This is the second installment of the 2024 edition of the French Dispatches, our on-the-ground coverage of the Cannes Film Festival.

In 1924, René Clair, a French filmmaker associated with the Surrealists, made an hourlong film called Paris qui dort, or “Paris Asleep,” in which a mad scientist creates a ray gun that freezes everyone in the city exactly in place. At first, only the night watchman of the Eiffel Tower, high above the city, is untouched, and he comes down to street level to explore and play in the suspended city, where each citizen-extra is frozen in place, arrested mid-movement. Using early special-effects techniques — slow- and fast-motion, running the film backwards, freeze-frames — the film encapsulates the basic premise of moving pictures, that is, to manipulate time. A mix of frothy comedy and futurist wonder, the film is imbued with the optimism of the 1920s, a time of modernity’s rapid remaking of the urban landscape, and of the rapid evolution of the technology of filmmaking itself.

Megalopolis, which had its world premiere yesterday at Cannes, begins with a mad scientist played by Adam Driver perched on the roof of the Chrysler Building. Peering out over the streets below, he commands: “Time: stop!” And the greenscreen clouds above stop moving through the sky, the greenscreen cars below stop moving through the streets. One hundred years after Paris qui dort, Francis Ford Coppola’s film takes up anew the promises of technology, the possibilities of the city, the potential of the cinematic form. Everything that everyone has already said about Megalopolis in the 24 hours since its premiere, positive and negative,is true: it’s overambitious, undercooked, baffling, dubious, sentimental, messy, innovative, startlingly beautiful, profoundly moving. The 85-year-old Coppola has more than delivered on his ambition, nurtured for half his life, to make a film that encapsulates all his biggest, most contradictory ideas about… well, the future of art — nay, of humanity itself. And I laughed a lot during the movie — with it and at it, with pleasure and disbelief and gratitude. It’s philosopher-king shit.

Driver plays Caesar Catalina, a Robert Moses–like urban planner in “New Rome,” which is New York City but largely shot in Atlanta and in front of greenscreens; the city is crumbling and going bankrupt, with “Feds to City: Drop Dead” headlines — one of many instances in the film of exposition-by-newspaper — recalling the 1970s era of urban decline that was also Coppola and the New Hollywood’s filmmaking heyday. Another retro callback comes in the form of the discotheque, full of cocaine and rollerskates and topless women, where the mayor’s daughter Julia (Nathalie Emmanuel) parties with the children of banker and kingmaker Crassus (Jon Voight), including Shia LaBeouf as an incestuous and intermittently cross-dressing schemer straight out of Tinto Brass and Bob Guccione’s Caligula. The names (like the hairstyles) come from the Roman Republic, in the tumultuous decades before the rise of Empire and imperial heyday; so does the name of Catalina’s historical rival, Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito), here the mayor of New Rome, who, much like the current mayor of New York, sucks and is roundly booed whenever he shows his face in public.

Revisiting “One From the Heart,” the Film That Almost Bankrupted Francis Ford Coppola, 40 Years Later

The movie turned the beloved director into a Hollywood outsiderCatalina and Cicero’s rivalry is over the future of New Rome: Catalina, the Nobel Prize–winning inventor of a miracle substance called “Megalon,” dreams of remaking the failing city as a “Megalopolis,” which, when envisioned by Coppola and his overworked computer artisans in smeary golden-hued renderings of eco-adaptive buildings and people-movers, seems something like a solarpunk 15-minute Tomorrowland.

Driver is an actor who can convincingly play both goofiness and irrational anger, like a child but bigger. In Catalina’s lab, especially, the playful side of his performance comes out; like Jeff Bridges, as the titular maverick automaker in Coppola’s crypto-autobiographical biopic Tucker: The Man and His Dream, Driver conveys his character’s energy, his enthusiasm, his winning stubbornness and capability to inspire loyalty — he’s a why-not futurist fighting the pragmatic naysayer bureaucrats, and also like Tucker a portrait of the artist as emotionally volatile and demanding. Like Coppola, Catalina is a grieving widower: Coppola’s wife Eleanor, who directed the immortal making-of documentary Hearts of Darkness, about the Apocalypse Now shoot, and weathered the operatic highs and lows of her husband’s career and psyche, was ill during the Megalopolis shoot, and died shortly after its completion; Catalina’s wife Sunny Hope (the most on-the-nose of the film’s many nostril-bothering character names) died under mysterious circumstance, driven toward the grave, Catalina believes, by “my moods, my mania.”

