The Big Picture

- Vertigo's groundbreaking use of the dolly zoom introduced the "Vertigo effect" that is still used in movies today.

- Saul Bass transformed film opening credits into an art form with his iconic designs for Vertigo and other classics.

- The title sequence of Vertigo was the first in film history to use computer animation, created by John Whitney and Saul Bass.

For any passionate film connoisseur, Vertigo speaks for itself. At the early stage of cinephilia, everyone is introduced to the film. Celebrated as Alfred Hitchcock's masterpiece, Vertigo is also one of the finest achievements in the medium's history. Overlooked upon release, Vertigo is a haunting portrayal of obsession and the male gaze, as well as a biting commentary on the controlling nature of filmmaking — something that hit home with Hitchcock, who was notorious for his demanding absolute perfection in his vision. To express these rich ideas on the screen, the Master of Suspense pushed the limits of visual language, perfecting unprecedented dolly zooms with his camera. However, this wasn't the only visual innovation. From the get-go, Vertigo establishes itself as a game-changer thanks to its alluring opening credits, the first film sequence to feature computer animation.

Vertigo

A former San Francisco police detective juggles wrestling with his personal demons and becoming obsessed with the hauntingly beautiful woman he has been hired to trail, who may be deeply disturbed.

- Release Date

- May 28, 1958

- Director

- Alfred Hitchcock

- Cast

- James Stewart , Kim Novak , Barbara Bel Geddes , Tom Helmore , Henry Jones , Raymond Bailey

- Runtime

- 128 mins

- Main Genre

- Mystery

- Writers

- Alec Coppel , Samuel A. Taylor , Pierre Boileau , Thomas Narcejac , Maxwell Anderson

'Vertigo' Was a Groundbreaking and Innovative Cinematic Feat

Alfred Hitchcock's cinematic golden age in the 1950s peaked with Vertigo, a hypnotic romantic thriller about a retired police officer, John "Scottie" Ferguson (Jimmy Stewart), hired to trail an enigmatic but striking woman, Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak). The film, despite its basic set-up, forgoes following conventional storytelling beats once the narrative comes into full swing. Scottie becomes obsessed with Madeleine until she is mysteriously killed. Later, Scottie falls in love with another woman, Judy Barton (also Novak), who looks just like Madeleine. Scottie becomes entranced with Judy, as he molds her to look exactly like Madeleine, even though Judy and Madeleine are the same person. On the outside, Vertigo is an impenetrable story — too convoluted and too much of a labyrinth on Hitchcock's part. Just like its protagonist, the viewer is slowly warped by the intoxicating themes of obsession and perverse romance, which were especially provocative ideas in 1958.

Scottie, who witnessed his partner fall to his death off a tall building, suffers from acrophobia (a fear of heights). As the title indicates, Hitchcock points the camera from Scottie's point of view whenever Scottie stands at a high elevation, and we experience a dizzying sensation akin to the symptoms of vertigo. The disorienting effect created by the dolly zoom is referred to as the "Vertigo effect," as the film is the first recorded use of this shot, now commonly used in movies today. Hitchcock's ingenious method of capturing Scottie's fear (which is ultimately a condition of his obsession) is deployed when Scottie looks down below as he hangs on for dear life atop a building at the beginning of the film, and when he looks down the steps of the mission bell tower while being lured by Madeleine to reach the top floor. As explained in a behind-the-scenes DVD feature, the Vertigo effect was "achieved by a combination of zooming forward and tracking backward simultaneously." To seamlessly execute this elaborate shot, Hitchcock's team built a large-scale model of the staircase inside the bell tower. The model was filmed on its side to mirror Scottie's dizzying feeling.

The Classic Film That Alfred Hitchcock Called "Almost Perfect"

Game recognized game, even back in 1924.Why 'Vertigo's Opening Credits Were Revolutionary

