For ‘St Leonards meets The World’, curator Paul Carey-Kent – whose home town is St Leonards – has matched six artists based there with six UK-based artists who bring an international dimension. Pairings are founded on the idea that the works have enough in common that a conversation between them will prove interesting. It is to be celebrated that, despite Brexit and the way Britain is run, there are still plenty of artists from across the world who are based in the UK.

Featured artists: Hermione Allsopp, Blue Curry, Colin Booth, Koushna Navabi, Joe Packer, Robyn Litchfield, Toby Tatum, Tereza Bušková, Geraldine Swayne, Miho Sato, Alice Walter, Kristian Evju.

Hermione Allsopp and Blue Curry (originally from the Bahamas) are sculptors who exploit how found objects encode meaning, and here those meanings relate to the nature of tourism – in two rather different coastal locations. The installations of Colin Booth and Koushna Navabi (Iran) incorporate chairs – but neither sets them up for comfortable rest, so much as an anatomisation of the world’s problems. Joe Packer and Robyn Litchfield (New Zealand) are both atmospherically bosky painters who can be read in formal or environmental terms, yet their perspectives are not so similar.

Geraldine Swayne and Miho Sato (Japan) paint people – the former with highly diverse media and scale, the latter much more consistently – but both withhold enough to make the emotional tenor of their not-quite-portraits fascinatingly ambiguous. Toby Tatum and Tereza Bušková (Czech Republic) make films celebrating and elevating the everyday – in nature and in human tradition – to highlight its beauty and suggest an underlying significance. Alice Walter and Kristian Evju (Norway) both collage together disparate sources and materials to make paintings with mythic resonances, but there is – apparently – a sharp difference in the control they bring to those combinations.

Beyond those paired conversations, there are points of connection across the show as a whole. One might, for example, consider the unexpectedly rich and pointed implications the quotidian can have; the interface between ‘high’ and ‘low’ cultures, between tradition and modernity, between natural and constructed, between different nations; or the importance of materials – including the site- appropriate use of sand – all as St Leonards meets the world.

Hermione Allsopp makes sculptural work by turning found objects – frequently furniture – into new forms or compositions. These are familiar, known, domestic items that have been discarded in charity or junk shops – not, inert materials, but ones that carry collective attachments, memories and meanings. She sees that as ‘raising questions about the value and material nature of everyday objects’. That may turn a desirable item into something repulsive, or introduce questions of taste. ‘Sandhole’ uses an inflatable ring to reference the conventions of local tourism: holidaying, the beach, swimming, ice cream, sticky food – and the fact that we’re on the site of the impressive lido that stood in front of the gallery’s building from 1933-86. We might ask, though, what such rings are for: this one seems to have been rendered insufficiently buoyant to aid a swimmer or effect a rescue. It’s not much of a stretch to think of peril at sea, and then of small boats full of migrants…

Blue Curry grew up in The Bahamas – but came to the UK in 1997, aged 23. Since then he has been living a ‘life between islands’, bouncing back and forth, making work in both the UK and the Caribbean. He has spent time working throughout the islands and takes an interest in how the whole region is viewed and consumed. Utilising that background, he stacks up and compounds ideas of the exotic, the native and the tropical, facilitating their critical examination. He does that by combining found objects that speak of such issues. ‘Rent-a-dread’, for example, references the common occurrence in Caribbean tourism of mostly white Western tourists fulfilling certain fantasies by paying to be with a usually-dreadlocked Rastafarian-styled man to spend time with them on their vacation. The form matters, but – noting satisfying tourist expectations can be ‘like living in a deafening echo chamber of clichés and stereotypes’, Curry is interested in ‘the fantasy and the reality of the Caribbean, and how one replaces the other.’

Colin Booth combines, alters and re-contextualises found elements – of material, history and language – to form resonant new constellations of meaning. He moves things out of their utilitarian origins into a new being as objects of contemplation, and in so doing connects social and cultural aspects of past and present. His themes are often heavyweight – he has, for example, installed the shortest sentence in the Bible – ‘Jesus Wept’ – as an imposing neon sign in a socially disadvantaged neighbourhood, so relating an ancient phrase to modern conditions using current technology. Booth’s appealingly cheerful installation of sun-yellow chairs appears lighter in mood. But something is wrong with them: none is quite true, though each arrives slightly differently at its point of impending imbalance – like a comic version of one of Sol Lewitt’ s conceptual series of variations on a form. One imagines sitting and toppling. Would that be just to clown around, or is the world out of tilt? Matters could be serious, after all.

