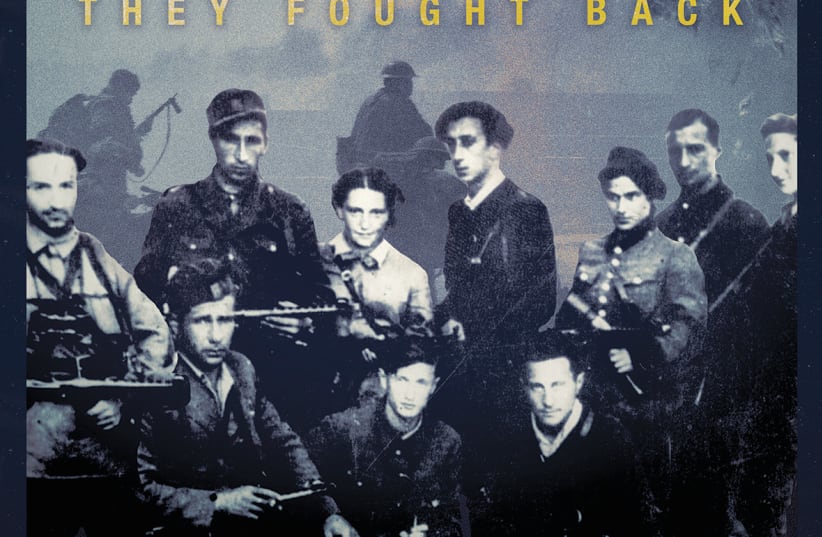

Boston-based filmmaker Paula Apsell’s powerful new documentary, Resistance – They Fought Back, featuring relatively unknown stories of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust, will be aired on HOT 8 in Israel on Holocaust Remembrance Day, May 6. Abramorama released the film, which features narration by actors Corey Stoll, Dianna Agron, and Maggie Siff, in New York on April 12.

“We’ve all heard of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, but most people have no idea how widespread and prevalent Jewish resistance to Nazi barbarism was,” says Apsell.

Professor Richard Freund adds, “Instead, it’s widely believed that ‘Jews went to their death like sheep to the slaughter.’ Filmed in Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Israel, and the US, Resistance – They Fought Back provides a much-needed corrective to this myth of Jewish passivity. There were uprisings in ghettos large and small, rebellions in death camps, and thousands of Jews fought Nazis in the forests. And everywhere in Eastern Europe, Jews waged campaigns of nonviolent resistance against the Nazis.”

In 2018, Apsell won a Lifetime Achievement Emmy for her accomplishments as executive producer of the prestigious PBS science series Nova. I interviewed her by email.

What motivated you to produce the documentary?

I was executive producer of the PBS Nova science series for almost 35 years. For a film that we made in 2016, I went on location to Lithuania to Vilnius, the capital, called Vilna in Yiddish. A few kilometers out of town there’s a forest called Ponari, which is a place where the Germans and their Lithuanian collaborators shot and killed about 70,000 Jews and 30,000 others. My co-director Kirk Wolfinger and I were with a group of geoarchaeologists led by Prof. Richard Freund, a Jewish historian, rabbi, and archaeologist. They were looking for an escape tunnel that was rumored to exist. They were using very high technology equipment which can peer into the ground without digging, essential when working in a place where Holocaust victims are buried. You don’t want to desecrate their bodies a second time.

When I was at Nova, I always used to talk about the ‘moment of discovery,’ but it actually never happened to me. I was never in any lab or any place where anybody discovered anything; but in this case, using this electronic equipment, the geoarchaeologist actually confirmed the existence of this escape tunnel dug by 80 Jewish prisoners who had been conscripted by the Germans to exhume and burn the bodies of the thousands of Jews the Germans and their Lithuanian collaborators had murdered. On the last night of Passover, which the rabbi told them was the darkest night of the month, the prisoners used the tunnel they had dug at night with spoons to try to escape. Twelve succeeded and made it out to the forest, where Abba Kovner and the partisans were waiting. The rest of the 80 Jews who were prisoners in this place were shot. Finding that tunnel – which The New York Times called one of the 10 most inspiring science stories of 2016 – was a transformational moment for me. I started to think why I didn’t know about this example of Jewish resistance in the most dangerous place imaginable – they all easily could have died – and I had never heard of it or any other tunnels or any other examples of Jewish resistance, with the exception of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. I started doing some research, and when I retired from Nova in 2019 – my husband, Sheldon, says I flunked retirement – I decided that I would make an independent documentary on Jewish resistance during the Holocaust because during my research I had found so many amazing examples, and I really wanted to tell that story. For a variety of reasons, so many people believe that Jews went to their deaths, you know that old saying, ‘as sheep to the slaughter,’ as passive victims. It’s a myth that has taken hold, and I wanted to show that it’s simply not true, and that’s why I made Resistance – They Fought Back.

How did you put it all together?