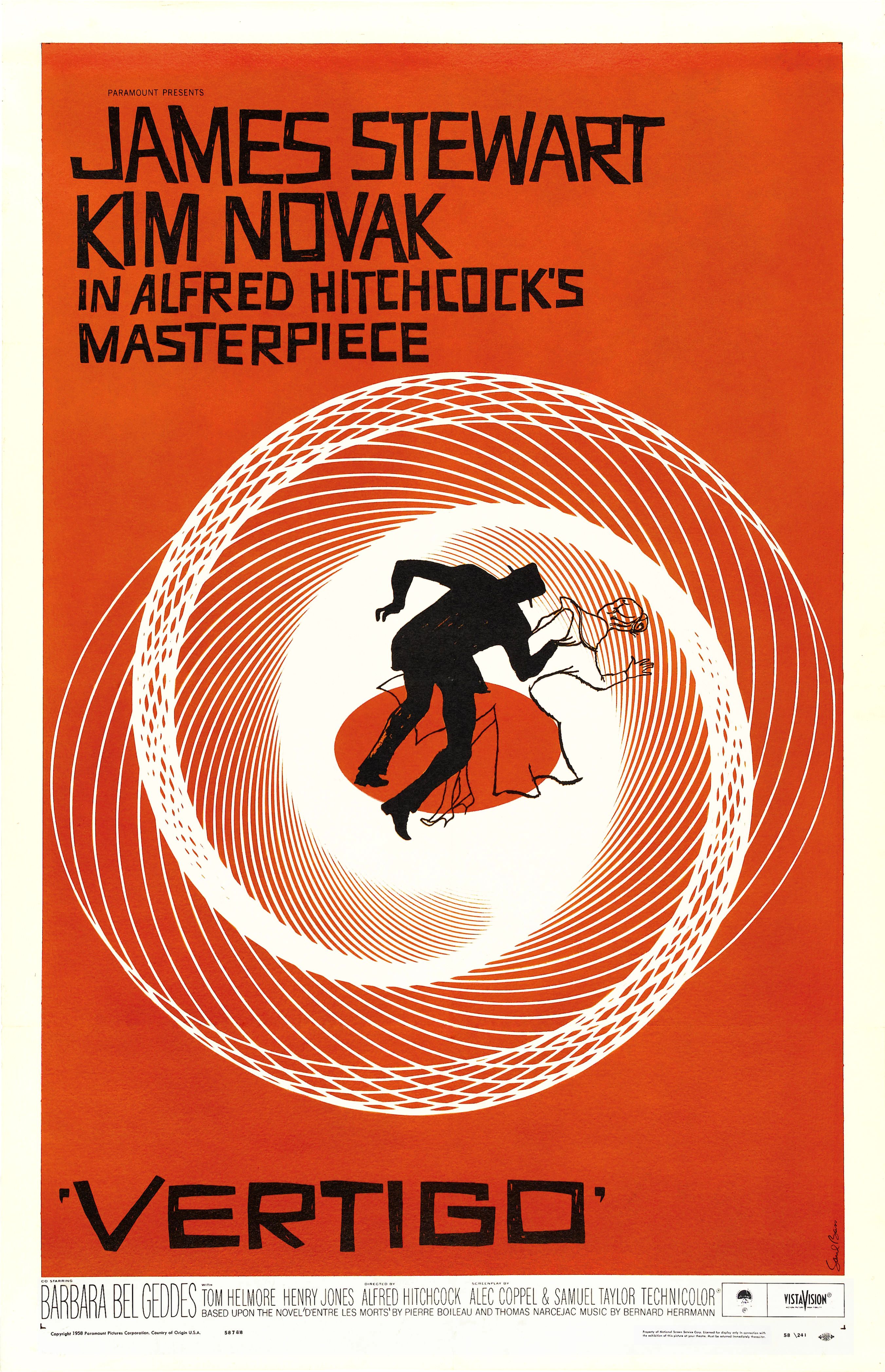

Perhaps the most impactful innovation of them all is present within the opening seconds of Hitchcock's film. Opening credits in most classic Hollywood films were solely perfunctory. They were ostensibly a slideshow version of a playbill for a theater. It wasn't until Saul Bass came along and decided to turn the opening credits into an art form. Bass, a prolific graphic designer of title sequences, movie posters, and corporate logos, collaborated with an impressive lineup of filmmakers, including Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, Otto Preminger, Billy Wilder, and Martin Scorsese. The iconic openings to The Man with the Golden Arm, North by Northwest, and Vertigo were short films in their own right, capturing the tone of the narrative that it preceded. Bass' Vertigo poster distills the film to its core, showing an anonymous figure being sucked into a spiral vortex, evoking Scottie's haunting blend of anxiety and obsession. His finely drawn images on the screen and posters were stitched into the minds of all moviegoers.

Bass was not alone when crafting the title sequence of Vertigo, which depicts a set of eyes staring directly at the viewer. Then, it focuses on one eye, which dissolves into a spiraling vortex of hallucinogenic colors. These transfixing images are accompanied by a sensual, brassy score by composing legend Bernard Herrmann, another frequent Hitchcock collaborator. The opening credits are a distinct interpretation of a hypnotic spell — a lofty concept to realize on screen. When Hitchcock's directing credit appears, the sequence returns to the eye, setting the tone for Scottie's perilous investigation. Everything he will see is a twisted hallucination caused by fear and obsession.

'Vertigo's Title Sequence Was Designed Using Computer Animation

If there is something that seems other-worldly about Vertigo's title sequence, that's because it used computer animation — a first of its time. Bass worked with John Whitney, an animator widely regarded as a pioneer in the computer animation field. Whitney, who worked in an aircraft facility, ingeniously learned to adopt primitive World War II computer technology to enhance the possibilities of digital graphics. Devices that were used to track missiles and bombs could be rendered to create visual art. Before he designed the opening credits of Vertigo with Saul Bass, Whitney already had experience in a creative mold, designing various computer-generated 8mm and 16mm films. His work is indicative of an artist defined by storytelling and not just sheer technical demonstration, as the structure of Vertigo's title sequence immerses the viewer into a story of hypnosis and delusion. Whitney's groundbreaking animation has been preserved by the Academy Film Archive, housing over a dozen of his films in their collection.

From a contemporary perspective, computer graphics from 1958 are expected to look shoddy, but the opening credits of Vertigo remain as timeless as the film's themes and narrative structure. The genius of Whitney’s title sequence design is that it doesn't attempt to resemble high-tech iconography. Instead, the psychedelic aesthetic of the dynamic color palette and spiraling vortex are informed by hand-drawn visuals. John Whitney's animation might be a new-wave medium, but his work in Alfred Hitchcock's masterpiece is classical. It helps that he had another genius in Saul Bass at his disposal, arguably the most minimalist storyteller in the history of cinema through his posters and title sequences. Hitchcock, a maverick of the industry, never settled for complacency. Formally and thematically, the director challenged Hollywood's expectations for cinema. In this case, the unknown world of computer animation debuted under Hitchcock. Needless to say, Vertigo was not the last instance of computer animation in film.

Vertigo is available to stream on Prime Video in the U.S.