Could a WA volcano erupt again in our lifetime? What would happen and how you can prepare

The most destructive volcanic eruption in United States history happened less than half a century ago in Washington state.

On May 18, 1980, the north side of Mount St. Helens, in southwestern Washington, collapsed, resulting in a massive explosion of magma and gasses. The initial eruption lasted about a day, and when all was said and done, 57 people were killed by the natural disaster.

A further 27 bridges and nearly 200 homes were also destroyed as a result of the eruption, according to the Washington State Department of Resources.

Forty-four years to the month after it happened, Washingtonians still remember the Mount St. Helens’ eruption. The event was so profound that May has been designated Volcano Preparedness Month to educate residents about Mount St. Helens and Washington’s four other active volcanoes.

Here’s what to know about Washington’s five active volcanoes, the chances of one erupting in the near future, and what you can do to prepare.

1980 Mount St. Helens eruption

While Mount St. Helens’ initial eruption on May 18 only lasted about 9 hours, it was enough to solidify the event as the most destructive in U.S. history.

Geologists and seismologists had an idea that something was brewing in Mount St. Helens about two months before the eruption. The first signs of activity occurred on March 16 when minor earthquakes were monitored around the peak, increasing in regularity as time went on, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

The eruption finally occurred on May 18, when a magnitude 5.1 earthquake caused the north flank of Mount St. Helens to collapse, causing one of the largest landslides in U.S. history. The collapse allowed a sudden release of gas-rich magma and superheated groundwater to explode from Mount St. Helens into the atmosphere.

Although state officials predicted an eruption was on the way and issued evacuation orders about a month before the eruption, the precise timing of the eruption couldn’t be predicted.

Devastation from the eruption covered 150 square miles with volcanic mudflow, blocks of shattered rock and volcanic debris and sediment in river channels. Over 195 million cubic yards of ash was expelled into the stratosphere, eventually covering about 49% of Washington’s land area. Ash quickly fell in areas like Olympia and Tacoma, approximately 70 miles away, and by May 19, an ash cloud had spread to the central U.S.

Future WA volcano eruption?

Washington’s most famous volcano is Mount St. Helens, but the Evergreen State has four other active volcanoes — Mount Baker, Glacier Peak, Mount Rainier and Mount Adams.

So, if there were to be another eruption in the future, would it come from one of Washington’s other volcanoes?

Likely not, University of Washington geologist George Bergantz told McClatchy News in a phone interview.

“The only volcano with real substantial activity in the last 4,000 years has been Mount St. Helens,” Bergantz said. “There’s some little residual heat in both Mount Baker and Glacier Peak; you get a few scattered hot springs. But in terms of ones that are certainly still connecting to the whole deeper process of subduction is Mount St. Helens.”

Subduction is the process of an oceanic tectonic plate running into a continental plate and sliding beneath it. In Washington’s case, the Juan de Fuca Plate is sliding underneath the North American Plate, resulting in the Cascades and related volcanoes.

Does that mean Mount St. Helens is set for another eruption soon? Not exactly.

Of course, it’s possible, but Bergantz said there are no guarantees that Washington will see another eruption in our lifetime.

What’s more likely to cause a threat in our lifetime is a volcano-related phenomenon called a lahar.

What are lahars, and why are they dangerous?

Volcanoes are just very steep piles of junk — or at least, that’s how Bergantz puts it.

“They aren’t like a normal rocky mountain that has a lot of internal strength,” Bergantz said. “They’re piles of ash with lava flows and lava domes that have had glaciers sitting on them and circulating water through them. So they become altered to clay and very unstable, and they’ve powered over the surrounding landscape.”

Because volcanoes are more unstable than regular peaks, they also make them more susceptible to falling apart.

In the worst cases, the whole side of a volcano can fall away, such as in 1980. But often, a lahar occurs, which are large deposits of muddy debris that can fall away from a volcano with little warning.

“As it travels down(hill), they typically get captured by the surrounding streams and rivers, which add more water and more power,” Bergantz said. “Most of the fatalities in the modern era from volcanic activity have been from lahars, not from the actual explosive part of the eruption itself.”

