100-year-old who shaped Israeli photojournalism takes stage to share Holocaust survival

Cultural icon Dan Hadani survived the Lodz Ghetto and multiple Nazi camps. A lifelong chronicler, he continues to tell his story at the National Library of Israel

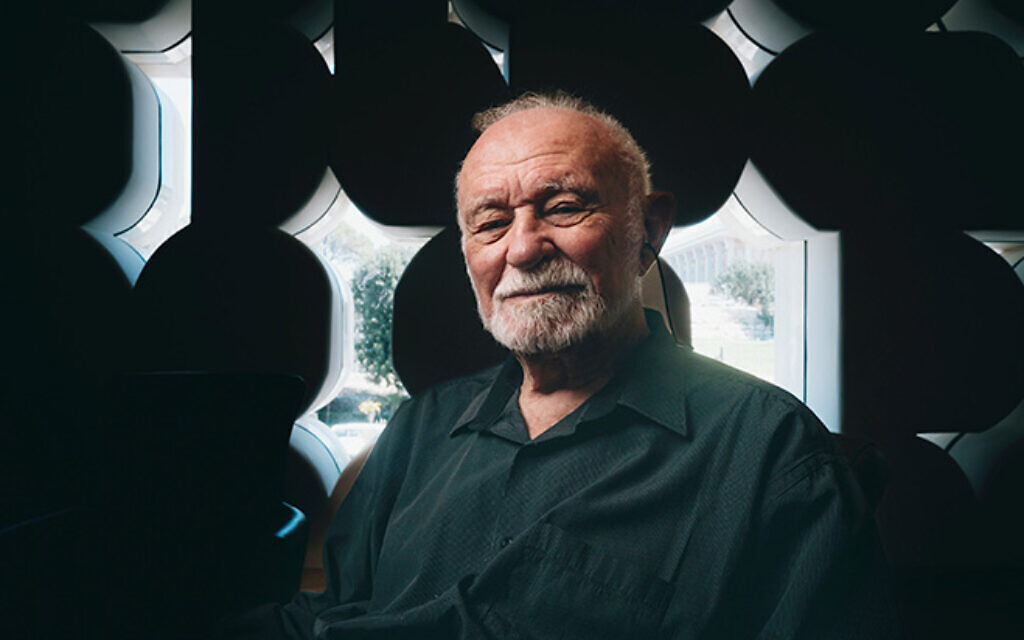

Dan Hadani, only three months away from his 100th birthday and looking decades younger, told a rapt audience of 300 his Holocaust survival story at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem on Sunday night in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Hadani spoke in detail — often correcting his interviewer. He only occasionally searched for a forgotten word in Hebrew that accidentally came out in German, Italian, or Polish.

Before he began documenting and speaking publicly about his experiences in the Holocaust, Hadani had already made his mark on Israeli history through his work as the founder and head of the Israel Press & Photo Agency.

During his decades of photojournalism in Israel, Hadani rubbed shoulders with prime ministers Golda Meir, Yitzhak Rabin, Menachem Begin, David Ben Gurion, and many other world leaders, including Egyptian president Anwar Sadat.

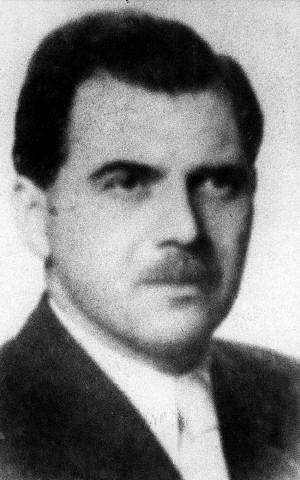

But his first brush with a famous — or at least infamous — individual came during a “selection” at the Auschwitz extermination camp that was conducted by the sadistic torturer, Dr. Josef Mengele, also known as “the Angel of Death.”

After being subjected to harsh physical tests to exhaust them, Hadani and hundreds of other sick, malnourished prisoners were made to stand in neat rows of five before the doctor, Hadani recounted on Sunday night.

Mengele went down the lines slowly, saying nothing. He simply pointed a finger at whichever man he was interested in, and they would be removed from the line.

The doctor wordlessly pointed in Hadani’s direction, to which he responded in German, “Did you mean me?”

“Stand still, dog,” Mengele barked, pointing to the man behind Hadani.

Everyone was shocked — nobody ever spoke to Mengele, and the doctor certainly never spoke to the prisoners during these selections.

Zionist roots in Poland

Born Dunek Zloczewski in Lodz, Poland, in 1924, Hadani came from a staunchly Zionist family. They tried to move to Israel (then Palestine) twice before the war, but only made it as far as Italy before turning back and deciding to stay in Poland.

In 1939, when the Germans invaded, the Zloczewski family moved into a small apartment in the Jewish ghetto, where they lived in abject poverty. Hadani’s father passed away three years later.

As a young man, Hadani was witness to all manner of horrors at the hands of the Nazis. When they first came to Lodz, 15-year-old Dunek Zloczewski watched the German soldiers force grown men to strip down to their underwear and crawl on their hands and knees while they were beaten.

He recalled while onstage at the National Library, “Some of them were pushed into the sewer on the side of the road. I saw on one side, they blocked up the [sewer’s] exit, and on the other side, they kept pushing in more and more people. They were murdered that way.”

In August of 1944, the residents of the Lodz Ghetto, Hadani among them, were loaded into train cars and taken to Auschwitz.

