Is Geneva still the capital of peace?

As multilateral diplomacy and Swiss neutrality come under pressure, Geneva’s reputation as a place of peace is also at risk.

“Geneva, capital of peace.” The slogan is well known to journalists accredited to the Palais des Nations, the United Nations (UN) office in Geneva. But is it still relevant today? “It’s been a few years since we saw any negotiations here,” laments a colleague, whose work frequently takes him to the Palais.

Until 2022, the international press went regularly to the UN’s European headquarters to follow progress in the negotiations on Syria. Since 2015, rounds of talks on Yemen have sporadically attracted strong media interest. In 2020, a ceasefire for Libya was even signed there.

Today, however, most of the peace processes under way on the shores of Lake Geneva seem to have stalled. This may be blamed on unsuccessful multilateral diplomacy, but also Russia’s efforts to boycott Geneva.

Moscow, which no longer considers Switzerland to be neutral since the start of the war in Ukraine, obtained the suspension of talks on Syria, a close Russian ally, in 2022. In April of this year the Kremlin threatened to move negotiations on Georgia, usually held within the UN, to another country.

More

Newsletters

Geneva is also feeling the brunt of geopolitical changes, including a recalibration of the international order – from west to east, and from north to south. Other countries and capitals also want to pull their weight on the world stage.

