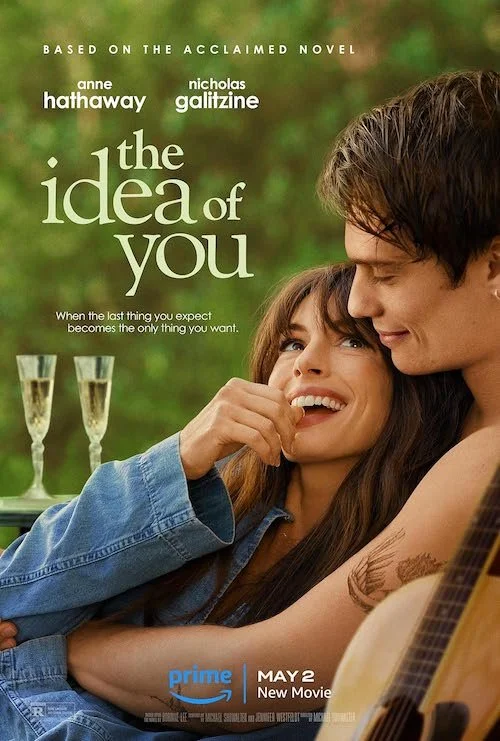

The Idea of You

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: the following review has spoilers for The Idea of You. Reader discretion is advised.

A couple of years ago showed actor-turned-director Michael Showalter losing grasp of what makes a motion picture feel complete with the biopic The Eyes of Tammy Faye, which felt like an anomaly at the time of its release. Perhaps a project this audacious for him was too big to the point of him losing his bearings. I considered it a one-off event for him because of how solid his career has felt before this point. Additionally, his latest film (I never got around to his 2022 film, Spoiler Alert), 2024’s The Idea of You, was a return to the romantic dramedy, something he’s nailed before with what I consider to be far and away his best film (The Big Sick); to be fair, he also now has this fuck-you budget that he scored once Tammy Faye earned star Jessica Chastain her first Academy Award (and the film won an additional Oscar for its makeup and hairstyling), so maybe The Idea of You would be even more fully realized. That is not the case. While the film is great at nailing what the butterflies feel like when one is in love, it is sadly in the name of the feature: it’s merely the idea of what actual adoration feels like.

It cuts to the chase with art gallery owner Solène (Anne Hathaway with a terrific performance, albeit one that is given a wonky set of objectives that never properly allow the star to get as far as she could), who is recently divorced and has the last minute responsibility of taking daughter Izzy (Ella Rubin) and her friends to Coachella, including a meet-and-greet with boy band August Moon. Solène is out of her element here and quickly finds herself lost when trying to go to the bathroom, winding up in the trailer of August Moon heartthrob Hayes (Nicholas Galitzine) by accident. Of course, because The Idea of You is more interested in these two as a romantic pair than anything else, Hayes begins hitting on Solène instantly, with the latter playing hard-to-get (to be fair, she may actually not be interested, considering that she is about to hit forty and Hayes is a child in comparison). Once Hayes dedicates a song to Solène, who is in the audience of the evening set with her daughter, that’s it for the aimless gallery owner: she finds solace in the music of a group that even her child thinks is beneath her (or so she says). From this point on, The Idea of You does a fairly great job of making the romantic connection between both Solène and Hayes feel legitimate, with some steamier sex scenes than you’d imagine for a mainstream rom-com-dram of this nature, proper chemistry from Hathaway and Galitzine (the latter who holds his own quite nicely), and the turning of each blissful sequence into a music video (of sorts); these are the moments where The Idea of You shines.

The Idea of You understands what love feels like but not the many steps necessary in order for true love to take place.

Where The Idea of You stumbles tremendously is with its pacing and circular narrative; considering that this is a two-hour affair when it could have easily been a streamlined eighty minutes, that’s not a good sign. Solène and Hayes break up or go on a break enough times for us to not really care whatsoever what transpires, which is precisely what you don’t want in a romantic film. What’s even worse is the formula which is the exact same almost every single instance: Hayes initiates contact, Solène feels like this won’t work out, and a separation ensues. This was true for how they met, and for most of the arguments afterward (Solène begins the confrontation, Hayes fights to keep them together, Solène relents, Hayes respects her wishes for a minute, then either Hayes or Solène, the latter like once, will be the first to reach out to make up, and we’re back to square one). This becomes a farce once they fight yet again (for quite a legitimate reason: this relationship is proving to be detrimental to Izzy’s wellbeing with the bullying and harassment that Solène and her family are experiencing). Solène and Hayes make up very quickly (minutes later, judging by the runtime of the film) for a quicky (yes, for sex), and Solène calls off the relationship again. Couldn’t they have just called it quits after the intimate moment?

This is a minuscule example of the overall problem of the film: it has no concept as to why or how a climactic scene works. It’s basic writing 101 that you progressively build towards a moment in order for it to carry weight, feel special, and prove its importance. Using another recent romantic film for a comparison, you see Sutter throw himself away in The Spectacular Now and come to his senses, rushing to try and save the biggest mistake of his teenage life. You understand his self-destruction after some gradual storytelling, and you feel his urgency to rectify his relationship. The Idea of You has its two leads separating — with very little friction or rawness I might add — so frequently that it feels like old business by even the second time this happens. There’s no building towards anything. This Jenga tower keeps getting toppled over whenever it reaches its fourth row, so by the time the film ends, we’re left with a three-block-high tower that possesses the fortitude of a child burping his alphabet. So what? I bring up The Spectacular Now because both this film and The Idea of You leave you with an open-ended final shot that is meant to leave you wondering about the future of these two people as lovers. With The Spectacular Now, you’re fighting off a rush of questions and realizations. With The Idea of You, I personally sat back and said to myself “here we go again; I give them two in-film moments” before they were spared with the credits sequence.

What do these characters learn? What advancements do they take as people? I feel this film quite strongly which is its only saving grace (it’s quite difficult for a film to have you experiencing romantic emotions this strong, so at least you know the film is doing something right occasionally), but I also cannot fathom what this film is trying to say. What comes from this May-December relationship (no, not that one) that we can take away as a new angle on the older-younger pairing and its taboos and values, outside of how it appears as a fantasy or fetish? The Idea of You gets so caught up in trying to get you to feel what its protagonists are feeling that it completely loses grasp of why they’re feeling this way. If you look at some other recent romantic films like Call Me By Your Name or Portrait of a Lady on Fire — ones that actually focus on their characters, histories, and settings to the point that they’re longing for the romance that their respective films promise, you’ll understand what I mean about building towards these emotional payoffs. Hell, you don’t even need to go that far. Just look at Showalter’s best film, The Big Sick, which is hinged by one — count it: one — key breakup sequence and the crux of the story that follows after (and the rebuilding that takes place in numerous ways). The Idea of You feels like a missed mark by a director who once knew what it was; it plays like a midlife crisis-laden soul who peaked in high school and cannot stop relishing in the memories of his high school sweetheart. This isn’t true love: it’s called being in love with the concept of love.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.