It took at least an hour to load people into each car, and the train did not leave until all cars were loaded. Hadani said there were about 15 or 20 cars in total, each with 120 people inside.

“It was a nightmare,” Hadani said.

After about six days of travel with no food or water, the Lodz passengers who remained alive arrived at Auschwitz and were met by squadrons of SS officers, who separated the men from the women.

“The train car opened, and there were terrible screams,” Hadani recounted, his voice still carrying a a faint echo of the terrified 21-year-old who managed to survive the hellish train ride.

“Within seconds, they separated me from my sister and mother. We couldn’t even say goodbye or hug,” he said.

This was the last time Hadani saw his family.

Death valley

In the short journey on foot from the train to the entrance of the camp, Hadani walked past the open train cars and saw inside the dead bodies of those who had not survived the journey laid out on the floor alongside buckets of human waste.

Before they could officially enter the camp, the Nazis made their prisoners undergo a “disinfection” process.

“They came with razors and took off all of our body hair — everywhere you can imagine. These razors would be used for 10 or 20 people. Some of them were broken… Of course, we were all bleeding from all kinds of places by the end of it.”

During his time in Auschwitz, Hadani managed to survive several rounds of “selections,” or cullings, in which those who were too weak to work were sent to the gas chambers.

“The first selection was between women and men,” he explained matter-of-factly. “Then it was between life and death.”

In the following months, Hadani was moved from one camp to another and treated like an animal, given only the bare minimum needed to continue surviving. The prisoners were exposed to the bitter cold of an Eastern European winter with no protection.

“I would wake up from screams at night because the rats were eating people’s flesh,” Hadani recalled. “[Due to frostbite,] they did not feel it until the rat reached living flesh, at which point they awoke and screamed.”

“I was lucky,” he said. “I found a discarded sack and made myself socks.”

On May 2, 1945, the Wöbbelin concentration camp — where Hadani had ended up after a 30-kilometer death march and two more relocations — was liberated by the US Army. Twenty-one years old and weighing only 40 kilograms (88 lbs), Hadani returned to Lodz to find that he had no family left.

With no reason to stay in Poland, Hadani traveled to Italy with the intention of moving to the Holy Land.

After spending some months learning seafaring with fellow Zionist Holocaust survivors in southern Italy, Hadani arrived in Israel in June 1948 and was conscripted into the navy the following day.

In the army now

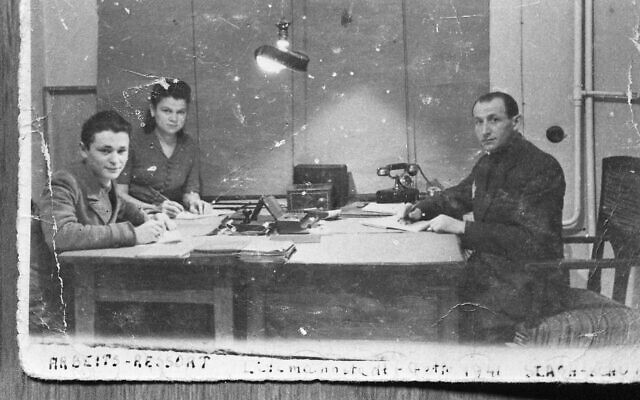

This marked the beginning of Hadani’s 17-year career in the IDF, fighting in the War of Independence and continuing to serve in the navy, then the Intelligence Corps, and finally the IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, where he discovered his passion for visual media and journalism.

When he was discharged from the military in 1965, Hadani worked for two years as a freelance journalist before founding the Israel Press & Photo Agency, which was active until 2000. At the age of 75, after nearly four decades, Hadani closed the office for news coverage and began digitizing the negatives from his extensive collection, which he hoped to eventually sell.

He spent 15 years carefully scanning photos into the database, but Hadani could not find a buyer. Already in his 90s, he was afraid that the collection would fall into the wrong hands after he died. He began making arrangements to shred all of the negatives and slides when he was connected with Dr. Ruth Calderon, who was then the head of the culture and education department of the National Library of Israel.

This was how, in 2016, the National Library received 400,000 digitized negatives and one million more negatives that had yet to be digitized, in addition to thousands of slides.

It was around this time, in his early 90s, that Hadani decided to tell his life story publicly online. Until that point, he said on Sunday, he was afraid to share the fact that he was a Holocaust survivor for fear of seeming weak or helpless.

The 300 people gathered in Jerusalem on Sunday night saw no signs of weakness or helplessness in the 99-year-old. Though he is a highly gifted storyteller, able to vividly describe his memories from decades past, it was difficult to imagine that the strong-willed centenarian on stage had ever been a frail 21-year-old victim of the Nazis.

“This is an historical moment,” Moriah Bar-Gil, the National Library’s Cultural Event Producer, told The Times of Israel after the event.

“Three hundred people came to hear a man talk b’guf rishon, [in first person] about his personal stories,” said Bar-Gil. “I think that’s the essence of the National Library.”

Are you relying on The Times of Israel for accurate and timely coverage right now? If so, please join The Times of Israel Community. For as little as $6/month, you will:

- Support our independent journalists who are working around the clock;

- Read ToI with a clear, ads-free experience on our site, apps and emails; and

- Gain access to exclusive content shared only with the ToI Community, including exclusive webinars with our reporters and weekly letters from founding editor David Horovitz.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel