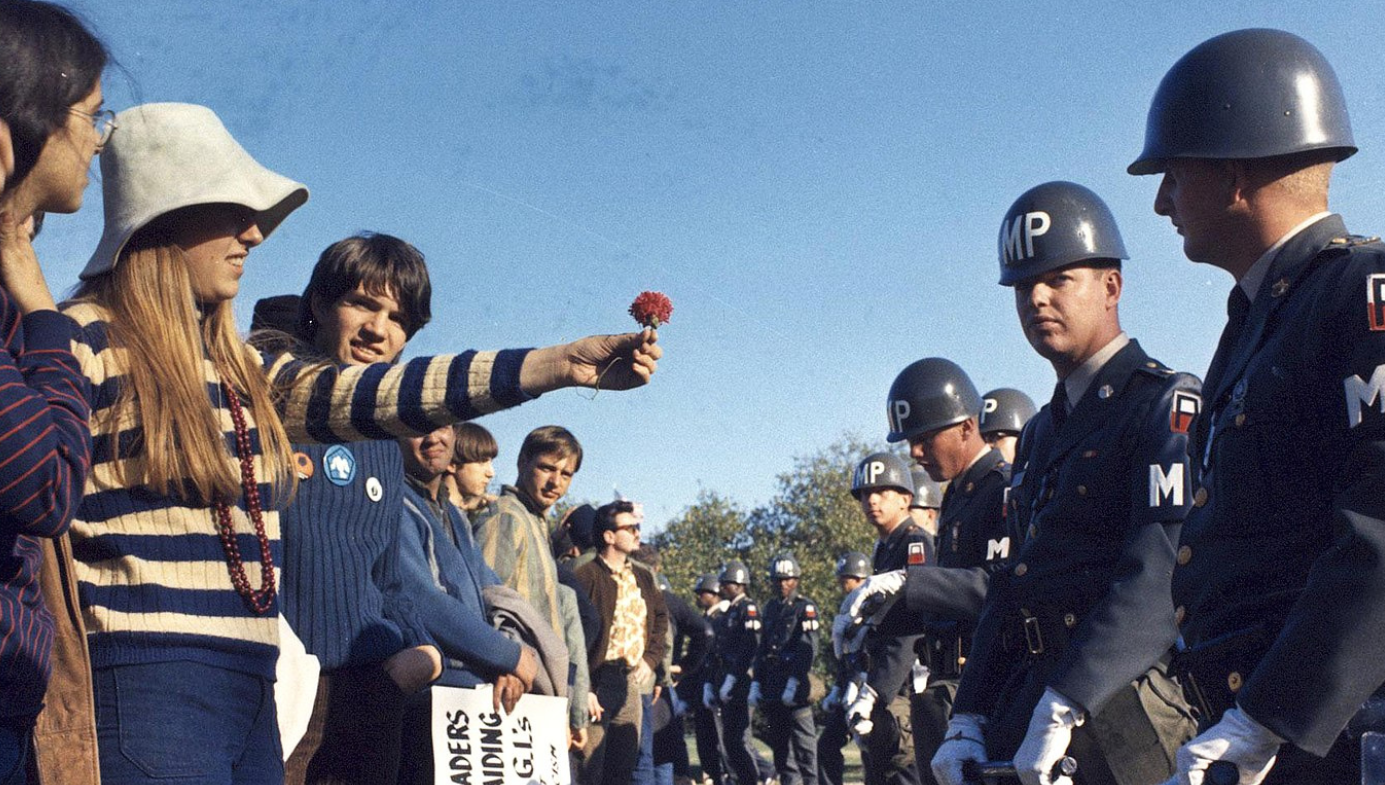

TikTok Challenges and attempts to replicate stunts seen on the Jackass franchise prove that nothing has changed. No matter how well-supervised, kids will still find ways to endanger their own safety that sometimes kill them. So will adults, of course, as shown by the popularity of skydiving, rock climbing, and extreme skiing, not to mention the hundreds of thousands who vie to appear on shows like Survivor, Fear Factor, America’s Funniest Home Videos, and earlier iterations like Wildboyz and World of Stupid.

There have always been fall guys and audiences for their stunts. In a Bronze Age version of running with the bulls, young Minoans performed somersaults off the backs of charging bulls as a rite of passage. To ward off drought, Aztecs danced for the gods while dangling upside down by a foot tied to the top of a rotating 90-foot pole. (Today, the Voladores ritual is a tourist attraction.) And high wire acts and “ventadores” (exotic matadors who fought lions, elephants, and cheetahs) were featured at the Roman Colosseum.

