The Hypnagogic, Primordial Ooze of Jessica Pratt’s Old Hollywood

After releasing one of the very best records of 2024 so far, we caught up with the California singer-songwriter about how the Manson Family, the Beach Boys, the instrument of a recording studio, and natural, oceanside wonders influenced Here in the Pitch in our latest Digital Cover Story.

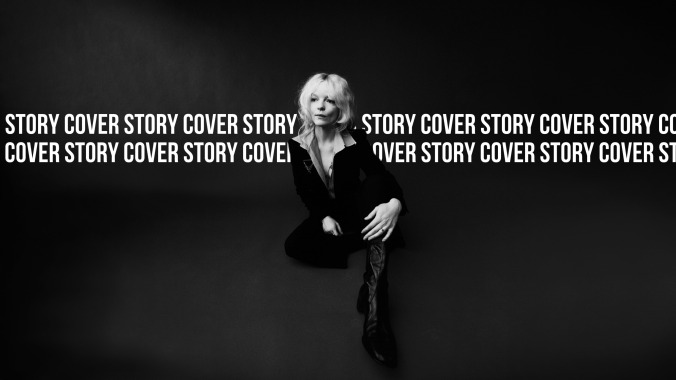

Photo by Samuel Hess Music Features Jessica Pratt

“Here in the pitch-dark atmosphere above, the trembling of the apple and the yew, here on the anniversary of their death,” William Butler Yeats once wrote in “Supernatural Songs.” “The anniversary of their first embrace, those lovers, purified by tragedy, hurry into each other’s arms.” Jessica Pratt didn’t title her newest album, Here in the Pitch, after the Irishman’s century-old line. It’s far more of a coincidence, better related to the mineral tar or bitumen derived from petroleum. “Sometimes you think you’re coming up with a novel combination of words, but the English language has been happening for a long time,” Pratt says. “I do like those serendipitous connections, though, because then the connection is made—whether you want it to be or not.”

Pratt, when she isn’t writing music, works on poetry in her spare time—though she’s never put any of her work out for the public to consume. The 37-year-old sees the medium, however, as a way of opening her own writing process up—as a way of walking out of the “phonetic prison” she gets locked in while chipping away at lyrics. Here in the Pitch comes from a poem of hers with the same title, which she wrote around the same time she was making the record. For Pratt, poetry and music co-exist side-by-side, sometimes influencing each other but not always. “It works in this way where, for me, anything that sounds ominously profound is usually something that just emerged from my subconscious without any real or deep examination,” she says. “I like ‘pitch’ as an allusion to darkness and the primordial ooze aspect of pitch and tar coming from the center of the Earth. In this very primal way, it’s very elemental. I felt like there was a lot of that energy on the record, so it seems to fit for me. I like titles that are a bit ambiguous.”

This month, Jessica Pratt released Here in the Pitch to widespread critical reverence (it’s currently the ninth-highest rated album of 2024 thus far on Album of the Year). Pitchfork awarded it a coveted Best New Music, and it’s currently tied for their second-highest rating of the year, below Cindy Lee’s Diamond Jubilee (“I’m a huge Cindy Lee head, what can you say?” Pratt mentions at one point in our conversation). I reviewed the record for Paste and gave it a 9.5 out of 10, which is also our second-highest rating of the year. It’s not often that I get to review an album and then write a cover story on the artist who made it (the only previous instance was in 2023, with Geese). I wasn’t even going to review Here in the Pitch at all, to be quite honest, originally wanting a freelancer to reckon with it after my cover story made it onto the schedule. But as release day grew closer, it became obvious to me that Here in the Pitch is a record that demands an affectionate eye—it’s the kind of LP that, truly, only arrives to us once in a great while.