Catalina is “a man of the future so possessed by the past,” as Julia, who comes to love him, observes. (Emmanuel is quite good in the film, carrying off with poise the role of an adoring helpmeet with some unwieldy dialogue, giving Julia an elegant guilelessness.) This dual view, nostalgic and vanguard, applies to the film itself; as Catalina’s plans for Megalopolis, a city to reinvent civilization, are a synecdoche for human potential itself, which is also how Coppola sees filmmaking. Given his difficulty in making the film — he financed the film with $120 million of his own money, financed by the sale of his vineyards, because no studio would take a chance on it — he likely sees cinema at risk of decline, which is also where New Rome finds itself. LaBeouf’s Clodio becomes a Trump figure, a faux-populist demagogue whose admirers call him “an entertainer” and says things like “Don’t tread on me.” (He also creates some fake news, in a dubious subplot in which a prominent man is unfairly MeToo’d.) The dialogue and iconography is not subtle, nor is the metaphor of an impending apocalyptic disaster threatening New Rome. (Though Coppola did considerable work on the project around 9/11, which shows, it now plays equally well for climate change.)

As Catalina imagines a utopia rising out of the ashes, grieving the past but hoping for the future, for humanity and for cinema, so does Coppola. There’s a startling moment of rupture in the film, one that created a frantic buzz of confusion and anticipation among the experienced moviegoers in the Debussy, a shock-and-awe gesture that hearkens back to silent-film exhibition practices (as well as William Castle gimmicks and more recent experimental “expanded cinema” performances). It’s probably impossible to recreate on a large scale, but it suggests Coppola reinventing cinema by going back to square one. Megalopolis is seen first in sketches, storyboards, concept art, visions from the history of previsualization, and Megalopolis is assembled from a jumble of classic practical and new-school techniques, sometimes juxtaposed to each other to surprising effect, sometimes synthesized: iris effects, flashbulb montages, shadow-puppets, split-screen, superimpositions and psychedelic abstract visualizations, airbrush-slick CGI cityscapes conjuring Trapper Keeper illustrations and Art Deco pastiches. It’s hectic, overabundant, luxuriant and disorienting; as in Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the visual range of the film spans the prehistory and history of moving-picture technology (the name of Coppola’s production company, American Zoetrope, nods to a forerunner of cinema) to tell the story of a lonely man beating back the currents of time.

(Also like on Dracula, Coppola fired much of his VFX team mid-production, and relied heavily on his son Roman to devise effects. This is very much a family affair: Coppola’s sister Talia Shire shows up to riff on string theory as Driver’s overbearing mother, and her son Jason Schwartzman shows up to play the drums; there are brief roles for one of Sofia Coppola’s teenage daughters, and Balthazar Getty, whose family dynasty is connected to the Coppolas through ties more complicated than I have time to explain right now. There are also plum roles for LaBeouf and Dustin Hoffman, both accused of abuse and harassment by multiple women; both are excellent, and the casting of both feels distractingly pointed.)

