Analysis: Hidden and lost weather observations contain hugely valuable information about historical climate variability and changes

By Kevin Healion, Simon Noone, David Smyth, Peter Thorne, Maynooth University; Ciara Ryan, Met Éireann and Ed Hawkins, University of Reading

In 2002, Donald Rumsfeld famously said that "there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know".

But he failed to mention the fourth quadrant of this logic: the unknown knowns, things that we don't know that we know. A case in point of these unknown knowns is many early weather observations that lie unloved in archives, offices and even attics just waiting to be discovered. These early observations can tell us hugely valuable information about historical climate variability and changes, so it is well past time we converted them from unknown knowns to known knowns.

Who collected weather data?

Scientists and mustard-keen amateur observers recorded weather data as far back as the 17th and 18th centuries. The large amount of data that has been gathered since has allowed scientists to build on this record and analyse the global climate throughout that period, and in particular to highlight the warming we have experienced since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. However, a large amount of early data remains out of reach, tucked away in long-forgotten corners, and there is a pressing need to rescue it to shed further light on our changing climate.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Mooney Goes Wild in 2013, the late historical researcher Dinah Molloy on how 18th Century weather records are useful for today's weather patterns

In Ireland, the oldest known weather record includes daily barometer observations and weather remarks for the period January to April 1676, taken from a letter written from an observer in Dublin to the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. It is thanks to these and similar very early meteorological observations that it was possible to create a 305 year monthly rainfall series for Ireland between 1711 and 2016.

During the 19th century, the number of weather stations increased across the island. Early enthusiasts included members of the clergy who operated weather stations at Dunsink in Dublin (1788) and the Armagh observatory (1790). Meanwhile, members of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy set up stations on the grounds of their estates, such as Markree in Co Sligo (1824) and Birr in Co Offaly (1845). By the late 19th century, the UK Meteorological Office had established an official network of stations, which they maintained before the establishment of Met Éireann in 1936.

The missing records

But there are still large collections of Irish weather data that remain undiscovered and the data could be absolutely anywhere. For example, a recent search of the Cork City and County Archives online catalogue led to the discovery of weather reports kept by Bennett's of Ballinacurra, a former malting firm in east Cork.

READ: What historical records tell us about changing climate in Ireland

Collections containing important meteorological data may be packed away in any number of dusty basements, attics or cabinets, waiting to be discovered. Amateur meteorology was popular throughout the late 18th and 19th centuries, and particularly amongst members of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, so there may be a box of meteorological documents which form part of the papers of Anglo-Irish families that are just begging to be revealed.

Religious institutes may also be a source of meteorological data, and not just for Ireland. As many Irish religious institutes have a history of missionary work in regions such as Africa, documents may exist of weather recordings from far and wide. This is of particular importance as meteorological data for regions outside of Europe and North America become increasingly sparse before the 1950s.

Shining a light

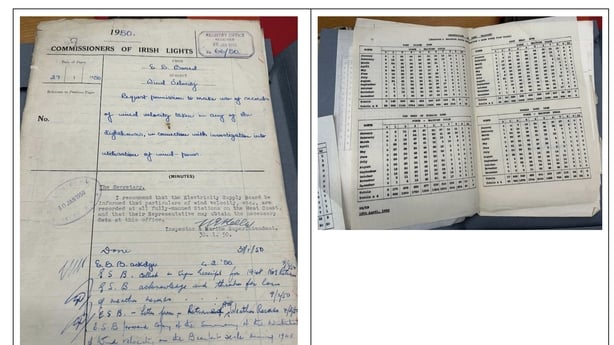

Perhaps the most galling known example of data that has gone AWOL arises from our Irish lighthouses. The Irish Lights archive contains tantalising glimpses of records of weather observations made several times a day for many decades by our lighthouse keepers through fair weather and foul weather. There are records of transactions, instrument replacements and other details in the ledgers in their archives. But, sadly, there is no indication of whether these data have survived, and if so where these data now reside.

These records were clearly available and utilised for a long time. By way of example, the Electricity Supply Board requested meteorological data in 1950 recorded at lighthouses with a view to the viability of offshore wind electricity generation (let's not dwell on the subsequent 75 years of missed opportunities). They were furnished with wind observations from around our coasts.

It is our hope that this collection remains waiting to be unearthed in an archive or premises somewhere in Ireland or Britain. It is not for want of trying across academia and both Met Éireann and the UK Met Office that these remain frustratingly lost. Maybe you or a relative knows some of the history and can help us piece together this jigsaw?

Why finding and preserving these records is important

There is a real risk of data being lost due to the vulnerability of the original paper documents especially if the documents are stored in poor conditions. Rescuing and accessing historical meteorological data furthers our ability to understand historical climate change and to reconstruct past extreme weather events accurately.

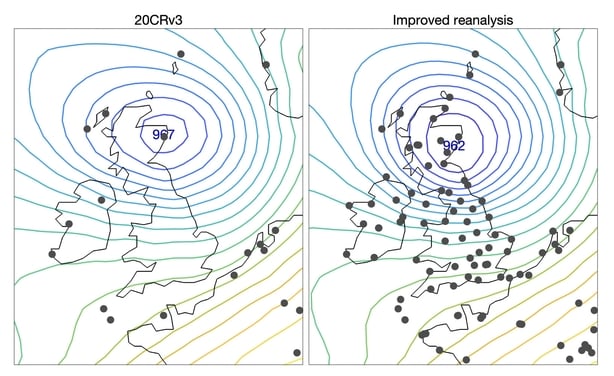

For example, we have been much better able to reconstruct Storm Ulysses, which hit Britain and Ireland in February 1903, by using newly rescued weather observations from the early 20th century. In turn, this enabled a better understanding of the impact a similar storm would have under different future climate scenarios. It is planned to extend this approach to other historical storms, including the Night of the Big Wind in January 1839.

Looking as deeply in the past as we can go, and with as much detail as we can get, helps highlight past variability and trends and provides important context for projections of our possible futures under climate change. These insights are critical if we are to be resilient to future climate events, irrespective of whether they arise by chance or due to human activities.

We close by returning to, and extending, the logic of Donald Rumsfeld: we cannot understand what we do not know. If you are aware of the existence of documents containing meteorological data please make contact with us at the ICARUS Climate Research Centre in Maynooth University, Met Éireann or with other relevant institutions.

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

Kevin Healion is a Research Assistant at the ICARUS Climate Research Centre at Maynooth University. Dr Simon Noone is a Senior Postdoctoral Researcher at the ICARUS Climate Research Centre at Maynooth University. He is a former Irish Research Council awardee. Dr David Smyth is a Post Doctoral Researcher at the ICARUS Climate Research Centre at Maynooth University. Prof. Peter Thorne is IPCC Coordinating Lead Author, Professor in Physical Geography (Climate Change) and Director of the ICARUS Climate Research Centre at Maynooth University. Dr Ciara Ryan is a Climatologist with Met Éireann. She is a former Irish Research Council awardee. Prof Ed Hawins is Professor of climate science at the University of Reading and principal research scientist at the National Centre for Atmospheric Science.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