When a young acrobat fell to his death, Emperor Marcus Aurelius ordered that mattresses be placed under tightropes. But the greater the danger, the greater the stakes, and playing for one’s life is the greatest stake of all. That is why death-defying stunts provide the biggest thrill for daredevils and audiences alike. It’s no doubt why European circuses performed without nets until the mid-19th century. Charles Blondin was delighted that the crowd who watched him tightrope across Niagara Falls in 1859 had placed bets on whether or not he would die in the attempt. Blondin believed that a rope-walker was “like a poet, born not made” and that security precautions provided false confidence, which made falls more likely. That is also the credo of The Flying Wallendas, despite the multiple tragedies the family has suffered over the years. Two died in a 1962 fall with the Shrine Circus; patriarch Karl perished at 73, crossing between two condo towers; and five more Wallendas were seriously injured in recent memory.

Men may be more reckless by nature, but women accomplished two of the greatest early-modern stunts. In 1877, 17-year-old Rossa Matilda “Zazel” Richter became the first human cannonball. Her spring-loaded cannon was invented by the Great Farini (aka Canadian William Leonard Hunt). It “hurled her from the jaws of death into the arms of fame” and led to tours throughout the United States and Europe where she played to audiences of 20,000 people. Sadly, Richter broke her back in a tightrope act.

Annie Edson Taylor was an amateur but she was no less accomplished. On her 63rd birthday, she became the first person to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel. A widow and itinerant teacher, Taylor counted on the 1909 Buffalo World’s Fair to provide a crowd and the means to see her through retirement. Unfortunately, her manager stole her barrel and toured it with a young impersonator. She lost what little money she had in its recovery, only for it to disappear again. Ironically, Taylor ended her days as a clairvoyant.

The rough and tumble lifestyle of stunt performers was made for early motion pictures, since the new medium relied upon physical action. Talent wasn’t a requirement. If a director needed someone to hang off a roof, they’d find an untrained showoff; these amateur extras were known as “Bump Men,” presumably because so many got bumped off. But professionals were clearly a more reliable option. Wild West shows had developed a large talent pool of trick riders like Tom Mix and Frank Hanaway, who became the first officially credited stunt man in The Great Train Robbery (1903).

The physical slapstick of vaudeville clowns like Chaplin and Harold Lloyd found an equally natural home in motion pictures. The most daring of these was Buster Keaton, whose stunts are as shocking as they are comic. Ironically, safety devices were first used in the 1923 Harold Lloyd vehicle Safety Last! Keaton would have none of it. In Steamboat Bill Jr. (1928), the two-ton façade of a house falls on top of him, but his mark coincides with the open second-floor window. Keaton only allowed two inches of clearance on each side. Years after the fact, he discovered he’d broken his neck while shooting Sherlock Jr. (1927) when the deluge he released from a water tank pummelled him onto a railway track. Meticulous in his planning, Keaton took physical risks into his final year, when he made the National Film Board of Canada’s comedy short The Railrodder. (A terrific “making of” documentary shows his preparation and disdain for safety precautions.)

Audiences, then as now, loved to see stars perform their own stunts. But as stunts became more dangerous, studios began to worry about killing or maiming the actors in whom they’d invested time and money. Contracts for stunt doubles included a non-disclosure clause to ensure they remained anonymous. This added to the heroic myth of the action star while the studios continued to ignore the cost of stunts in human and animal life, a situation depicted in Damien Chazelle’s underrated 2022 period picture, Babylon.

Yakima Canutt did much to change that. Regarded as the greatest stuntman and second-unit director of all time, he doubled for stars like John Wayne and Clark Gable. It was Canutt who drove the wagon through the flames of Atlanta in Gone with the Wind, and who devised and performed the electrifying drag in Stagecoach (analysed here). He was also responsible for innovating a number of safety devices like the L-stirrup, which lets riders fall off horses without getting tangled in their gear, and a cable-release system that frees teams of horses before their wagons crash. Canutt also designed the stunt sequences in epics like Spartacus, El Cid, and Ben Hur (1959). He took a year to prepare the latter’s epic chariot race which involved a full production team to train the 78 horses and their charioteers.

Contrary to legend, not a single actor or horse died in that chariot race. That horror belongs to the 1925 silent version of Ben Hur, which saw the death of a stunt man and a hundred horses, as well as the reputed drowning of three extras when a ship caught fire during its sea battle. But an “unplanned incident” during the 1959 film’s chariot race nearly took the life of Canutt’s son, Joe, who doubled for Charlton Heston. Joe was to ride up a small ramp and sail over the wreckage of two chariots. Instead, he was propelled into the air, luckily escaping with no more than a cut chin. Director William Wyler filmed a clip of Heston recovering control of the chariot. It was edited into the film and made the accident the highlight of the race.

Stunt performers began to organise in the 1930s. Tom Steele helped to create The Cousins, a collective established to lobby for better insurance policies and pay rates from studios, and the elimination of Bump Men. Steele was keen to professionalize the field. Whereas earlier stunt men had taken macho pride in their injuries, he introduced “stunt pads.” This protection meant that a performer could take on more work or other pursuits—old injuries prevented Steele from serving in World War II.