In 2022, Tehran-born Koushna Navabi founded the campaign ‘Artists for Women Life Freedom’, giving a clue to the political charge behind how her work explores the constant rub of the familiar and domestic against the surreal and the strange. She works in mixed media with a strong emphasis on textile, embroidery and knitting to present a variety of deformed, transformed and reformed objects: a female body, dismembered and rendered from rough wood fused with a rug from home; a ring for the finger, its intimacy disrupted by a tiny political monument. ‘Female Trait’ looks like two outsized ovaries on a pair of 1950’s school chairs, complete with fallopian tube and what might be hair sprouting from follicles seen through a microscope. It combines the bodily with a disruption of the sacred, for Navabi has cut into two Persian kilim carpets, which she says is ‘sacrilegious for an Iranian: however old they are, you are supposed to mend them’. The combination reads as a critique of the role of women being linked to reproduction, rather than education.

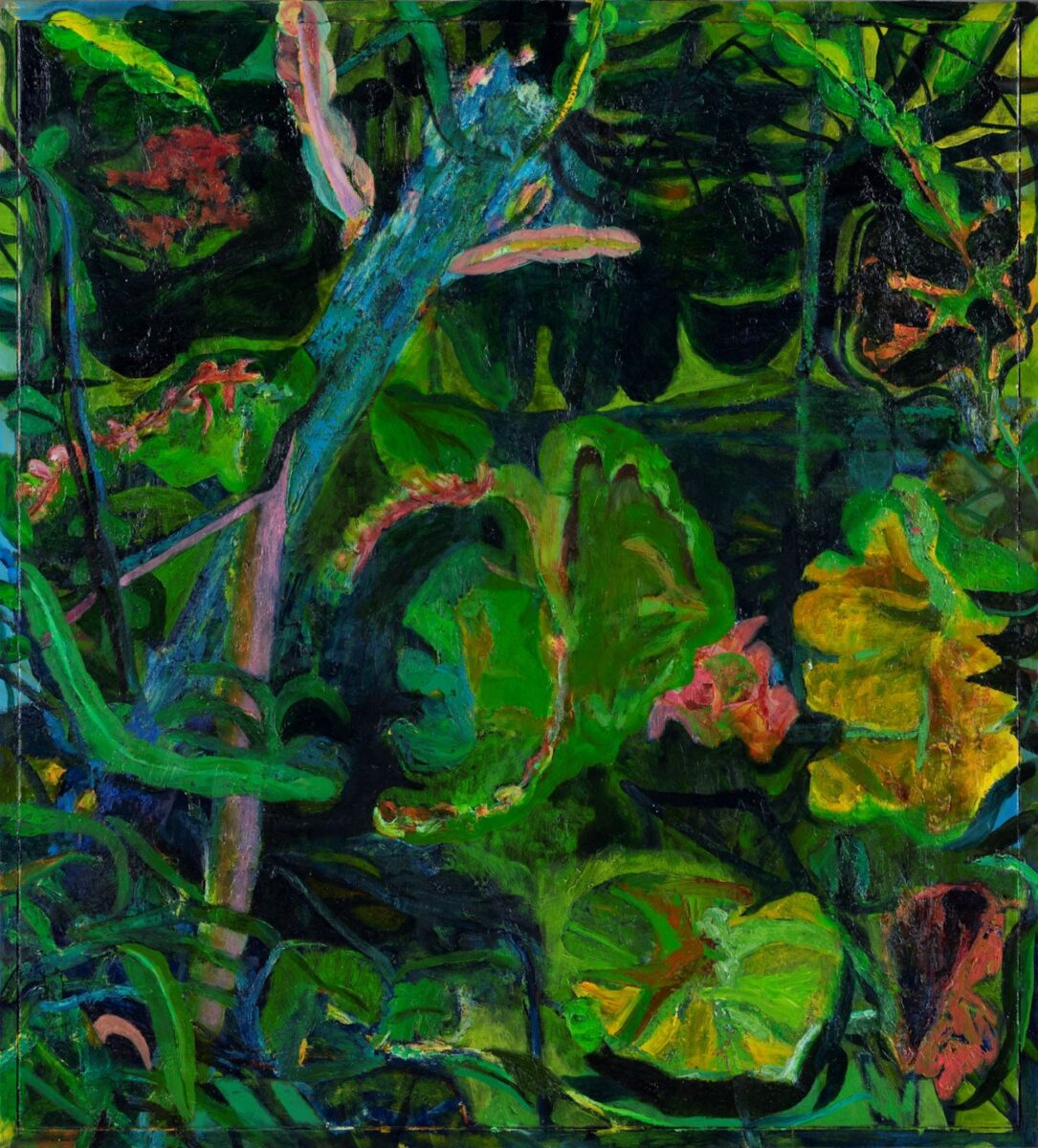

Joe Packer grew up close to English woodland, and this experience is part of what informs his current paintings. That said, his landscapes almost give way to abstraction – he describes the idea of painting landscape as ‘an armature to hang the painting on’ rather than the primary subject. His works are dense with form and colour, and rarely feature the horizon. Consequently, they feel closed-in and subterranean, and it’s hard to judge scale: are we in the microscopic undergrowth or looking down at the patterns of a forest? Is that a tree or a leaf? That generates an ambiguity, aided by his preference for framing the paintings internally as well as externally. As Packer explains: ‘I don’t like the abruptness of the edge whereby a painting ‘just stops’, so I often break up the edge with a frame which is part of the painting yet also ends it.’ The result is a psychologically charged space in which to engage with the visible drama of how a painting is made.

Robyn Litchfield returns regularly to the South Island of her native New Zealand to find the inspiration for her atmospheric forest landscapes. Originally, she used old photographs as a source, finding that she liked how their black and white framed the world and freed up colour for her own decision-making, allowing her to develop the landscape as a ‘psychologically transcendent space that produces heightened self-awareness’ and led to the somewhat other-worldly monochromatic aura of her interpretations. Much of the unspoiled, never-logged area is fertile swamp forest, so Litchfield has to travel by