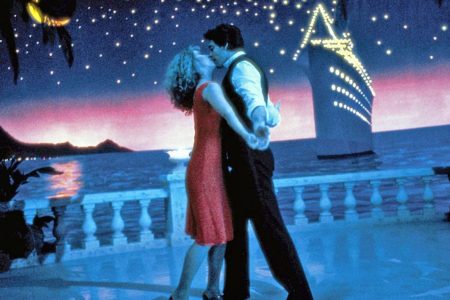

Whatever politics Megalopolis and Catalina espouse, about debt or Wall Street or universal human dignity, this is a Great Man view of history (and a Supportive Woman view of romantic relationships). This is not the first time Coppola has risked it all to push the medium forward, and as in his most beautiful film and greatest financial failure One from the Heart there are coups de cinema here to take your breath away: I was stunned by a sequence demonstrating the impending collapse of New Rome in which the city’s public neoclassical statues, robed figures representing ideals like Justice, are depicted as living beings, sighing and sobbing and collapsing in despair. In New York, Bilge Ebiri writes that “at one point, Adam Driver does the entire ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy from Hamlet. Why? I’m not exactly sure.” But to me the answer is obvious: Coppola didn’t want to die without tackling Hamlet. He tackles everything else.

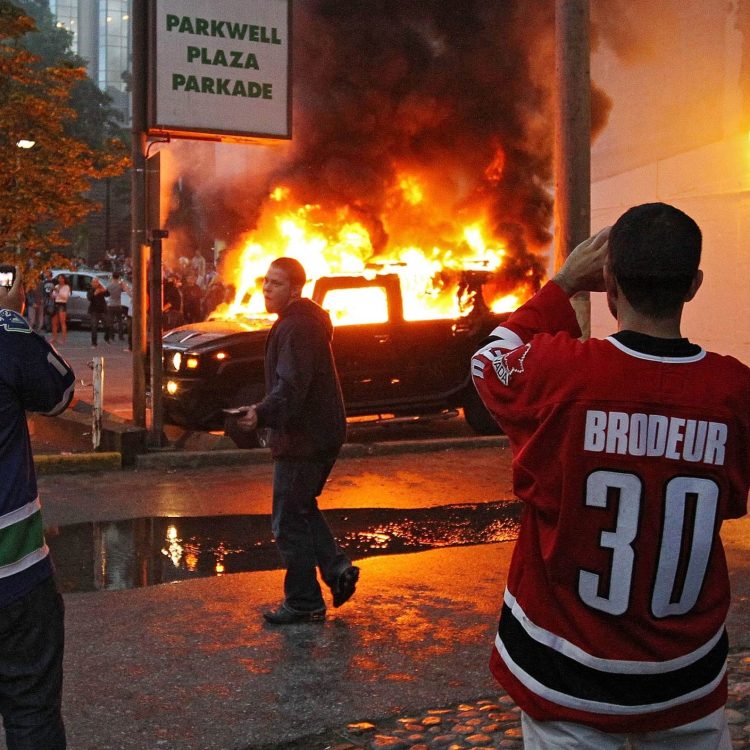

Megalopolis is not afraid to be cringe, in ways that only the young and passionate and old and wistful can be. “But what is time,” ponders a speechifying Catalina in one scene — dude, I know, right? The dialogue is undigested quotation and inspirational sloganeering; the humor is raunchy — the film also betrays its 2000s drafts with an extended riff on the virgin Britney and the dirrty Xtina; the politics are underbaked, the sentiment is teary, and the children are our future. Big setpieces, like a vast Circus Maximus in Madison Square Garden, are cartoonish and underresourced, to an extent that underlines the overreach of style, philosophy and politics, to say nothing of the often glitchy plotting. Treated with a glistening digital patina and met at my press screening by a smattering of boos, it may be the hottest mess to hit the Croisette since Southland Tales, a film it very much resembles, down to a hysterically vampy Aubrey Plaza channeling Krysta Now as the power-mad, nymphomaniacal TV financial journalist (“money bunny”) Wow Platinum, who serves a similar function in the narrative as Agrippina in I, Claudius.

Is the film as unreleasable as Hollywood’s risk-averse, Cicero-like executives declared it to be after its first preview screening? Paradoxically, early critical naysaying (or awed befuddlement) at Coppola’s disasterpiece may make it a marginally more commercial proposition. You have to see Megalopolis — and Megalopolis — to believe it. Or is it: you have to believe it to see it?

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.