In 1961, the invitation-only Stuntmen’s Association of Motion Pictures was formed for male members of the Screen Actor’s Guild. This attempt to create an all-white all-male closed-shop union provoked the creation of The Stunt Woman’s Association and the Black Stuntmen’s Association in 1967. The latter ended “Paint Downs,” in which white performers did stunts in black, brown, and yellow face. “Wigging” (men wearing wigs to do stunts as women) remains an issue.

As stunt work professionalized, some stunt men became stars, like the legendary Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, both of whom helped to popularise martial arts in North American action films. Others, like Burt Reynolds’ longtime stunt double and friend Hal Needham, became director/screenwriters. When Needham gave Reynolds a script he’d written, Reynolds agreed to star with Needham as director. The result was Smokey and the Bandit (1977), a smash hit that led to a seven-film, 20-year collaboration. (Their friendship provided the model for the DiCaprio/Pitt star/stunt-double relationship in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood.)

Things eventually began to come full circle. Stars increasingly wanted to be seen performing their own stunts. Today, Tom Cruise is probably the most famous example of this trend. The promotional short about his motorcycle jump in Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning Part One is amazing. Keanu Reeves is no slouch, either; he does 90 percent of his own stunts in John Wick. And a number of stars have suffered broken bones, herniated discs, and concussions, and have needed surgeries to own their heroics.

The legendary Evel Knievel made daredevils a part of celebrity culture. His 433 fractures had earned him a place in the Guinness Book of World Records for “Most Broken Bones in a Lifetime.” This public fascination with stunt men led to Peter O’Toole’s The Stunt Man (1980) and Lee Majors’s ABC television series The Fall Guy (1981–86) about a stunt man who moonlights as a bounty hunter. Every show featured Majors’s hero Colt Seavers tracking down bad guys while pulling serious, practical stunts in his GMC Sierra.

The Fall Guy was a middling TV success but never a major hit, sitting in the Neilson ratings’ top 30 at a time when there were only three networks producing shows. So, it’s not especially surprising that it is one of the last 1980s’ series to get the Hollywood treatment. Director David Leitch’s The Fall Guy is to action films what T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is to literary references, and a good deal more fun. This is no surprise given his background. Like Hal Needham, Leitch began his career as a stunt man (his resume includes doubling for Brad Pitt in Fight Club and Matt Damon in The Bourne Ultimatum) before he became the critically acclaimed, billion-dollar director of action hits like John Wick, Deadpool 2, and Bullet Train. With passion and high spirits, he draws on the legacy of history’s greatest stunt artists with practical, death-defying gags rather than CGI effects. It’s an effective pitch for the ongoing campaign to see stunt performers and coordinators recognized with an Oscar at the Academy Awards.

Leitch says The Fall Guy is not a reimagining of its source material but a prequel. His Colt Seavers (Ryan Gosling) is a stunt man ostensibly hired to double for the star in the first movie directed by his ex-girlfriend, Jody Moreno (Emily Blunt). But the real reason is to find the star, who’s gone missing. If Seavers can’t do it in two days, Jody’s film will be cancelled. So, off he goes on an adventure that involves jumping and rolling his GMC Sierra, falling from great heights, and crashing through windows and furniture, all while defending himself against armed thugs, martial artists, and general mayhem. Periodically, Jody makes an appearance to remind us that she’s still in the movie, but Leitch has tossed their rom com in the back seat for the highs of a mystery/thriller joyride. (Happily, she returns for a finale that sticks the landing.)

The giddy plot is full of holes, but the stars’ charisma and the general excitement ensure that this doesn’t matter much. Leitch crams the running time with inspiration from classic stunts and attempts to break their records. The first truck jump is a tip of the hat to the series’ signature stunt, while the spectacular climax jump pays tribute to Smokey and the Bandit and Hooper. Still, the most dangerous vehicle gag is Logan Holladay’s eight-and-a-half cannon rolls, which surpasses the previously record-breaking seven in Casino Royale. For this stunt, a modified cannon was attached under the car. When triggered, it explodes downward, propelling the speeding vehicle into the air. To reduce the chance of injury and death, stunt coordinators calculate the combination of the car’s weight, the cannon’s force, and the angle and condition of the road. But a somersaulting vehicle can have ideas of its own.

Other thrills include Troy Lindsay Brown’s 150-foot fall from a helicopter, a tribute to Sharky’s Machine and Assassin’s Creed. A garbage bin free-for-all over Sydney Harbour Bridge is inspired by the truck chase in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Do stay for the credits. As they roll on the right of a split screen, we see the film’s stunts replayed on the left, this time with the wires and harnesses in place. Just as Penn and Teller’s deconstruction of magic adds to our appreciation of their tricks, so this sequence reminds us of all the effort and skill it takes to make an art look easy.