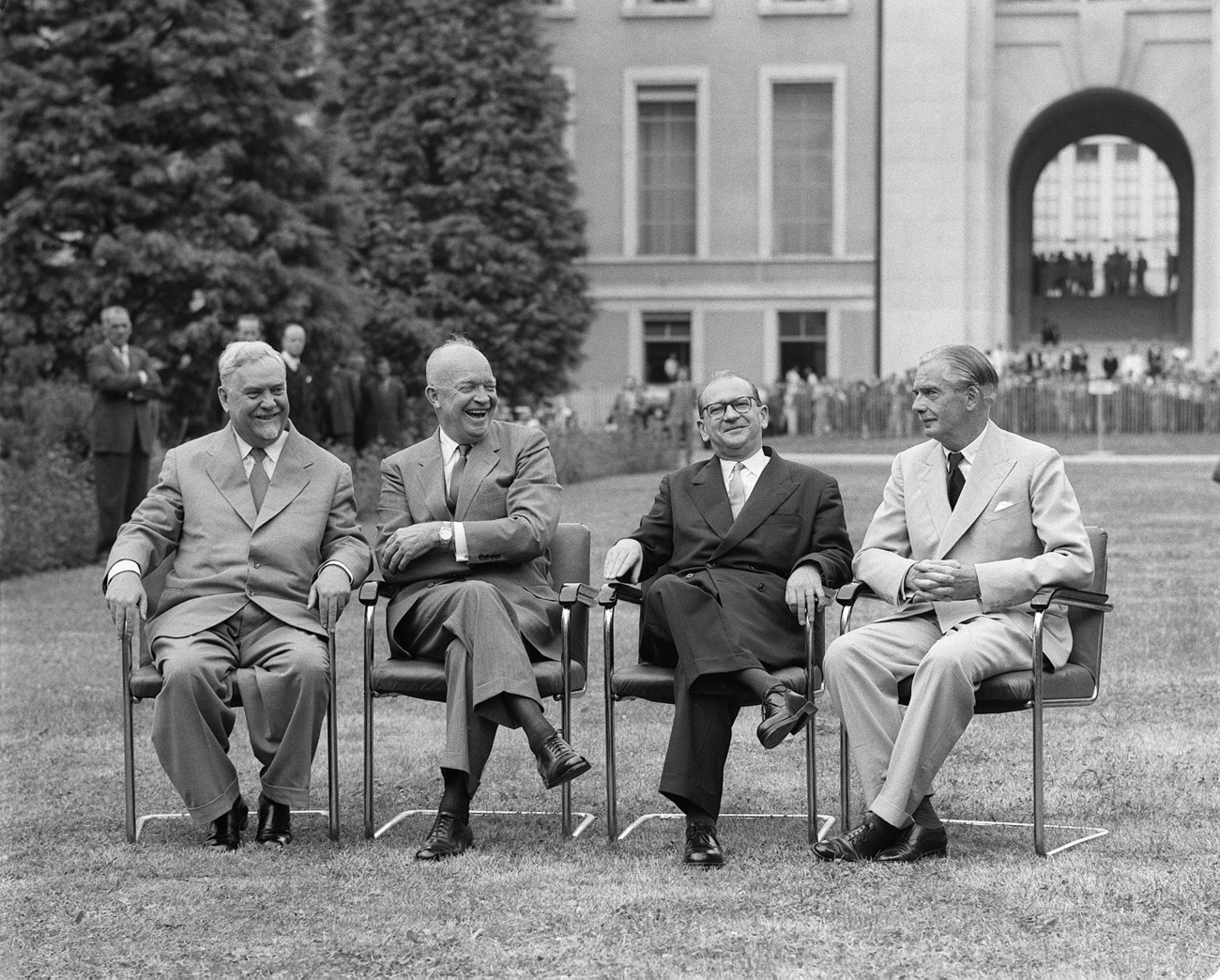

The era of the major meetings, for which Geneva is renowned, appears to be over. The 2021 summit between US and Russian presidents Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin was nothing like the 1985 one between US and Soviet leaders Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, held in the midst of the Cold War. The 2021 meeting was a “non-event”, according to a well-informed source who prefers to remain anonymous.

More

Biden-Putin summit: Why Geneva?

Changing world order

The organisations of International Geneva, which also hosts the headquarters of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the International Committee of the Red Cross, are largely based on a world order established after the Second World War. This order, dominated by the United States, is now being challenged by China and Russia, as well as certain African and South American countries.

“If this world order loses its dominance, clearly Switzerland and Geneva will also lose their importance,” says Daniel Warner, former deputy director of the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies (IHEID). “And the blockages in the Security Council are tarnishing the UN’s image as a peace negotiator, which has an impact on International Geneva.”

As the main body responsible for maintaining world peace, the Security Council in New York is paralysed in most conflicts because of the veto rights of its five permanent members and rivalries between the major powers.

International competition

“In the past, when people wanted to meet to negotiate peace, they immediately thought of Geneva. This seems no longer to be the case,” laments Georges Martin, a former Swiss diplomat and former number three at the Swiss foreign ministry. “There is a negative dynamic. And as Geneva loses its influence, other countries are happy to take its place.”

Thus, the agreement on Ukrainian grain exports via the Black Sea was signed in Istanbul, with Turkish mediation. Qatar, meanwhile, recently hosted negotiations on a possible ceasefire in Gaza.

While geographical or political proximity may explain these states’ entry onto the diplomatic stage, Martin believes it is also a consequence of the Swiss government’s foreign policy, which, he says, is damaging the country’s reputation of neutrality.

What about Swiss neutrality?

Swiss neutrality has always been one of Geneva’s main assets as a meeting place for warring parties. But Switzerland has struggled to assert this neutrality on the international stage since the resumption of European sanctions against Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine.

For the past two years, the Kremlin has repeatedly stated that it no longer considers the country to be neutral. In March, its representative to the UN in Geneva, Gennady Gatilov, announced that Moscow would not take part in the conference on the Ukrainian peace plan that Switzerland will hold in June at the Bürgenstock resort above Lake Lucerne. Russia has so far not been invited to the talks.

More

Switzerland to host Ukraine peace conference in June

It is, however, not the first time the Swiss government has adopted sanctions outside the UN to punish a state for violating international law. Switzerland sanctioned Libya in 2011, for instance.

Divisive decisions

Since the outbreak of the war in Gaza on October 7, the Swiss government has taken several decisions that part of the Swiss political class considers contradictory to the country’s humanitarian and neutrality traditions.

In January the government temporarily suspended its funding to the UN agency for Palestinian refugees (UNRWA), after Israel accused some of the organisation’s employees of involvement in the Hamas attack on the country.

Last November Bern also decided to ban Hamas in Switzerland, thus making it more difficult for the parties involved in the Middle East conflict to negotiate on Swiss soil.

