The Big Picture

- An early cut of Star Wars was critiqued by Brian De Palma and Steven Spielberg, who made crucial contributions.

- George Lucas was part of New Hollywood directors like Spielberg and De Palma, but took a different creative path.

- Despite initial skepticism, De Palma and Spielberg played major roles in shaping Star Wars into a cultural phenomenon.

Everyone knows Star Wars, and just about everyone has some relationship with the franchise. It is synonymous with bankable franchise entertainment. The brand itself is the best marketing tool a studio can have. However, there was a time when George Lucas' space opera was a hard sell to studios, and even his closest collaborators and friends. An early screening of Star Wars (now known as Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope) in 1977, before being released in theaters and becoming a towering cultural phenomenon, contained a lost cut of the film, and if it's up to Lucas, this version will probably remain lost forever. The original cut of the film drew an uninspired response, to say the least, from executives at 20th Century Fox and his directing peers, Brian De Palma and Steven Spielberg. Luckily, these two wanted the best for their friend and made pivotal contributions to the film that launched the saga that changed pop culture forever.

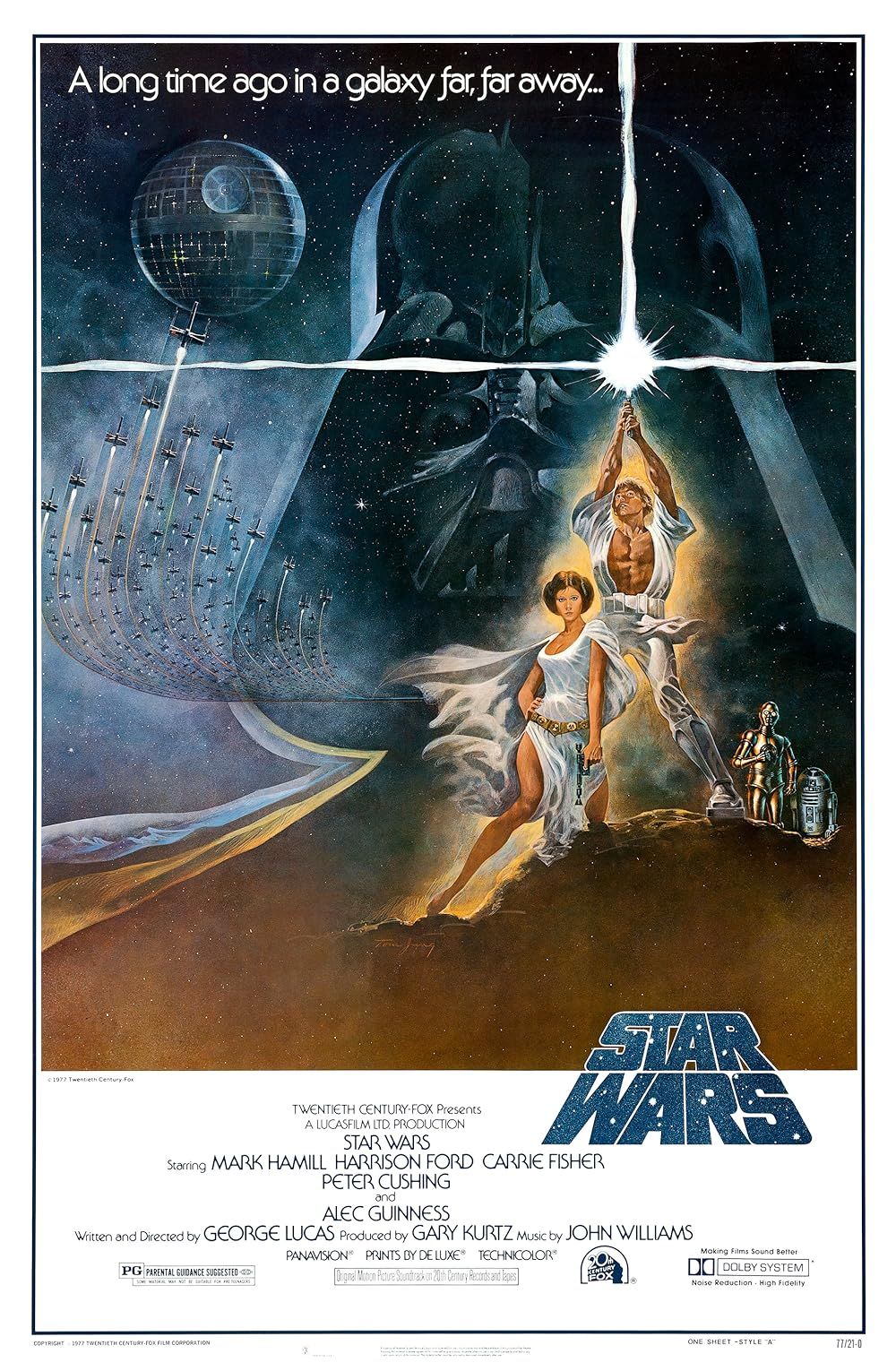

Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope

Luke Skywalker joins forces with a Jedi Knight, a cocky pilot, a Wookiee and two droids to save the galaxy from the Empire's world-destroying battle station, while also attempting to rescue Princess Leia from the mysterious Darth Vader.

- Release Date

- May 25, 1977

- Director

- George Lucas

- Cast

- Mark Hamill , Harrison Ford , Carrie Fisher , Peter Cushing , Alec Guinness , Anthony Daniels

- Runtime

- 121 minutes

- Writers

- George Lucas

- Studio

- Lucasfilm Ltd

George Lucas Was Part of a Vibrant Group of New Hollywood Filmmakers in the 1970s

The period of filmmaking during the late 1960s and early 1970s, known as New Hollywood, shattered the conventions of the classic studio system by telling raw and unflinching personal stories about deeply complex anti-heroes and aggressive politically charged thrillers. This wave of cinema, headlined by Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Easy Rider, The Godfather, and Taxi Driver, made films of classic Hollywood look tame. The movement practiced Andrew Sarris' theory of auteurism, which argued for the director as the author of a film. Naturally, the stars of this era were a group of "movie brats," Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas. Lucas' career took a major left turn relative to the career paths of his contemporaries. He was busy with a little space opera that no one could understand.