Perhaps you are drawn to Here in the Pitch for similar reasons—for Pratt’s ageless ingenue, or her ability to make modernity sound so damn heady. The nine songs that make up her fourth album tend to simmer, never climaxing into some larger-than-life climax or euphoric finale. Instead, they rest in the meters of pop excellence, forgoing any urges to sprawl. “Life Is” is one of the year’s best opening songs, and “The Last Year” is one of its best closing songs. Between those bookends, Pratt puts solemn grandeur to good use. The music effervesces yet rattles with weightless menace; existing as a kind of hypnagogic folk prospering that flirts with sophistication yet drops out into an avalanche of brightly lit doom. “I never was what they called me in the dark,” she sings at one point. “I never was, here I sit so long.” With a 12-year catalog as bulletproof as it is short, Pratt has found the old “they don’t make them like they used to” saying as a challenge worth taking.

Here in the Pitch, like its predecessor Quiet Signs, was recorded in a professional studio: Gary’s Electric in Brooklyn. After having made most of her sophomore album, On Your Own Love Again, in her bedroom in Los Angeles, she welcomed the opportunity to sit with her songs longer, rather than just writing and recording one all in a matter of hours, like she’d done on her first two LPs. Her approach to building albums, whether she was at home or in a recording booth, remained largely unchanged—though, she acknowledges that the studio is good for wanting to do more elevated work that isn’t just flexing the “whatever I have around will do” muscle. “At home, there are so many variables that can change the sound of what you’re doing,” Pratt says. “If you’re recording in a small room with a microphone, that’s kind of it—aside from the post-production stuff you can do. You can move to various rooms with different sounds but, in general, you’re gonna get one sort of thing. It’s fairly limited in a way that I think is useful, actually.”

“I think when recording in a studio, if you’re going into a process of creating arrangements for a song and daydreaming about various overdubs that could exist, there’s more of a delay between the laying of the foundational tracks—the vocal and the guitar—and the stuff that comes later,” she continues. “Whereas, previously at home, I would write a song and record it all in one day, and then it would just be done. You sit with songs for longer, which I think can be both good and bad. If you write and record a song in one day, there’s not really a lot of time to let things percolate. And you might miss out on stuff. But it has this primitive quality that’s difficult to get in the studio sometimes.”

Pratt has said it herself that getting the right feeling when she is writing and recording music can take a long time to do—hence why five years passed before she put out her Quiet Signs follow-up. Whatever feeling she was chasing this time around, it’s nearly impossible to decipher. Instead, there’s a lot of trial-and-error; some songs that work on paper never come to fruition in the studio; roads are explored but conclude with dead-ends. “You can listen to [Here in the Pitch] a few times and probably draw conclusions that would be fairly correct,” Pratt says. “The feel and mood of the record and the thing I’m searching for is dictated by the music itself. It becomes this somewhat frustrating divination process, where I know that there’s a correct path but I don’t necessarily know how to fully identify it. It’s song by song, following this invisible thread.”

No stones were left unturned once Pratt finished making Quiet Signs, and it and Here in the Pitch now exist as time capsules of where and who Pratt was when she made them—and, in her own words, “the songs happened the way that they were supposed to happen.” “Unless you’ve really lost the plot,” she continues. “I am okay with everything that has happened.” This time around, Pratt was joyful about bringing in different sounds, like bossa nova, folk-pop and baroque music, into the studio—because the songs she’d come up with were finally appropriate canvases for this chapter in her songwriting.

Pratt moved to Los Angeles while she was writing On Your Own Love Again 10 years ago, though she was still running on the fumes of her native San Francisco—which is why songs from that record sometimes sound as murky and foggy as the Bay Area. “As soon as I got to LA, I felt like I had moved to the country or something, coming from San Francisco—where everybody’s on top of you, you can never really feel totally alone, which sometimes can be a feeling that you like,” she says. “There’s not a lot of mental quiet there. If you want to be around people, all you have to do is step out your door. It has a small town feel to it, at least the time that I lived there. I had a lot of friends and I felt like I was constantly around people. So I think, as a result, I didn’t work on music as much as I could have.” By the time she was settled into Los Angeles, Pratt didn’t have many friends, didn’t know how to drive yet and wasn’t sure where she could go. She used the “mental quiet” of the city to put more focus on her music than ever before. “I think I started making music in a ‘real way,’” she admits. “It’s a place that is an interesting combination—there’s a certain amount of psychic activity, and I think any place that is near the feels charged energetically, as weird as that sounds.”

