Major Works by Henri Matisse and Ellsworth Kelly Go on View at Fondation Louis Vuitton

The acclaimed Paris art destination is hosting a pair of knockout exhibitions that explore two visionary talents just in time for the Summer 2024 Olympics

Set of works hung in the auditorium of the Louis Vuitton Foundation as part of "Ellsworth Kelly: Shapes and Colors, 1949-1954". Photo: Marc Domage; Courtesy of Foundation Louis Vuitton

After a hefty diet of blockbuster shows—the most recent dedicated to Mark Rothko and the previous to a dialogue between Edouard Manet and Joan Mitchell—it is with some relief that visitors to Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris will find its modern baroque interior divided into three this summer.

One exhibition, squirreled away on the upper floor, is devoted to art and sport, a little lip service to the city’s hosting of the Summer 2024 Olympic Games. But the draw is the other two: “Matisse: The Red Studio”; and “Ellsworth Kelly: Shapes and Colors, 1949-1954.” While both may have been seen by Americans in their U.S. formats—at the MoMA in New York and Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Maryland, respectively—they come here quite changed. Matisse is depicted journeying to abstraction for the first time with his 1911 painting, The Red Studio; Kelly’s is a life survey that shows him finding the sweet spot between painting and sculpture. If they share anything it is an interest in economy and color.

View of the Louis Vuitton Foundation auditorium with the Ellsworth Kelly stage curtain. Photo: Marc Domage; Courtesy of Foundation Louis Vuitton

“Ellsworth Kelly hated to talk about influences,” says Suzanne Pagé, the artistic director of the foundation, who has been in place since its inception in 2006 and knew the artist well. “But he looked to the past—Romanesque churches, Poussin, the whole of Paris.” His Spectrum paintings from the 1950s, shown here, were started in the French capital, which he had come to on a GI grant after the Second World War. Their denouement, a bespoke curtain that Kelly designed for the foundation’s auditorium and the last commission completed in his lifetime, here becomes part of the exhibition.

“He worked directly with Frank Gehry,” says Pagé of the American architect who designed the building. “If Gehry is baroque and exaggerated, then Kelly saw it as the perfect setting for his work. He said he’d always dreamed of a commission like this, to put color into space.”

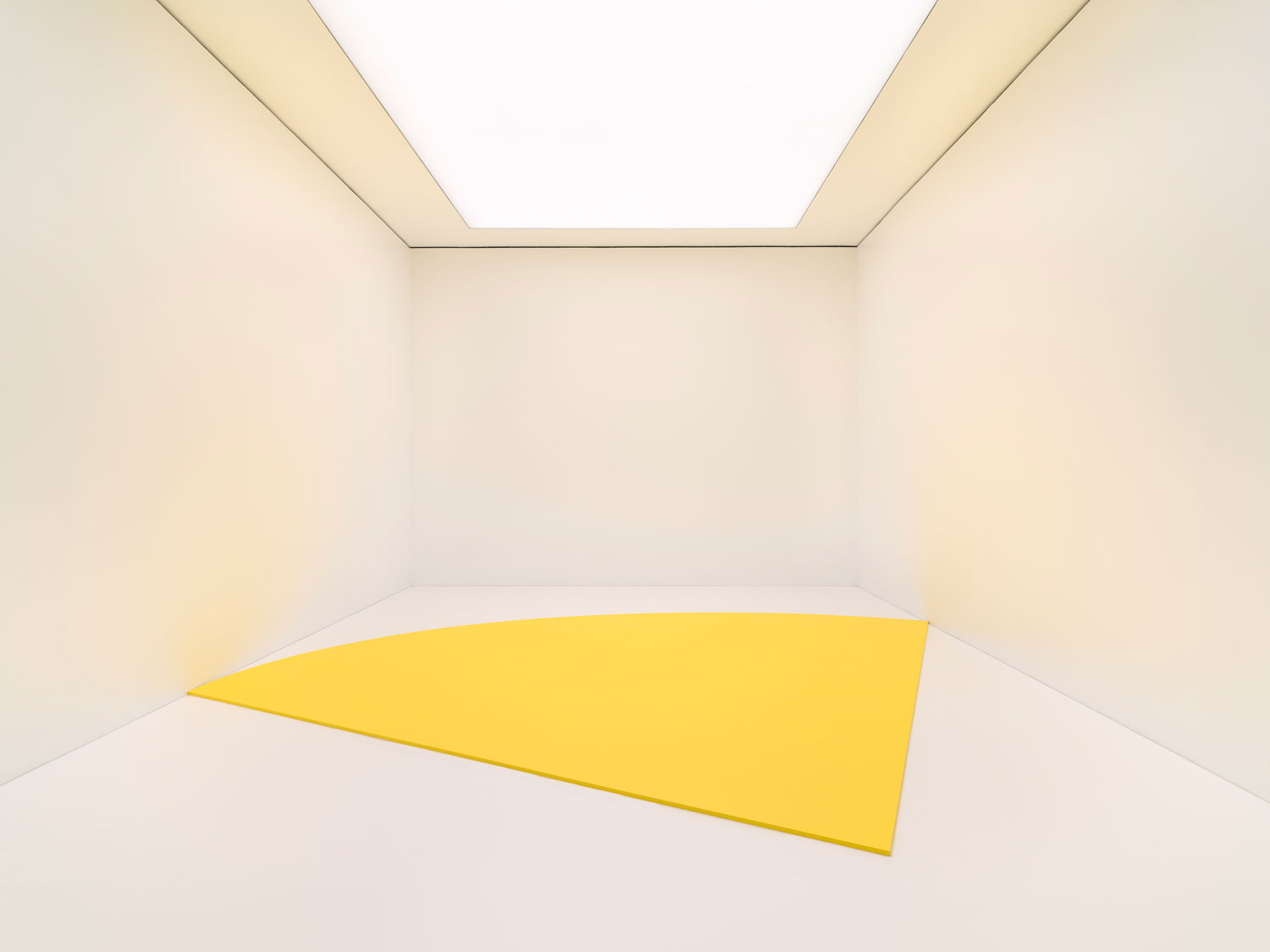

Ellsworth Kelly, Yellow Curve, (1990). Photo: Ron Amstutz; Courtesy of the artist