Lucas, an introverted, creative wunderkind, differed from his peers as an artist. In Peter Biskind's tell-all New Hollywood book, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Lucas cites that he was raised on television, and films did not mold him in the same obsessive manner as Coppola or Scorsese. Where New Hollywood embraced the morally ambivalent in everyday life, Lucas vowed to create a fantasy world that pitted good versus evil. Following the success of American Graffiti, his coming-of-age dramedy about the final days of innocence for teenagers in 1962, Lucas wanted to make "a kids' film that would...introduce a kind of basic morality. Everybody's forgetting to tell the kids, 'Hey, this is right and this is wrong.'" Graffiti supplied Lucas with the cachet to realize his space opera heavily inspired by Flash Gordon serials. Boldly calling his shot, Lucas demanded sequel and merchandising rights, which was seen as a laughable endeavor.

The New Hollywood troupe frequently collaborated, giving notes to improve each other's films. Coppola produced American Graffiti for Lucas, and endorsed Scorsese as a potential candidate to direct The Godfather: Part II. Decades later, Spielberg volunteered to help Scorsese direct a scene in The Wolf of Wall Street. Biskind wrote that Lucas suffered a bout of depression when writing Star Wars. In this down period, George's wife, Star Wars editor Marcia Lucas, called her husband's friend, Brian De Palma, and asked that he boost his spirits. During production, Lucas struggled to shoot action set pieces, and Spielberg offered to shoot second-unit footage. Lucas turned him down. Spielberg recalled that Lucas had a competitive streak in him, as he was adamant that Star Wars was going to dethrone Jaws as the all-time box office earner.

The Initial Screening of ‘Star Wars’ Was Criticized by Brian De Palma

In early 1977, Lucas was ready to screen Star Wars for a limited audience. At the screening with George and Marcia was Alan Ladd, president of Fox, De Palma, Spielberg, Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, Lucas' uncredited script doctor on Star Wars, and Jay Cocks, screenwriter and critic best known for his collaborations with Scorsese. Scorsese, feeling anxious over the post-production of New York, New York, was supposed to be there, but he canceled at the last minute. When the film ended, "there was no applause, just an embarrassed silence," wrote Biskind. The starkest red flag was the special effects or lack thereof. Because the effects were incomplete, Lucas substituted combat scenes with black-and-white dogfights from World War II films. Watching Star Wars without special effects is almost unimaginable.