Pratt has a documented love for Musso & Frank, but the parts of her hometown that look like the music she’s making are much closer tied to the ecology and natural beyond than any familiar landmarks that might show up as set dressings in films. “The natural world surrounding LA, even the desert outskirts—I think about a lot about that, the combination of those two things,” she says. “The greener, wilder parts of LA and then the fringes, where things feel a little more thirsty and barren—I look out my window at that terrain every day. There’s a very earthbound, solid quality to some of the music on the record—more so than anything I’ve done previously.” During the first year of COVID, Pratt found herself traveling from Los Angeles to Las Vegas often to see her father, and her time spent driving through Death Valley exists in the same psychic categorization she gives to Here in the Pitch. Like Joshua Tree, too, the outskirts of Los Angeles are grimy and raw. “It’s been interesting to see, despite the attempts of gentrification, the seedy element cannot be banished,” Pratt adds. “The elements won’t allow it. Reality drops out because it’s just completely dead air.”

I tell Pratt at the height of her call that Here in the Pitch is an album that exists exactly for someone like me—someone who is deeply fascinated by the underbellies of Southern California, by the mythology of a city ravaged by serial killers, drugs, more musical and social movements than anyone could count and a never-healing source of unrest. If I could live inside the lyrics of “Glamour Profession” by Steely Dan, I would, I tell her. The neon depths and backlit trenches of Los Angeles are not so immediately recognizable on Here in the Pitch. They are emotional checkpoints delivered through sound and color, not through story. In music and in literature and in film, the West Coast has existed as a melting pot of unmistakable chaos in cultural history. During COVID, Pratt found herself immersed in the world of an unlikely cast of characters: the Manson Family. “In the depths of the pandemic, I think I was looking for some sort of mental stimulation, in a very straightforward way,” Pratt says. “I was reading a lot, and it was really nice to have the time to just completely be immersed in reading book after book without a lot of interruptions or work that was taking me anywhere. I read Helter Skelter by Vincent Bugliosi.”

Pratt didn’t have any pre-existing interest in the Manson Family. She’d been reading a lot of Stephen King novels and listening to the Caretaker’s Selected Memories from the Haunted Ballroom, a hauntological masterpiece that samples and manipulates various big band records to sound like the musical elements from Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of King’s The Shining—which inspired Pratt to read King’s novel in the first place, and led to a friend recommending Helter Skelter. “I got really absorbed by the story, the way that it relates to Los Angeles’ history and this cross-pollination with the music scene and celebrities is very interesting,” she says. But Pratt isn’t defending the true crime genre anytime soon. “True crime is getting a bad rap these days, and probably for good reason—so I don’t want to go too far down that road. Also, I think it can, maybe, fuck your mind up a little bit,” she adds.

After downing Helter Skelter, Pratt turned to Tom O’Neill’s polarizing CHAOS (“I was almost scared off because people were not kind to it in reviews. I think he was treated like a complete crackpot—which, maybe he is,” Pratt says) and Ed Sanders’ The Family (“It’s a tome, and it feels like reading an anthology of Greek myths,” she mentions. “You don’t know what parts of it are in any way reliable, but it’s interesting nonetheless”). Any rumor, story or tangential connection to the Manson Family, Pratt knows about it. And, while sitting in her home where, out of her window she can see the San Gabriel Mountains and Glendale, the California terrain coalesced with a bubbling, violent history in her creative brain. “I get very obsessed with various subjects and it colors my perception of my reality for a while,” Pratt laughs. “I don’t think I’m alone in that; there are a lot of people that do that. It’s like insulation against the world.”

On Here in the Pitch, Pratt beckons the scandalous energies of Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon and Tinseltown denizens in her songs—leading to hues of characters both autobiographical and fictional, both grimacing and familiar. The lines blur in her work and parallel the West Coast mysticisms of her home. “The natural beauty and the proximity to the water—it feels like the Wild West, or something,” Pratt says. “ Compared to the history of the East Coast—which feels like, for the United States’ standards, as old as it gets—there’s something wild and enchanting about it. It’s something that you can’t necessarily put your finger on.” There is something to be said about how the monolithic popularity of the Beach Boys, the Manson Murders, the New Hollywood era of film and, even, the Zodiac Killer headlines all collided at the same time. Like New York City, it’s a cultural epicenter where unbelievable things are interwoven and happening simultaneously—though Southern California, according to Pratt, “is a little freer and more open.” “Or, at least that’s the association,” she adds, chuckling. “I think it’s a little inexplicable.”