kayak to find the best views. Most of the trees are Kahikatea or White Pine which grow up to 65 metres high with a lifespan of 600 years. ‘You feel’, she says, ‘in the presence of beings’. Viewpoints are obscured much of the time, and Litchfield mimics that effect by using stencilled shapes as portals within the landscapes. Recently, she has floated those shapes free of the backdrop to float against swirling cloudiness, as in ‘Fragment 1’.

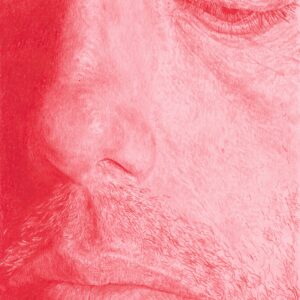

Geraldine Swayne has worked as a special effects designer and musician, and made experimental films… all of which one might trace into the lively vibe of her paintings. They range from miniatures on glass to sweeping larger-than-life acrylics, though various types of enamel on aluminium might be her most characteristic medium: that yields a ‘glassy surface’ she likes, allowing the effect of light coming through, of material revelation rather than mere image. Are they speaking of another place? Swayne’s sources are disparate – from her own photographs to found caches of vintage material to pornographic magazines – but the effect tends to be filmic, as if they are stills preceding an action, or there’s something going on off-screen. The subtext, then, may be narrative or revelatory: we are invited to speculate, but matters remain mysterious. Swayne’s apparently more straightforward pictures pick up some that charge from her wider practice. What is the text that Suzanne is reading? How come the simple act of plaiting seems to be leaking into the painting’s background? What has so drawn the smoker’s attention out of frame?

Miho Sato trained as a graphic designer in Japan, but has been painting in London for three decades. She hoards images – mostly of people – she finds in magazines, postcards, or reproductions of other artworks. So, popular culture meets the history of painting – but once something appeals to her, all is absorbed equally into her treatment. She reworks the sources in rapid and muted acrylic, simplifying them, freeing them from any specific setting, omitting shadows, hiding any facial detail – so denying

the viewer the usual point of engagement. The result is a curious combination of clarity and vagueness, as if her subjects are floating up from memory – an effect heightened when the subjects, as here, appear to be children. That yields a haunting resonance, but the emotional tenor is hard to pin down. Is ‘First Step’ a charming reminiscence of achievement, or is the inexperienced skater about to fall? Is the washing out of detail a means of focussing on the emotional core, or is Sato criticising anonymity and blankness in modern society?