When it was time for De Palma to weigh in on the rough cut of Star Wars, he pulled no punches. The legend states that De Palma grilled Lucas for every minute detail. He was baffled by the juvenile, Wizard of Oz-like tone, and mocked the concept of the Force. De Palma announced himself as the next Alfred Hitchcock thanks to a pair of lurid thrillers in Sisters and Carrie, so Lucas' desire to make a kid-friendly space odyssey with such an insular worldview was confounding. At a practical level, De Palma found the story incomprehensible. "The first act, where are we? Who are these fuzzy guys? Who are these guys dressed up like the Tin Man from Oz? What kind of movie are you making here?" a bewildered De Palma asked. In this lost cut of the original 1977 film, the crawl was there, but it was verbose, with De Palma saying during his roasting of Lucas, "It goes on forever. It's gibberish." On the podcast, Light the Fuse, the director claimed that he and Cocks re-wrote the crawl to make it concise.

George Lucas Secretly Replaced Darth Vader in Star Wars

Vader's unmasking was even more dramatic behind the scenes.How Brian De Palma and Steven Spielberg Helped Improve 'Star Wars'

Behind-the-scenes drama in Hollywood is full of legend-making. In many cases, stories about a film or figure in the industry are all hearsay. Peter Biskind's book, which helped shape the landscape of New Hollywood, has been criticized for portraying legend rather than fact. By the time De Palma appeared on the podcast dedicated to the Mission: Impossible series (who directed the first of the franchise), Light the Fuse, the widely-held belief was that De Palma hated Star Wars. "We all saw it as a terrific thing that George had done," he said, clarifying that he understood the reasoning behind the lack of special effects. However, he did confirm that he ridiculed the Force, mainly due to its vague name. De Palma's biggest point of contention was the narrative that Spielberg was the only supportive voice in the room. The legend of the initial Star Wars screening also states that Spielberg was Lucas' only friend amid the firestorm of criticism thrown at him. "The fact that Steven says that only he saw the possibilities of Star Wars, that’s not really true." De Palma told Light the Fuse.

Spielberg's reaction to seeing Star Wars for the first time, as depicted in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, is that of an overly supportive parent coaching their child in sports. "George, it's great. It's gonna make $100 million," he affirmed to Lucas. That night, Alan Ladd called Spielberg about the potential of this project, and the director, who ostensibly created the blockbuster with Jaws, insisted that Star Wars would be "a huge hit." 45 years later, Spielberg would clarify his initial reaction to the film in Light & Magic, the Disney Plus documentary about Lucas' visual effects company, Industrial Light & Magic. "To say it was not finished is a kindness," Spielberg said of Star Wars' rough cut in the docu-series.

Spielberg also shared De Palma's confusion surrounding the context of the story. "What is this menagerie of imagination, George, that you've invited us to see and tear apart!?" he exclaimed. Spielberg's account of the initial Star Wars screening depicts him as far more skeptical of Lucas' vision. However, he was still supportive, as he claimed that only he and Alan Ladd "loved" the movie in its primitive condition. More than his endorsement at the first screening, Spielberg's greatest contribution to the Star Wars franchise was introducing Lucas to the great John Williams. Williams had previously worked on Jaws, with his minimalist score making everyone scared to go in the ocean for years. The entire franchise and the galaxy far, far, away would be a shell of itself without the sweeping orchestral wonder and adventure in Williams' score.

Justifying their harsh criticisms, Brian De Palma and Steven Spielberg made invaluable contributions to Star Wars that have remained a staple of the franchise nearly 50 years later: the opening crawl and introduction of John Williams to George Lucas. De Palma and Spielberg provided textual and emotional clarity, respectively. By all accounts, the uninspiring reaction to the rough cut of Star Wars was in dire need of assistance. Every triumphant cinematic story has humble beginnings, and for Star Wars, the conception of Lucas' space opera appeared to be dead on arrival. Thankfully, Lucas had ingenious filmmaking friends at his disposal.

Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope is available to stream on Disney+ in the U.S.