100 years of Marcello Mastroianni, the star who never wanted to be a heartthrob

The Cannes Festival is now screening ‘Marcello Mio,’ a film that celebrates the centenary of the great Italian actor and stars his daughter, Chiara. Her Oscar-nominated father spent his career being cast as a ladies’ man, even though the image didn’t match his persona

The iconic Italian actor Marcello Mastroianni (1924-1996) recalled that, when he was offered the chance to star in La Dolce Vita (1960), he asked the director — Federico Fellini — to see the script. What he got was a folder containing a pornographic drawing. Any heartthrob worthy of the label would have reacted with a complicit gesture, or perhaps with another even more ridiculous joke. But Mastroianni turned red to the ears and could barely hide his embarrassment as he asked: “Very interesting, where do I sign?” That film would turn out to be Mastroianni’s great blessing… and his small condemnation.

The movie turned him into a world-renowned star, although it imprisoned him in the archetype of a “ladies’ man.” This didn’t fit either his real-life persona, nor the fictional character he became famous for in La Dolce Vita: a journalist suffering from existential malaise. Still, despite everything — and to his annoyance — the label always pursued him.

In anticipation of the centenary of his birth (which will be celebrated in September), a film about Mastroianni will premiere at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival, which began on May 14 and concludes on May 25. The French-Italian comedy Marcello Mio (2024) will be available in theaters immediately afterwards. Directed by French filmmaker Christophe Honoré, it stars Chiara Mastroianni, the daughter of Marcello and Catherine Deneuve, in the role of an actress who also happens to be the daughter of Marcello Mastroianni and Catherine Deneuve. While going through a rough patch in her life, she decides to adopt the identity and physical appearance of her late father.

In a 2006 interview, 10 years after the actor’s death, Chiara Mastroianni remembered that her father was “a person [filled with] great joy… but who, at the same time, was very melancholic.” She also emphasized his hardworking and humble nature.

This humility, though, could lead him dangerously close to self-hatred. He claimed that his physique lost out when compared to the good looks of Vittorio Gassman, Gérard Philipe, Gary Cooper, or Clark Gable. Despite having probably been the most famous Italian actor since Rudolph Valentino — and despite the fact that he was, undoubtedly, the most critically-acclaimed Italian leading man, with two Best Actor awards at the Venice and Cannes film festivals, two Golden Globes and three Academy Award nominations — he always downplayed his numerous achievements. “I studied the script for a couple of days, I recited my part and it was over,” he summarized, in a joint interview with one of his co-stars, Vittorio Gassman, for the Italian newspaper La Repubblica.

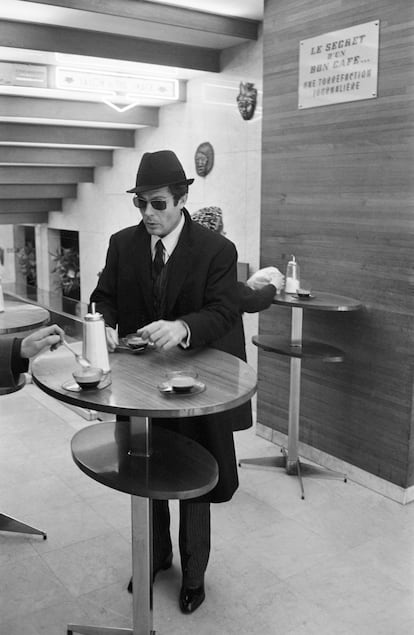

Many actors insist that the public perceive them as being different in each production. To do so, they exhibit an aptitude worthy of a circus performer — supported by the work of makeup artists, hairdressers and accent coaches — to camouflage themselves each time they act. However, Mastroianni always preferred to be recognizable, without hiding his personality behind method acting tricks. “It annoys me [to hear] about actors who study the role for months and months to get into the character, who spend an infinite amount of time in a convent, gaining weight or losing weight to be more fit,” he scoffed, citing Robert De Niro as an example of this phenomenon.

Mastroianni was always Mastroianni. All of his characters shared an attitude that was both intimate and distant. Sometimes he was naive, and on other occasions he was more sly. And this didn’t diminish his ability to plausibly embody personalities that were very foreign to his own. It’s no coincidence that he was chosen to be the alter ego of directors such as Fellini — whom he physically didn’t resemble at all — or Manoel de Oliveira, who was almost 20 years older than Mastroianni when he directed him in Voyage to the Beginning of the World (1997), the actor’s last film. Despite the fact that the pancreatic cancer that ultimately ended his life was already very advanced, his resulting performance was astonishing.

At the service of this task, the Italian had a hyper-expressive face that could go from smiling to being defeated in a split second. He also had his voice, which with a somewhat nasal timbre, coarsened by tobacco, was decidedly atypical for a leading man. These were his main attributes, which also contributed to making him a style icon. Not quite aristocratic and more aimed at the general public, the majority of viewers had no trouble identifying with him. He embodied the Italy of the mid-20th century, with its mixture of provincialism and cosmopolitanism, of atavism and desire for modernity. In the manner of other actors of his generation such as Gassman, Manfredi, Tognazzi, or Sordi, but with greater international reach, he was both a compendium and improvement of his cohort.

Born in 1924 into a modest family (his mother was a typist and his father repaired furniture) in the small town of Fontana Liri, he spent part of his childhood in Turin before the family moved to Rome. There, he graduated as a quantity surveyor and worked as an accountant, while trying to make his way into the world of acting with small roles in film and theater. His talent didn’t go unnoticed by director Luchino Visconti, who in 1949 cast him in the supporting role of Mitch for a production of A Streetcar Named Desire. The play, written by Tennessee Williams, saw Vittorio Gassman play the lead role of Stanley Kowalski.

