Reasoning In The World Of Democracy And Demagoguery – OpEd

By Leonard Weinberg

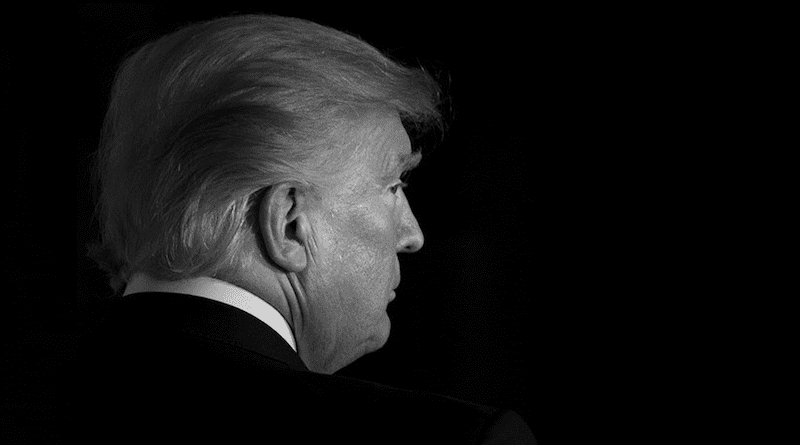

The coming presidential election contest between President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump has aroused serious worry not only in the United States but among observers from other Western democracies. Many clear-thinking analysts such as William Cristal, Timothy Synder and Liz Cheney worry that a Trump victory would likely bring an end to America’s democratic experiment. They appear to think that this outcome would represent an aberration — something relatively new under the Sun.

But, as President John Adams wrote to a friend, John Taylor, in 1814, “Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes itself and murders itself.” This comment came from one of America’s Founding Fathers, someone who shaped the ‘experiment’ about whose future he seemed doubtful.

Adams’ skepticism about the democratic prospect was likely influenced by the outcome of the French Revolution, with the impending restoration of the Bourbon Monarchy. Adams, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and the other founding fathers had examined the historical record and read the works of the ancient Roman and Greek philosophers. They were also well aware that previous democratic experiences had flourished for relatively brief periods of time and collapsed or were superseded by other forms of rule. Athenian democracy, the Roman Republic, the city-states of medieval northern Italy had all given way to astrongman- or strong-family-rule or to the fusion of church and state after varying lengths of time.

It is true that the US constitution was made in the name of “We the People.” But after that prologue, the Founding Fathers did what they could to protect the federal government from the will of the people in whose name it was conceived, or at least rhetorically conceived.

Accordingly, the only federal institution directly accountable for the wishes of voters was the House of Representatives. The Senate, the presidency and the Supreme Court were all originally insulated from direct popular control through various filters — the state legislatures in particular. It was really only over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries that constitutional amendments provided greater popular control over the country’s national institutions. That was when the beginnings of democratization took hold.

But did the Founding Fathers get it right? Was insulating the American national government from popular control beneficial? Perhaps we could learn from their decisions. Plato and Aristotle believed in the primacy of reason as a principle to govern the conduct of the individual, and by extension the polis or government, as well. When passion dominates over reason, disorder and chaos follow.

The people, the Greek philosophers reasoned, tend to be dominated by passion and emotion rather than reason. That is why they believed democracy was an inherently unstable form of rule. The will of the people was volatile and capricious, so much that demagogues (individuals skilled in manipulating the people through captivating or transgressive oratory) would come to dominate democratic life. Under these conditions, rule by the people would inevitably give way to rule by the demagogue.

Can democracy be good government?

The late historian James MacGregor Burns argued that, unlike the ancient Greek city-states which never had more than a few tens of thousands of citizens, Americans are too numerous to fall under the spell of a self-enamored demagogue, not to mention too educated and too prosperous. To what extent is this true?

Surveys of American public opinion provide a clue. During the mid-to-late 1950s, when Joseph McCarthy sounded alarms about supposed communist infiltrators, researchers like Samuel Stouffer sought to measure the extent to which Americans supported the protections provided citizens by the First Amendment. Taken as abstract principles, most members of the public agreed with the First Amendment’s protections of free speech, public assembly and worship. Attitudes changed substantially though when the questions became more specific: Do you support the right of a communist to speak in public? Should the books of atheists and socialists be available at public libraries? Posed in specifics, support for the First Amendment protections broke down, with significant percentages of the respondents denying the rights to which they had agreed in the abstract.

Opposition to these more specific probes was not randomly distributed in the public. Individuals who had completed fewer years of education and displayed lower socio-economic status were the least likely to support First Amendment protections when they were expressed in concrete terms. Why?

Various analysts, like sociologists Seymour Lipset and Earl Raab, maintain it is a matter of cognitive sophistication — a kind of sophistication that normally comes with educational attainment. In the United States at least, the ability to see shades of gray between black and white is typically linked to the number of years in school respondents have completed.

The effect of education on American voters is most obvious in Trump’s electoral appeal. Opinion surveys have revealed that Trump’s constituency is disproportionately drawn from less educated segments of the American public. Those most likely to be governed by passion over reason, as the ancient philosophers maintained. Indeed, they seem to be vulnerable to demagoguery, identity politics and conspiracy theory.

Trump’s public performances are characteristically directed at American voters more motivated by passion more than reason, voters who perceive the world in black-and-white terms and whose find his oftentimes vulgar and contempt-laced speeches irresistible.

The crucial question before the house is whether or not this segment of the electorate is sufficiently large to restore Trump to power. Are college-educated Americans numerous and influential enough to deny Trump a second term of office? The fate of the American experiment depends on the answers.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

- About the author: Leonard Weinberg is foundation professor emeritus at the University of Nevada. Over the course of his career he has served as a visiting professor at King’s College, University of London, the University of Haifa (Israel), and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He is the author of many books on terrorism and right-wing politics.

- Source: This article was published by Fair Observer