Jewish resistance was not something that was fully baked from the start when the Germans started placing Jews in ghettos; it’s something that evolved as conditions changed and as people’s perceptions of the situation changed. Jews in the ghettos had no weapons; they had no way to fight the Germans with arms, but they still resisted in ways that they always had historically. They fed the hungry; they took care of orphans; they kept track of German war crimes so there would accountability at the end of the war and so that people would know exactly what the Germans had done to the Jews of Europe. This unarmed resistance is known in Hebrew as amidah, or ‘standing up against.’ It also consisted of cultural activities. There were plays, there were orchestras; the ghettos were places of amazing activity. The lending library in Vilna was never so busy as during the Holocaust when the Germans placed Jews into ghettos. There were no schools, and so they ran schools for children, insisting that children be educated so that they would develop as human beings and as Jews after the war. And there was spiritual observance. At the beginning, people in the ghettos did not understand that the end goal of the Germans was the extermination of all the Jews in Europe. We know it by hindsight, but really, who could imagine such a thing? Who could conceive of such a thing? But as the Germans began to deport Jews to death camps starting in 1942, and it became clear what their goal was, then Jews in the ghetto led by the young, by people barely out of their teens, started to collect arms and plan for armed resistance. This eventually led to uprisings in many ghettos, not just the Warsaw Ghetto; and as the Germans ‘liquidated’ the ghettos, Jews escaped into the forests, becoming partisans, mounting guerrilla actions against the Nazis, which kept the forest available for Jews to use to hide and escape. There were eventually 30,000 Jews fighting in the forest; and, of course, later, as many Jews were already dead and those who weren’t were in death camps, this led to rebellions in death camps.

There was a certain chronological order to this which we followed in the film. Nonviolent resistance eventually evolves into armed resistance in ghettos and then in the forests, and that eventually evolves into resistance in the camps. I, by the way, knew very little about resistance in the camps, which is really unfortunate, since out of seven death camp rebellions, six were led by Jews. They are, of course, written about in the scholarly literature, but somehow, like so much of Jewish resistance, have not penetrated popular culture. There have been a handful of feature films about these uprisings. There was a film about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and one about the rebellion in the Sobibor death camp (Escape from Sobibor) and, of course, there was Defiance, about the Bielski Brigade in Belorussia, a wonderful film. But those were all produced quite a while ago. The Sonderkommando Uprising in Auschwitz, which I certainly had never heard about, took place on the tragic date of October 7, 1944. It destroyed a combination crematorium and gas chamber and, by doing so, probably saved many lives, although the rebellion itself was brutally put down.

The film Resistance – They Fought Back is organized into three sections – Amidah, or Unarmed Resistance; Armed Resistance; and Resistance in the Camps – and follows the story chronologically. To some extent, the way a film like this comes together depends on the people that you have to tell the story. We were very fortunate that we had wonderfully articulate scholars, we had five survivors who were involved in some way in Jewish resistance, and we had notably the children of survivors, which in some way extends authentic first-person Holocaust knowledge by another 20 years.

Is there any particular story that you find most striking?

I really love all these stories, but I suppose what I think is unique about the film is that it does give equal time to amidah, the first phase of Jewish resistance, based on acts of charity, cultural activities, and spiritual observance, which was done without weapons, helped elevate the spirits of the Jews in the ghettos, made things more difficult for the Germans, and eventually set the stage for armed uprisings. And then there’s the emphasis on the essential role of women in the resistance. Vladka Meed was a courier in the Warsaw Ghetto, sent outside the ghetto to pose as a gentile and procure weapons for the uprising. [There was] a young woman, a 19-year-old named Bela Hazan, who was also a courier. She smuggled weapons, people, messages from ghetto to ghetto, going outside the ghettos where men could not because they were so easily identifiable as Jews. Even after being caught and tortured by the Germans and sent to Auschwitz, Bela continued to save lives, smuggling young Hungarian women under the fence into the women’s camp, saving them from the gas chambers. The importance of this is to demonstrate that Jews rescued Jews, even at the risk of their own lives, an idea that seems to have been lost.

What is it that you hope to convey to the larger audience?

It’s the idea that Jews fought back. It’s very simple, it’s right in the title, Resistance – They Fought Back. Indeed, two-thirds of European Jewry died, six million buried in places known and unknown in Europe, a catastrophe for the Jewish people. But before they died, they fought back. I wanted to show the idea that Jews went to their deaths like sheep to the slaughter as the myth that it is. And it is, by the way, a very dangerous myth because antisemites and white supremacists, if you read their crazy rants, you see that tied up with their hatred they believe that Jews are people without courage who will not fight back. That wasn’t true during the Holocaust, and it isn’t true now.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

The Holocaust, or Shoah, is an enormous event in modern Jewish history, and it will remain an important part of who we are as Jews for a long time to come. Therefore, I personally believe that in Holocaust education and even in our remembrance on days like Yom Hashoah, we need to emphasize that Jews did fight back – and I’m not talking about small numbers or rare events. I’m saying from my research that under the most horrendously difficult circumstances, they fought back in the ways they could, systematically and communally. I think this is an essential to build Jewish pride and identity, especially among the young. I cannot tell you how many people have told me that as young Jews they could not bear to think about the Shoah because it made them ashamed when they learned that Jews went to their deaths ‘like sheep to the slaughter.’ Professors tell me that when they ask their students what they know about the Holocaust, that’s what they hear, that Jews were passive victims. I think the heroic stories of Holocaust resistance needs to become a greater part of our legacy, something we teach our children as their heritage, and we need to promote it to the public at large through films and stories that will become embedded in popular culture. It’s a challenge, but it’s an important one, affecting both how Jews think of themselves and how others in our communities think of Jews.■