The shadow of Los Angeles arches over Here in the Pitch from the jump, as the record begins with Alex Goldberg playing drums like Hal Blaine. The percussion arrangement on “Life Is” conjures vestiges of Blaine tapping a Sparklett water jug during the sessions for the Beach Boys’ “Caroline, No”; the sounds of the Wrecking Crew and those ornate, Spector-era sonics exist in Jessica Pratt’s world, too. Pull back the curtain on any pop musician’s oeuvre from the last 50-some years and you’ll see just how present the Beach Boys’ revolutions are. You can hear them on “Better Hate,” the first song Pratt and her band recorded, which comes out the gate with echoes of timpani and baritone saxophone, parading Brian Wilson-esque vocal movements and LBJ-era sunshine pop relics. Before moving to Los Angeles, Pratt listened to Van Dyke Parks’ Song Cycle often and found herself really infatuated with the city’s mysticism—but she never intended to draw from that part of its musical history when she began making Here in the Pitch.

“Most of the creative process, for me, is feeling around in the dark and, if something is pulling you in a certain direction, you just follow that. Then, if it starts to feel correct, you just build on that,” Pratt says. “I think being in the studio environment, you are aware of the studio as a potential instrument. I had started to write songs that felt a bit more open and rhythmic in a way that, perhaps, called for outside color to certain instruments. On [Quiet Signs], there’s accents in some songs. It’s not completely barren, but it felt like the songs weren’t really asking for much. For whatever reason, there was a bit of a turnaround and the songs on Here in the Pitch have a sunny feeling to them. Maybe this is open to interpretation for other people but, to me, it feels like a bit of an underlying sinister quality in a lot of the songs on the record.”

Pratt has cited Pet Sounds as her “North Star” when making Here in the Pitch, and while it’s easy to contend that she, like Brian Wilson, understands how to make the walls of a studio its own character in the band ensemble, there are similarities in the lyricism, too—especially in how a grandiose, affluent instrumentation is working in such intimate and juxtaposed tandem with oft-devastating lyricism. I mention how something like “Don’t Worry Baby,” with its blissful hums that co-exist with tinges of sadness (“Baby, when you race today, just take along my love with you”), is more straightforward than something like “World on a String,” which wears post-psychedelia on its sleeve with open-ended verses and ashy, symbolic hues. “You should know the courage of my heart,” she sings. “Don’t suppose the earth could spin apart?”

“It’s a combination of an incongruent feeling with the sound of the music and the sound of the words,” Pratt says. “There’s a bit of a conflict there, where, maybe, the words are heavier than they seem. It’s that weird thing where it’s like, ‘Okay, in one verse [Brian Wilson is] singing about a car. In another verse, he’s laying down these fundamental truths about love and connection and loss.’ I feel like most art that we respond to, emotionally, has to have an unspoken element. Explaining everything all the way, especially with lyrics—there’re some people that can do very sober, open lyrics that tell you the whole story and nothing’s missing very well. I’ve always been intrigued by the shadowier elements alluding to something without necessarily explaining the whole story. If we were talking about The Shining, that was Kubrick’s bag, too. It feels more impactful if you don’t fully understand what’s happening but your mind can fill in the gaps.”

The Beach Boys’ 1968 LP Friends is a massive tome for Pratt, who wound up making “By Hook or By Crook” because she was attempting to learn how to play “Busy Doin’ Nothin’” on guitar and started fooling around with the main chords until a Jessica Pratt-shaped melody originated. “By Hook or By Crook” is a standout musical moment on Here in the Pitch, largely for its samba and bossa nova instrumentation. If you’ve ever watched a B-movie from the 1960s or ‘70s and it featured a lounge scene, Pratt’s wondrous, folkloric pop beat will be immediately familiar (the Dean Martin-starring The Wrecking Crew comes to mind quickly for me). Pratt was listening to a lot of Steve Kuhn, Burt Bacharach and Wendy and Bonnie while making Here in the Pitch, and their jazz singer origins converge with her affinity for the lore of pop music. It’s all elemental, and the tiki bar-primed songs in Pratt’s catalog exist because her curiosities wander towards vocal melodies present in the world of mid-century muzak.