Throughout the galleries, Kelly’s ever-evolving explorations into an art that the viewer feels as much as sees is played out in his brilliantly colored forms. His early interest in chance (lessons learned from John Cage and Hans Arp) is elaborated in a handful of works, and his passion for work created specific contexts is everywhere. Painting for a White Wall is just that—five colored stripes of which the fourth (white) one makes it appear to stop and start.

Kelly’s partner, Jack Shear, who was with the artist from 1982 until Kelly’s death in 2015, is on hand for every exhibition of the work. “I was 30 years younger than him,” says Shear. “I think that was partly the attraction, to have someone to carry on after he died. Do I miss him? Not really, because I’m with him everyday. I’m channelling him.”

Henri Matisse, The Red Studio, (1911). Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Foundation Louis Vuitton

Up on the first floor, Matisse’s The Red Studio marks the artist’s dramatic break with his figurative past. “The painting initially depicted a three-dimensional space, in classic perspective,” says Pagé of the painting, which shows the artist’s own studio, filled with his own paintings and objects. “The walls were blue, the floor was pink, the furniture was ochre. Then a month later, he came back to it, and had a vision, and covered the entire canvas in red. All great works are something that escape from their creators,” Pagé continues. “It’s not a decision. It’s a vision.”

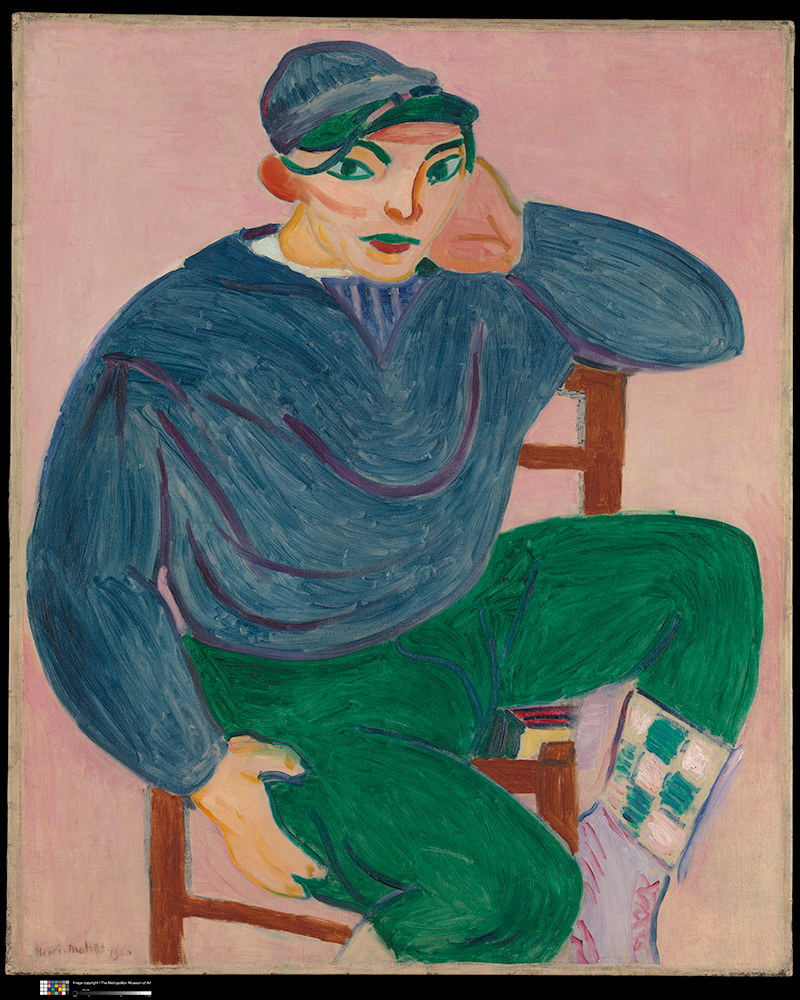

That vision is as much a rendering of a real space as an insight into the artist’s mind. The idea of the artist’s studio, once depicted as a place of industry, filled with assistants and models, had now become the practitioner’s personal space for introspection and reflection. It hardly matters if these works were in reality in his sightline or simply in his head. Still, it’s a great excuse to reassemble works by the master, so around the walls of the gallery, and on plinths, are all those he chose to put in the Red Studio. A nude draped with a white scarf, a decorated plate, a painting of a cyclamen, a bronze bust, a young sailor, charcoal sketches, a windmill in Corsica.

Henri Matisse, Young Sailor II (1906). Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Foundation Louis Vuitton

Matisse’s most devoted benefactor, Russian textile magnate Sergei Schukin, had been keen to acquire the original version. But after Matisse’s visionary readjustment, he reneged on the deal. (“He said he’d keep buying the figurative ones,” explains Pagé.) The painting languished until it was acquired in 1927 by British aristocrat David Tennant, who hung it in the Gargoyle Club, a legendary London haunt for bright young things with a fantastical interior. Eventually it went to MoMA in New York. Now it’s rightfully seen as a Matisse masterpiece, and here it’s surrounded by many more. It’s a joyful reunion.

Both “Matisse: The Red Studio” and “Ellsworth Kelly: Shapes and Colors, 1949–1954″ are on view until September 9, 2024.