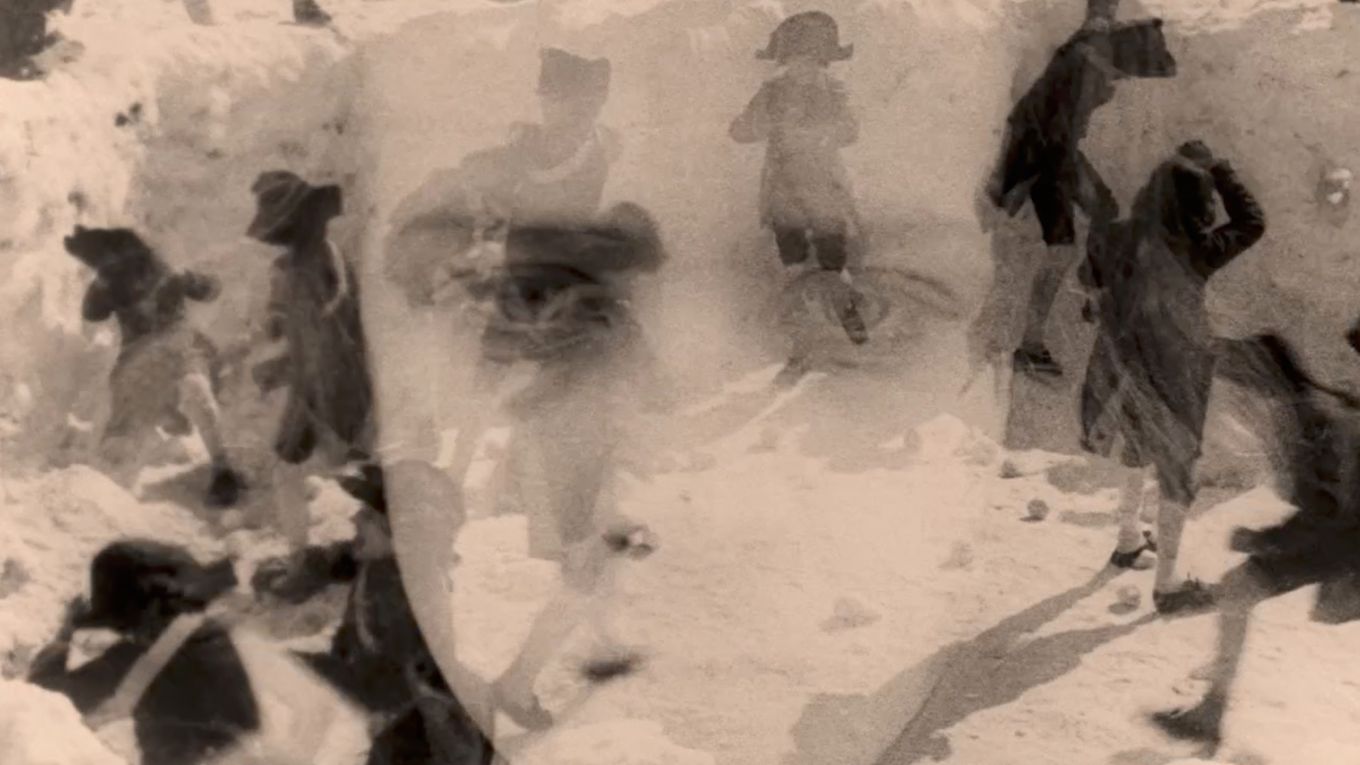

Napoléon as seen by Abel Gance for the opening of Cannes Classics, interview with Frédéric Bonnaud

Napoléon as seen by Abel Gance, screening for the opening of Cannes Classics of the first part (3h40) of Abel Gance’s monumental film (1927), in the presence of Costa-Gavras, president of the Cinémathèque Française, and of Frédéric Bonnaud, its managing director. Bonnaud describes the story of the exceptional reconstruction of this film, which took 15 years.

You use the term “reconstruction”, something beyond “restoration”. What were the steps of this?

The process lasted 15 years and cost 4 million euros. To understand this, you have to know that we knew of the “Apollo” version of the film, named after the Parisian theatre where Gance screened his edited version of the film, which lasted 9 and a half hours. Then there was a version that was conceived for officials, the President of the Republic, the Opéra de Paris, which lasted 11 hours and 44 minutes and which is known as the “Opéra” version. From the Apollo version, cuts were made to end up with a seven-hour version that we call the “grande version”. No one has seen this version since 1927. No one. Because you have to understand that Napoléon is a film without a negative. Nantes made a tragic mistake in sending it to the US for its screening there. It never came back. We thus carried out an expert assessment to find out if we had all of the necessary elements, including writings from Abel Gance, to reconstruct this “grande version”. And, after a century of more or less poor quality restorations, we were able to come up with a restoration that respected Gance’s wishes.

Was it feasible? We started on this gargantuan inventory work. We inventoried, in France, every canister that had parts of Napoléon, then looked in archives all over the world. We needed a Rosetta Stone to decipher this alphabet and it took us a long time to realise that Marie Epstein, a collaborator of Abel Gance and of Henri Langlois in the 60s, had made an extremely detailed written step outline of this “grande version”. We had the pattern, as they say in sewing, and from there things became possible.

“Nothing in the history of cinema has been ambitious in the way that this restoration-turned-reconstruction has been.”

Imagine a patchwork, a coloured blanket where you take little pieces of wool. We had just about everything, in complete disorder, and we knew how Gance wanted the film to be edited thanks to the step outline. Then we needed to find a machine to equalise all that, so that the transitions from one shot to another wouldn’t be chaotic. This nitro scan was developed by the Éclair lab, with whom we started to work. But they went bankrupt, which slowed down the work. But we had found the clips that we were missing, which was a real miracle. So it’s not a simple restoration but a real reconstruction of a film that no one had seen for a century.

What makes the magic of this film?

There’s the somewhat mythical story, the series of restorations that no one knew anything about, and then there’s the subject itself. A completely incongruous subject for a film that’s called Napoléon and not Bonaparte, even though the film stops well before Bonaparte becomes Napoléon. It’s supposed to be a biopic, as we say today, but, in fact, it’s nothing of the sort. It’s a sort of experimental odyssey, a film that tries to invent a new art, where film editing is being reinvented at the same time as cinema itself. It’s ridiculously ambitious and incredibly audacious in terms of editing and writing. Gance had a lot of ideas, he applied them all and they’re all good.

“Napoléon goes well beyond what we call a heritage film. It’s a film that was so ahead of its time, so experimental and innovative, which is what makes it very contemporary.”

And the score?

It’s a film without music, so without a score. We thus had to redo everything. We had to create a score for a seven-hour film. Gance had worked with the composer Honegger pour La Roue (The Wheel). That worked great for that film, but very poorly for Napoléon. Honegger wasn’t able to come up with a score. He only wrote a few parts that he didn’t like. So Gance did what was done at the time, a hotchpotch: the orchestra played various symphonic melodies, a little bit at random. We did the same thing, except there was nothing random about it. We worked with someone who has a computer in his head and knows the entire symphonic repertoire, even the most obscure pieces. His name is Simon Coquet. He first worked with already existing discs and recordings, but we were never going to work directly from these discs, that would be unworthy of a project such as this.

A single 7-hour recording made of segues between Spotify recordings…you’d have to be a genius like Simon to make that work! So then we needed a score. I don’t know if you realise that that’s several thousand pages. It’s amazing. And then from this score we had to finally find orchestras, the two symphonic orchestras of Radio France: a choir and a tenor, Benjamin Bernheim to sing La Marseillaise. We had to record to make the musical DCP of the first part for Cannes and then be ready to do live performances like those that we’ll be doing at the beginning of July at La Seine Musicale in Boulogne.