Toby Tatum writes illuminatingly about his own films, so over to him on ‘The Garden’, 2019. It’s composed of ‘only two extended shots, both showing variations on a manufactured garden of outsized plants and rock formations, which are subject to a prismatic incursion of shimmering lights. The film’s title seems simply descriptive, and it does describe the film – the garden being a bordered, organised outdoors, set apart from the riotous, inhuman sprawl of nature – but it also brings to mind the Biblical garden, the prelapsarian space where the serpent lurked. Perhaps the first of the film’s two gardens might represent some sort of elevated spiritual realm whereas the succeeding space, emerging from the river of serpentine lights, suggests a more sensual realm, perhaps even a fallen world. At the time, I was making The Garden, I considered it representative of what I liked to call Psychedelic Romanticism… not only in its streams of colours, but also in its emphasising of flowers and plants and in the open-ended, ambient time-space that it occupies.’

Originally from Prague, Tereza Bušková came to my attention for short films made in Bohemia, presenting living tableaux – more like a linked succession of moving paintings than a story – in which traditional rituals are seamlessly merged with artistic reinterpretations and interventions with haunting, cello-heavy soundtracks. They can be taken to assert the resilience of rituals that outlasted communism. Bušková has recently made her films here, in collaboration with people. ‘The Little Queens’ is an ancient Moravian festival: on the cusp of spring and summer, rural communities used to celebrate their daughters in order to strengthen their own connection with nature and ensure a bountiful harvest. The people of West Bromwich revisited it for a 21st Century audience. ‘Surrounded by their attendants clad in festive raiments’, explains Bušková, ‘the King and the Queen walked under an ornate canopy and gave blessings to all… The ultimate creation was a richer, more cohesive community, one that can weather the relentless waves of anti-immigration sentiment, misogyny and xenophobia.