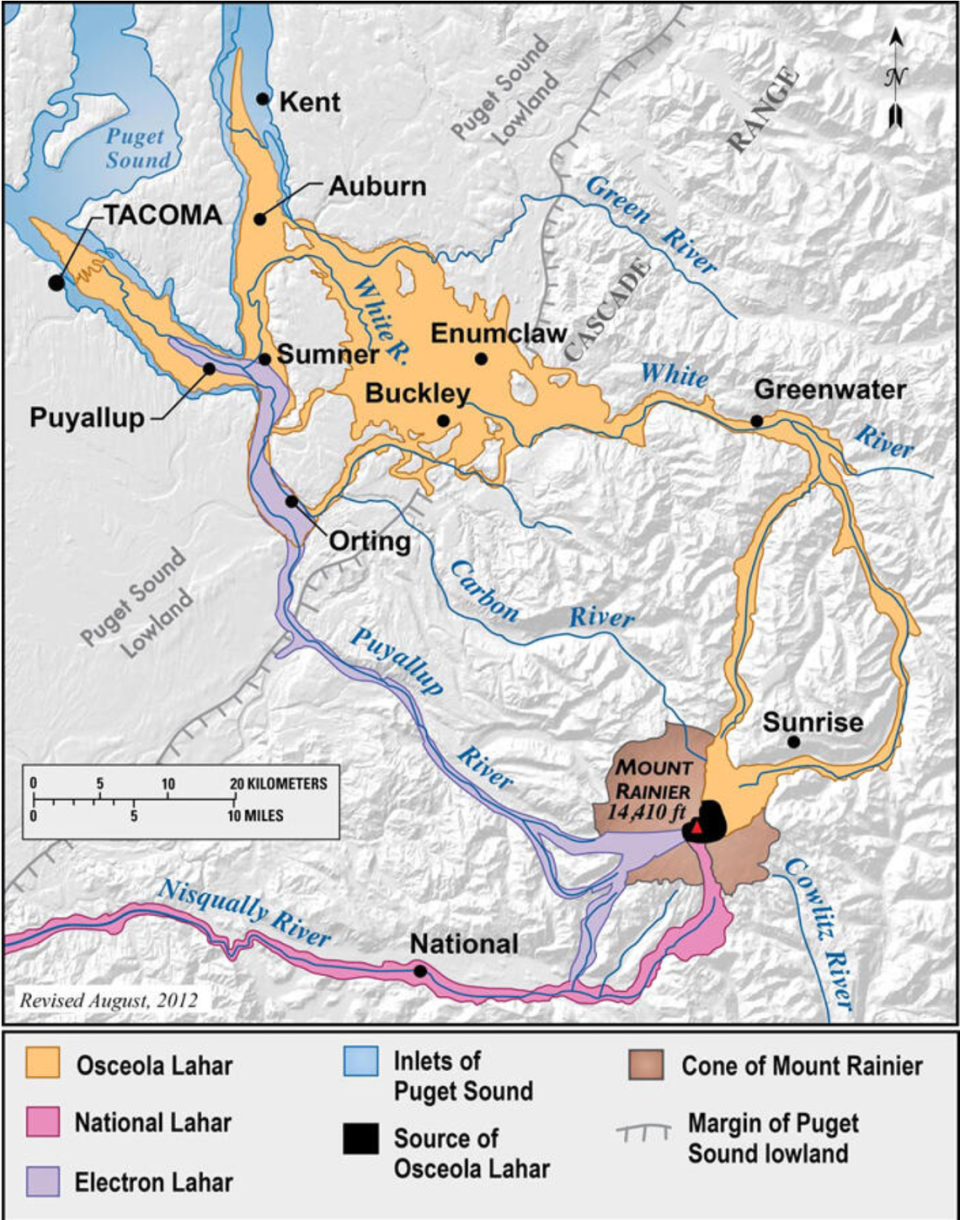

Bergantz added that Mount Rainier has a clear geological history of lahars, with some reaching as far as Seattle.

Lahars are much more frequent than eruptions but are also smaller events, Bergantz said. But he did say that he wouldn’t be surprised to see a medium-sized lahar event in Washington in the next 100 years.