During the following decade, his acting career was on the rise, although he performed in mostly inconsequential films. That is, until Visconti chose him again — this time as the protagonist — for the romantic drama White Nights (1957), which became his first global success. This was bolstered a year later by the Oscar-nominated Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958), a comedy caper that also featured Gassman. Mastroianni subsequently experienced a takeoff that led him to work with some of the most prestigious Italian directors of the time, such as Mayro Bolognini (Handsome Antonio, 1960), Michelangelo Antonini (The Night, 1961), Pietro Germi (Divorce Italian Style, 1961), De Sica, Scola, Ferreri, Petri, the Taviani brothers and Marco Bellocchio. Then, European and American directors would come knocking, including John Boorman, Theo Angelopoulos, Roman Polanski, Robert Altman, Nikita Mijalkov, Betrand Blier, María Luisa Bemberg, Bruno Barreto, Raúl Ruiz and Manoel de Oliveira.

But the most fruitful meeting was with Fellini, who insisted on recruiting him for La Dolce Vita. This decision went against the opinion of the producers, who would have preferred a Hollywood star such as Paul Newman. However, after an eventful shoot, the film swept the box office and won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, along with four Academy Award nominations (it won for Best Costume Design). At the time, this was an unusual achievement for a non-English language film.

In the classic picture, Mastroianni embodied a modified version of the director and his screenwriter, Ennio Flaianio, both cynics lost in the jungle of modern life. His frolicking scene with Anita Ekberg in Rome’s Trevi Fountain painted him as an updated Mediterranean seducer… an image that he so often rebelled against. Fellini would bring him back in five more films, in which he continued playing increasingly delirious versions of the filmmaker, from 8 ½ (1963) to Interview (1987). Most especially, in Ginger & Fred (1986) he transmitted a frequently imitated but never equaled combination of dignity and pathos.

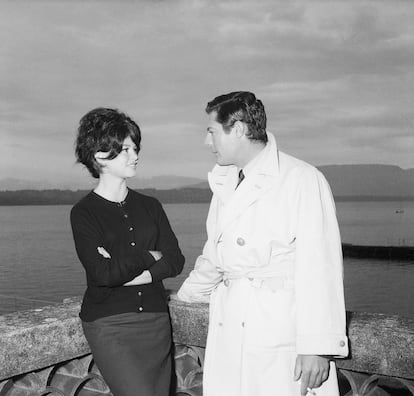

To summarize the reasons why American and global culture embraced Mastroianni as the epitome of Italianness, two factors can be cited: La Dolce Vita and Sophia Loren. He and the most famous Italian film actress in history shared the marquee a total of 14 times. In about a third of these films, they played a couple on screen, always denying that they had had an affair in real life (although the rumor about it was insistent). The first of these was Too Bad She’s Bad (1955), by Alessandro Blasetti. Loren stated that, when she was offered a role alongside him, she blindly accepted it because she was sure that things would turn out well. It didn’t always happen exactly that way but their best joint performances were peak moments of grace and charisma. Marriage Italian Style, based on the play by Eduardo de Filippo, stands out, as does A Special Day (1977), a bittersweet story about the meeting of two losers, who survive the adverse circumstances that have befallen them as best as they can.

Mastroianni chose to play the antihero on numerous occasions, which is why he specialized in passive, defeated, insane, misplaced, or impotent men (during the production of Handsome Antonio, he took his job so seriously that, apparently, it caused him real-life problems of sexual performance during the filming period). Going beyond the hearthrob or Latin lover, his personality, both on and offscreen, is closer to another very Italian archetype: that of the mammone, a momma’s boy, or a perpetual big boy whose Oedipal problems determine his relationships with women. Mastroianni never divorced his wife, Flora Carabella (an actress he met on the set of A Streetcar Named Desire and with whom he had his eldest daughter, Barbara), although they separated in 1970. That was when he began a relationship with Deneuve, which lasted a few years. Chiara Mastroianni would be born from this relationship.

Before this, he had had an even more short-lived romance — and one that ended painfully for him — with Faye Dunaway. He also had a young love story with Silvana Mangano, from when they were both aspiring actors. And, in his last days, he acknowledged that, at one point in his life, he had an unreciprocated crush on Claudia Cardinale, another of the recurring co-stars in his career.

The director Anna Maria Tatò, who made the documentary about his life, Marcello Mastroianni: I Remember, Yes I Remember (1997), was his partner for almost two decades. Upon the actor’s death, in 1996, disagreements between Tatò, Deneuve and Carabella became evident. This included some difficult episodes, such as the celebration of different funerals in Rome and Paris, with different religious ceremonies (although EL PAÍS reporter Maruja Torres recalls that Mastroianni was an avowed atheist). Ultimately, the public disclosure of a clause in his will left the rights to his image in the hands of Tatò until her death, which occurred in 2022. Hence, it’s reasonable to assume that Marcello Mio, which now stars Chiara Mastroianni and is crafted in the actor’s own image, couldn’t have been filmed before.

Like the new film, other initiatives are commemorating the 100 years since the iconic actor’s birth. In Italy, the Mastroianni 100 Committee has been created to promote them. Various public tributes and film series have already been announced, which have been compiled in a book.

In life, however, Mastroianni wasn’t much of a fan of compliments and ceremonies. “At a certain point, they start calling you a teacher,” he lamented. “A teacher of what?”

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition