The Big Picture

- Dr. Strangelove is a black comedy masterpiece by Stanley Kubrick that satirizes the Cold War tensions of the 1960s, blending humor and horror.

- The film's original pie fight ending was scrapped in favor of a more poignant conclusion highlighting the cynicism of the military complex.

- Kubrick's direction and the performances of Scott and Sellers elevate the film, showcasing a delicate balance of tones and emotions.

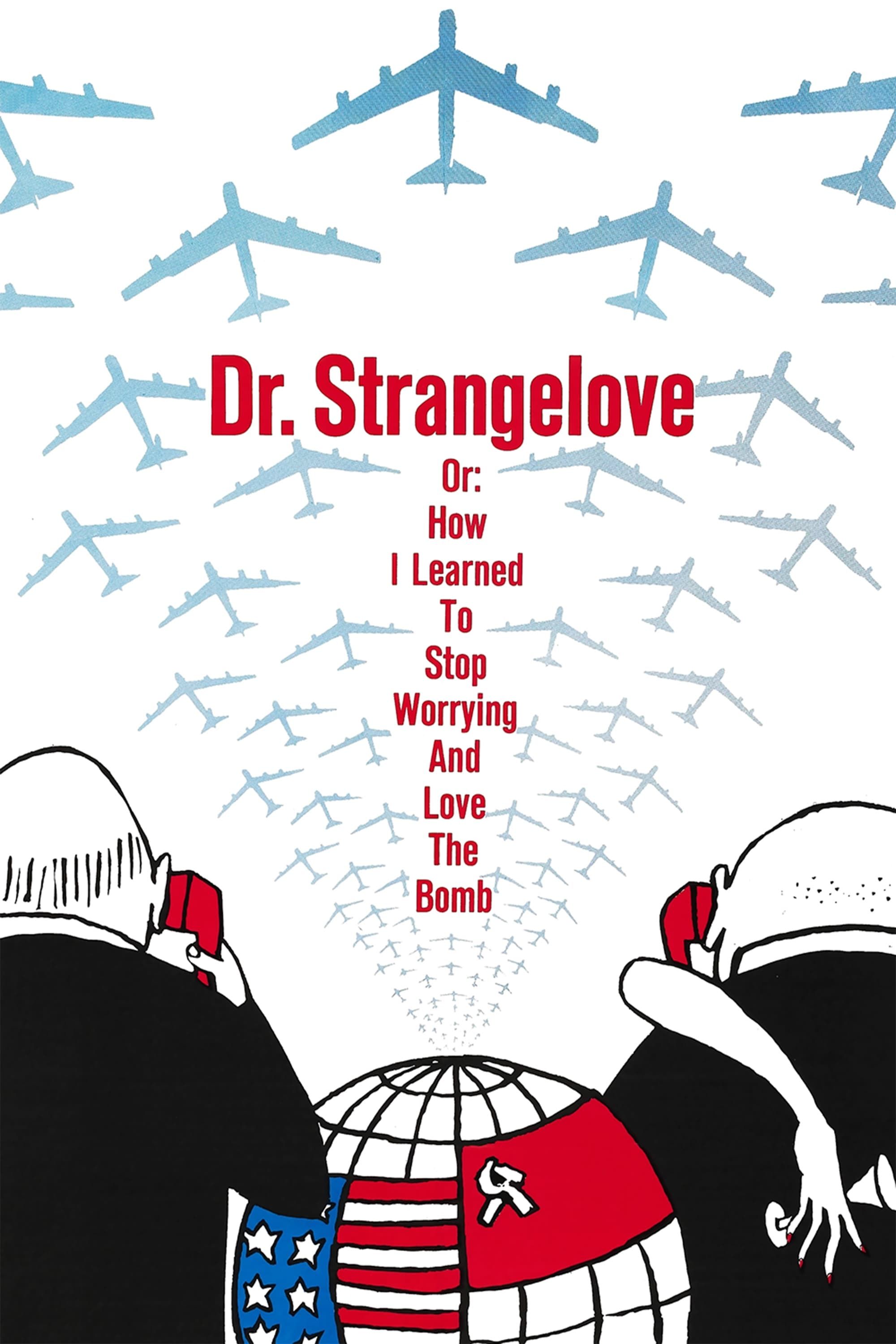

Only Stanley Kubrick could loosely adapt a thriller novel about nuclear war, turn it into a black comedy, have it be equally hilarious, profound, and prophetic, and ultimately amount to being a classic. Amid the rampant Cold War that was dominant in the political climate in 1964, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb imagines an absurdist, yet wholly plausible, comedy of errors that would plunge the world into nuclear destruction. The film is a magic trick perfectly topped off by an iconic ending that almost didn't materialize.

'Dr. Strangelove' Builds Toward an Apocalyptically Bleak Ending

After paranoid and war-minded General Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) goes rogue and orders a bombing attack on the Soviet Union, Dr. Strangelove centers on a group of politicians and military generals attempting to thwart the strike and avert global nuclear war altogether. The strategy in the Pentagon's war room is spearheaded by General "Buck" Turgidson (George C. Scott) and President Merkin Muffley (Peter Sellers, who plays two additional parts, including the titular role). While maintaining a tone of sincerity to start, Kubrick unwinds the austerity of the politicians and generals through moments of absurdism and slapstick comedy. The idea that these figures are responsible for the safety and livelihood of the free world is the relentless sucker punch that Kubrick sends his audience. A film as biting and cynical as Dr. Strangelove could only close out one way: the revelation that Dr. Strangelove is a Nazi, and a montage of nuclear explosions across the world, accompanied by the juxtaposed soft tune, "We'll Meet Again."

In a Kubrickian twist, this was not the intended ending upon filming. Instead of nuclear weapons, the director initially opted for pastries. Dr. Strangelove originally called for a climactic pie fight to erupt in the war room after the Russian diplomat, Alexi de Sadesky (Peter Bull), throws a custard pie at Turgidson, but inadvertently strikes the President. Within no time, every politician and general in the room begins hurling pies at each other in a chaotic ambush that mimicked the sensation of war combat. Rare archive photographs of the original ending are displayed on the British Film Institute's website. Believed to be destroyed, the footage of the pie fight climax was once screened in 1999 at the National Film Theater in London.

On paper, the intent and narrative throughline of this ending are evident. It confirms that these powerful figures are buffoons, and considering that the film embraced slapstick and farce throughout the runtime, the direction to lean into absurdity at full throttle when concluding the story is logical. Earlier in the film, Turgidson and Sadesky engage in a physical altercation nearby a buffet table inside the war room, where President Muffley insists that fighting should not ensue, as it was the war room. This is the only remnant of the alternate ending left in the final cut. The Strangelove and Ripper characters feel pulled from a sketch comedy show. The image of Slim Pickens riding a nuclear missile like a cowboy on a saddle remains prevalent in the culture. These flourishes of broad comedy are the brilliance of Dr. Strangelove, elevated by the fact that it was directed by the same resolute and calculated visionary behind 2001: A Space Odyssey and A Clockwork Orange down the line.

George C. Scott Didn't Want To Get Silly

Despite its roots in farcical comedy, a pie fight being the cherry on top of a satire on U.S. foreign affairs and the Cold War pushes the line of farce beyond its limits. Contrary to popular belief as a cold and sterile filmmaker, Kubrick flavors his movies with an array of tones and emotions. He can swiftly shift from black comedy to nightmarish horror in the same story. Dr. Strangelove is one of Kubrick's most accomplished bids at juggling dueling tones, seamlessly walking the fine line between a war room procedural drama (akin to the other 1964 Cold War film about an inadvertent nuclear crisis, Fail Safe) and absurdist comedy. Jokes are not derived from a routine of setups and punchlines, but rather patient construction of characters who mirror reality.

Kubrick's graciousness with the broad comedy of Dr. Strangelove is manifested in his direction of George C. Scott's performance as the blundering head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The actor was self-conscious about lowering himself to play a character of inherent buffoonery. Because this countered his vision, Kubrick asked that Scott give an animated and eccentric take as "practice" before playing it sincerely for a respective scene. As the final product entails, these "practice takes" were the real takes. That withstanding, Scott's austere demeanor is resonant on screen. Additionally, Sellers' performance as the President and exchange officer Lionel Mandrake is rooted in deadpan. The versatile actor was skilled in extracting the mildest humor in the most unassuming settings. Visually, Dr. Strangelove, as expected as a Kubrick film, is exceptionally crafted and precisely staged, utilizing shadows and fogs to enhance the fatalistic stakes at the heart of the story.

Why the Pie Fight Wasn't Right for 'Dr. Strangelove'

The film's tightrope walk of tones and genres would have been shattered by the alternate pie fight ending. The poignant satire is critical to the film's foundation and would have been muddied by this extreme case of farce. It loses sight of the sobering realities that were at the pulse of society in 1964. The pie fight is satirical, but not grim. The ending that the public has experienced is essential to conveying Kubrick's harsh cynicism towards the U.S. military complex and the manipulative fear churned by the government over the threat of a Russian nuclear attack. Without the current ending, Dr. Strangelove is merely a curious exercise, albeit an impressive one, of employing black comedy in a setting of despair.

There are two accounts as to why the ending of Dr. Strangelove was altered. Simply put, the conclusion was changed because Stanley Kubrick wasn't pleased with it. "I decided it was farce and not consistent with the satiric tone of the rest of the film," the director claimed in an interview in 1969. One other rationale for the change involves the assassination of John F. Kennedy, which occurred around the time of the film's intended release date. This caused Colombia Pictures to move its theatrical release to January 1964 in trepidation that the public would not want to see such a cynical film regarding national turmoil.

'Dr. Strangelove' Was Originally a Grim Thriller, Until Kubrick Did the Research

The Stanley Kubrick's war satire was originally written as a serious drama.

Dr. Strangelove's editor, Anthony Harvey, suggested on the film's 40th anniversary DVD release that the original ending was cut due to an inopportune line of dialogue by Turgidson. After President Muffley is hit with a pie to the face, the General exclaims "Gentlemen! The president has been struck down, in the prime of his life and his presidency!" According to Harvey, the pie fight would have stayed in the final cut if not for this line, as Colombia feared that it would offend the mourning Kennedy family. However, other parties have claimed that the original ending had been cut before Kennedy's death occurred.

If the story of the bizarre alternate ending to Dr. Strangelove proves anything, it is that luck and sharp instincts are paramount in the film industry. The fabric of film history could have been affected by the lack of a profound ending. If a juvenile pie fight closed out the film, maybe Stanley Kubrick does not begin a Golden Age run of modern classics. Maybe the cultural understanding of the complexities of the Cold War is never fully grasped because of this circumstance. Either way, the film community seems satisfied with how the film plays out.

Dr. Strangelove is available to rent or buy on Prime Video in the U.S.