Previous notable lahars from Mount Rainier have flowed down the White River (Osceola Mudflow, 5,600 years ago), Nisqually River (National Lahar, 2,200 years ago), and Puyallup River (Electron Mudflow, 500 years ago).

What if there was a major eruption in WA?

The precise timing of an eruption can be challenging to predict, but geologists and seismologists typically know something is coming far enough ahead of time to warn the public, such as with Mount St. Helens in 1980.

More recently, scientists recorded hundreds of earthquakes on the Reykjanes Peninsula in Iceland in December 2023, months before the first eruption from a volcanic fissure occurred near the town of Grindavík on March 16, 2024.

Like in 1980, state officials will likely have plenty of time to see the warning signs of an incoming eruption. Bergantz said an evacuation would only be called once scientists were near-certain of an eruption.

“Let’s think about Mount St. Helens,” Bergantz said. “If it had a return to a lot of seismicity, like we saw in 2004, with gas release and ground deformation, that would be the kind of scenario that might lead to evacuation.”

Not many people live around Mount St. Helens now, but similar warning signs around more populated areas, like Mount Rainier, could raise the alert level.

Once an eruption occurs, Bergantz thinks an economic crisis could envelope Washington and surrounding Pacific Northwest states. Not only will crops and wildlife be heavily affected by falling ash, but technology will also be affected.

“You don’t meet a lot of ash to completely destroy a car engine or a jet engine, the filters for a hospital, anything,” Bergantz said. “Any kind of sensitive equipment is compromised by even tiny amounts of volcanic ash.”

How to prepare for a WA volcano eruption

The Washington State Emergency Management Division works with multiple agencies in order to be prepared for different disasters. It’s prepared to respond to eruption impacts in each of the hazard areas through regional coordination plans.

For more information on emergency responses in your area, contact your local emergency management office.

What should I do?

If a volcano erupts in your area, evacuate immediately. There may be a designated public shelter or evacuation area. Text “shelter” plus your ZIP code to 43362 to find the nearest shelter.

Avoid low-lying areas like river valleys, get to high ground and shelter in place. Make sure you have methods to stay updated, through a phone, computer, radio, TV or other option.

Who should be prepared?

Check out this impact area map from the Washington State Department of Natural Resources.

How can I be prepared at home?

The Washington State Department of Natural Resources says it’s important to know the dangers and hazards faced at home, at work, where you relax and recreate and when traveling. The more you know, the better you can prepare.

The DNR also recommends the following preparations:

Have emergency supplies, food and water ready

Plan an evacuation route away from streams

Keep a pair of goggles and disposable breathing masks with your emergency provisions

Create a family emergency plan so your loved ones have a plan for contact in case of emergency

Stay informed by listening to media outlets for updates, stay alert for sirens warning of lahars

Check the Volcano Notification Service

Follow response plans from local and state emergency offices and local schools

Learn more about WA volcanoes

Usually, the public is invited to Johnston Ridge Observatory on the anniversary of the disaster, for a view of the Mount St. Helens lava dome. Due to damage from a 2023 landslide nearby, the observatory is closed and will likely take years to reopen.

However, there will be additional events throughout the month, through collaboration between the Washington Emergency Management Division and the U.S. Geological Survey Cascades Volcano Observatory.

Scientists and preparedness experts will be available to discuss the volcano at the Science and Learning Center at Coldwater on May 18 in commemoration of the 1980 eruption, from 10 a.m to 3 p.m. The center is at 19000 Spirit Lake Highway, in Toutle, at milepost 43 on State Highway 504.

An “Ask Me Anything” session on Reddit is scheduled for 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. on May 16 with volcano experts. Tune into u/WaQuakePrepare for answers. Anyone with a Reddit account can ask questions or leave comments.

Additionally, the Scientist in Charge at Cascades Volcano Observatory, Jon Major, is holding a talk at the Alberta Rose Theatre in Portland on May 22. Tickets are required.

The observatory has released a new poster to honor the heritage of the name given to the volcano by the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, Lawetlat’la. It also has a new paper on the risk management solutions developed at the volcano in the past 44 years.

You can also follow USGS Volcanoes on social media for posts on volcanoes, eruptions, preparedness and hazards every day.