More

What are the allegations upending UNRWA’s aid efforts in Gaza?

Some critical voices, particularly in the academic world, argue that Switzerland, the depositary of the Geneva Conventions, took too long to firmly denounce Israel’s violations of the laws of war in Gaza.

“I know that at the UN in New York, and beyond, people are asking: where is Switzerland? What does it think? What is its policy? We’ve lost credibility, clarity and predictability,” former Swiss diplomat Martin insists. “Switzerland is perceived less as a peacemaker, and this inevitably has repercussions on Geneva.”

Lack of leadership

According to Martin, the stormy debates in parliament on the possibility of re-exporting Swiss weapons to Ukraine, on the use of interest from Russian assets frozen in Switzerland, and on funding for UNRWA are the result of a lack of leadership by Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis, in office since 2017, in explaining the Swiss government’s positions to the members of parliament.

This criticism is contested by Laurent Wehrli, Radical-Liberal parliamentarian and president of the foreign policy committee. “I don’t feel that my colleagues don’t know what the government’s positions are,” he says. In his view, foreign policy is currently “polarised”, with part of the right and the left hijacking foreign policy issues to serve domestic political interests.

Moreover, Wehrli adds, International Geneva has “if anything, gained” in recent years, thanks to parliament’s decisions to finance the renovation of the headquarters of some organisations and the development of digital governance. “These are concrete examples that show that Mr Cassis and the government have succeeded in explaining to parliament the importance of International Geneva,” he stresses.

More

Switzerland drops the Geneva Initiative. But what’s the alternative?

Meanwhile, Carlo Sommaruga, a Social Democrat senator from canton Geneva and vice-president of the foreign policy committee, is critical of Cassis’s policy, which included dropping the Geneva Initiative on the Middle East. Yet he says he is not worried about the consequences on the role of International Geneva more broadly.

“Geneva is still an attractive venue. With everything it has to offer, many players still come here,” he says. “It is important to distinguish between International Geneva as a platform that Switzerland can provide as a host state for conferences, where it is not necessarily a player, and Switzerland’s mediation role.” This role, Sommaruga stresses, is currently out of the question with regard to the wars in Ukraine and Gaza.

New ways of thinking about peace

While the political UN is suffering, with negative repercussions for Geneva, its technical agencies are doing “relatively well”, according to Michael Møller, former UN director in Geneva. Some 40 of them, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), are headquartered in Geneva. Their respective roles are to promote health, working conditions around the world and access to the web.

According to Møller, these organisations have rarely done as important a job as they do today.

“Making peace is not just about sitting down and trying to put a stop to the fighting. Put simply, it means implementing all the sustainable development goals,” he stresses. This is a reference to the 17 goals that the world community has set itself, in particular to eradicate poverty and combat climate change.

“We need to move away from the traditional way of thinking about peace and approach it more broadly.” Møller believes that peace cannot come about as long as inequalities persist, whether in terms of access to healthcare, education, work or a healthy environment. These are all fields in which International Geneva is actively working.

Negotiations far from the public eye

“Most peace negotiations take place behind the scenes,” Møller adds, and countries in conflict continue to meet in Geneva “very discreetly, without anyone knowing”.

This confidential dialogue takes place at the UN, but also within private mediation organisations, such as the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) and the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP). These structures help organise meetings between players who wish to talk to each other outside official channels, enabling a dialogue that is particularly useful when formal diplomacy is not possible.

More

‘Negotiating with the Devil’: What it takes to be a peace mediator

“So-called private diplomats have filled a certain void,” confirms David Harland, the executive director of HD and a former New Zealand diplomat.

This is how the idea behind one of the rare successes of diplomacy in Ukraine was born in Geneva, at HD – the Black Sea grain initiative, which was concluded in 2022 under the aegis of the UN and Turkey and then abandoned by Moscow last summer. Meanwhile, the GCSP has kept channels of communication open by organising discreet meetings in Geneva between Russians and Ukrainians.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/sj. Adapted from French by Julia Bassam.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.