A big part of Here in the Pitch I’ve latched onto is just how inspired by the forgotten girl groups of the 1960s it is. There are reflections of that lore in the sun-faded, nylon-ensconced, syrupy stupors of “Better Hate” and “The Last Year,” with Pratt’s childlike lilt of a potent but forgotten yesteryear anchoring each song’s emotional threshold. As the first vantages of Here in the Pitch make themselves known, spiritual remnants of the Murmaids, the Shaggs and the Tammys buoy to the surface—albeit slowed down and the dynamics now lacquered in cozy beams of hi-fi phonics. Pratt herself is a GTOs historian and a self-proclaimed Frank Zappa head who adores the analog tonalities of that era that can’t ever be faithfully reproduced. She likens Zappa’s mission statement of oddball cultivation to that of Andy Warhol’s, centering both auteurs as hosting “dual-coastal historical events.”

“Truly freaky sounds and a completely organic weirdness that was documented by somebody who was a professional archivist for that sort of thing—just weird people being themselves, capturing their dialogue, encouraging them to write these weird songs,” Pratt says. “I really respect what [Zappa] did, zeroing in on the freaks and giving them guidance and encouragement, especially a group of women, and not in this patronizing way. Just, ‘Oh, you’re funny and interesting. You should write songs. Why not?’ Maybe Warhol was more of a curator in a more image-based way, but I’ve always really liked that idea of ‘Anyone can be interesting, weirdness is good and maybe things sound bad and shambolic, but it sounds satisfying.’ I remember reading something actually about how, at some point, Robert Pollard had a tape of [the GTOs’ Permanent Damage] and would force Guided By Voices to listen to it on tour in the van. It’s a crazy record that I think most people would not like.”

That connectivity, how weirdness can exist as a mental telepathy between generations, finds a perfect home on Here in the Pitch. Jessica Pratt surrenders to lounge-singer pacing and odd phrasings (“And your beggar keeps a curfew at the door, all your fallacies are wasted in the fore and time”) and tenses (“It’s only lasted for a while”). The work is as out-of-sorts and displaced as it is comfortable and locked in. And that kind of duality—or juxtaposition, even—is as abstract and ambiguous as the album title Pratt lays before us. Like Yeats wrote long ago, Here in the Pitch is a rite “purified by tragedy”—but it’s purified by the tragedy of walking down dangerous streets propped up next to neighboring atoms, galaxies, mountains and oceans of beauty. The psychic activity Pratt has much respect for is alive and merciless on this record and on these songs and “in the stars waiting ‘til love’s aligned.”

Conversations around retro music will likely never conclude anytime soon, but there’s a timelessness about Pratt’s work that I particularly adore. I wouldn’t call it retro, though. Instead, Here in the Pitch is an accurate product of her environment in Los Angeles, a city that stands frozen in time while embracing the comforts and pacing of modernity. “It does feel like there are corners of the city that haven’t necessarily moved on,” Pratt says. “I think it’s the perfect combination of a big city and small city. It has a very relaxed feel and it has a harshness to it as well, but it’s enough of everything to get by. Sometimes I feel like I’m going a little crazy here, but I think, ultimately, it’s for the creative good.” On the lyric sheet being passed around during Here in the Pitch’s press cycle, Pratt included a Leonard Cohen quote: “The fact is that you feel like singing, and this is the song that you know.” Just as the “The storyline goes forever” line in “The Last Year” succinctly zips up the fables of a California she spent the bygone genesis of this record driving away from, the act of returning lingers. If the mystics of Los Angeles are as real as they sound—and if music can cut through the dead air of its nervous and receding outskirts—then there will always be a song for Jessica Pratt to come home to.

Matt Mitchell is Paste’s music editor, reporting from their home in Northeast Ohio.