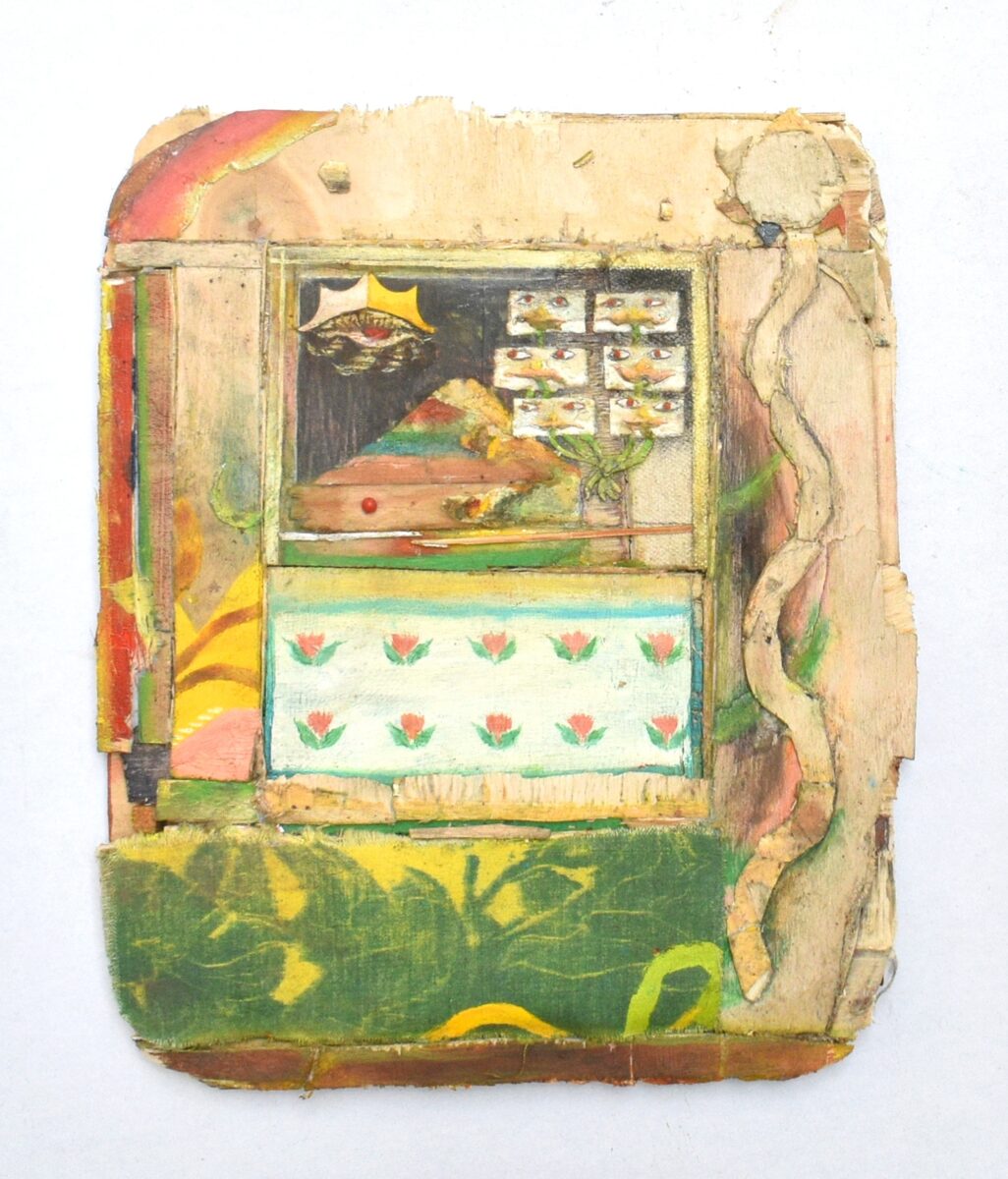

Alice Walter builds her endearingly ramshackle paintings from small sections of sawn plywood, frayed odds and ends of previously used canvases and oddments that have fed themselves from the locality into the decidedly functional mess of her St Leonards studio. If that sounds abstract, it is – until the textures and colours suggest some sort of figuration – then she goes with that, adding in some recurring tropes, such as a ‘blockhead’ that might be a self-portrait of sorts – she likes ‘the idea of the cartoon bringing things down to earth in a humorous way’. Out of all that something of the medieval, the folksy and the surreal coheres in a peculiarly Walterish way, topped off by riddling titles. Where is the sunflower in ‘Demise of Sunflower’? Ah, of course… Then we go back and forth between the material reality, the ambiguous space and scale, and the compelling presence of her small worlds.

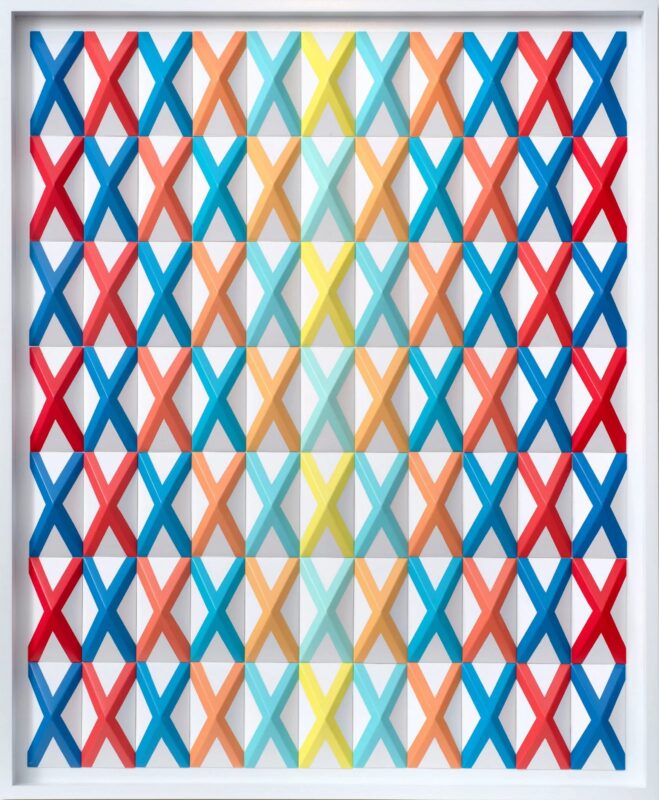

Kristian Evju tends towards the enigmatic. His characters – whether in a play or dream – are a mixed bunch, but then Evju explains that he ‘doesn’t want to know anything about’ the figures he draws from a vast range of historical archives. ‘I look at paintings like arguments about whatever I’m trying to explore’, says Evju, ‘but who knows what that is?’ Scenes and characters are inspired by found imagery, fragments of the past merged with an imaginary present. Moreover, he adds in equally mysterious patterns, such as the op-art styled bodies in the ‘Interventions’ series, and often places the figures in geometrically and materially elaborate settings – here a geometric structure of poplar, aluminium and Perspex. Yet what sounds as if it will jar is executed with manic precision, so that the implausible becomes illogically convincing. Yet that still leaves us unsure of time, place or the degree of reality – and of the mood: are these surreal japes, or dystopic dissections of the post-truth world?

Curated by Paul Carey-Kent

ST LEONARDS MEETS THE WORLD, 17th-27th May 2024, Electro Studios, St Leonards-on-Sea, East Sussex.