Features

An encounter with James Bond creator Ian Fleming in his newspaper days

“I knew the father of 007”

(Excerpted from Selected Journalism by HAJ Hulugalle)

Many journalists develop what may be called the grasshopper mind. In their work it is necessary to hop from one subject to another. If at the end of their lives they have little to show for their pains, they may have bitter sweet memories stored up squirrel-wise of unusual people and events.

There is of course, a certain vanity in being able to say, “Oh yes, I knew Mahatma Gandhi” or I saw Bradman making his first century at Lords.” Such a display of self-esteem may even provoke the reaction if unexpressed, “So what.” There is no reason why anyone else should be interested. But not always. If we have a hero or a favourite, we like to listen to someone who has met and talked with him.

So Browning’s – Ah, did you once see Shelley plain, And did he stop and speak to you And did he speak to you again? How strange it seems and new. I recall a sentimental journey made with a friend in search of the house near La Spezia to which Shelley’s body was brought after the drowning.

Meeting or seeing unusual or famous people is often a matter of chance. On June 4, 1946, twenty years ago that is, I was a guest at dinner of Lord and Lady Kemsley, with several other delegates to the Empire Press Conference of that year. The company included many interesting men, but I was particularly attracted to the one who sat on my right. He was Ian Fleming.

Perhaps the name rings a bell for you? He was Manager of the Foreign Department of the Kemsley Newspapers. In conversation I found that he was the brother of Peter Fleming, whose articles I had read and whose wife, the beautiful Celia Johnson, I had seen on the London stage 15 years earlier.

Ian Fleming was not then the famous man he was to become as the fabulous author of the James Bond books.

He did not in fact start writing them till five or six years after, but was then negotiating to buy the house in Jamaica where he wrote most of them. The other bit of gossip I heard about him then was that he was often seen about with Lady Rothermere, the wife of the newspaper tycoon.

Anne Rothermere (nee Charteris) was previously the wife of Lord O’Neill, who was killed in World War II. Fleming married her, after the divorce from Rothermere, in 1952. The union produced not only a son but a dozen books which have sold more copies than the Bible and the works of William Shakespeare, and earned as much money as any author at present, or in the future, is likely to earn.

After our dinner at Chandos House, Lord Kemsley’s London home, I wrote to Ian Fleming suggesting that we might keep up our connection by my representing his group of newspapers in Ceylon. He gladly agreed. I came across recently, his letter and the table plan of the Chandos House dinner. But I lost interest in the Kemsley newspapers, which included the London Sunday Times. I was already correspondent of The Times, an assignment which was more remunerative and enjoyable.

The link with Printing House Square was further strengthened by a long standing friendship with Iverach MacDonald then the Diplomatic Correspondent and now the Diplomatic Editor of The Times.

It was as already hinted, his marriage with Anne Rothermere that made Ian Fleming a prolific author. She became a political hostess and had a salon during the season in London. James Bond provided the grist for the mill.

As Fleming himself said, “I invented him to soothe my nerves before the appalling business of getting married in 1952. It was rather a dramatic step for a confirmed bachelor to take, and I created Bond to sort of insulate myself against the shock.”

Fleming died in August 1964. As indicated already, I met him 18 years earlier. He was then a tall, lean man, exuding charm and well-informed. He had been educated in England. Germany and Switzerland and acted as correspondent of The Times in Russia.

Ian was one of four sons of a Conservative MP, Major Valentine Fleming, who was killed in World War I at the age of 32, leaving a lot of money and a young widow to bring up the boys. Major Fleming’s father, who had been a Dundee bookkeeper, made a fortune by starting investment trusts in Scotland and left a quarter of a million pounds.

Mrs. Valentine Fleming moved in society and had friends as well known as Augustus John, the painter, and the Marquis of Winchester. The Parsi socialite Bapsy Pavry, married the Marquis when he was about 90. Mrs. Fleming initiated legal action to separate him from her on the grounds that he was not in a condition to decide for himself. Miss Pavry was the first Oriental to become a British Marchioness and often visits the House of Lords, I am told.

A few weeks after I met Ian Fleming I was in Paris as an accredited correspondent to the Press Conference after World War II, held at the Luxembourg Palace. On the first day of the conference by mistake on the part of the usher I was placed in the distinguished strangers’ gallery. Those around me were Ho Chi Minh, later to become the ruler of North Vietnam, Mrs. Clement Attlee and on my right, Bapsy Pavry. She was intelligent and charming.

Proximity to the great is seldom rewarding except to the curious. A journalist enjoys his work to the extent to which his bump of curiosity is developed. Like St. Paul’s Athenians, journalists are accustomed always to tell or hear some new thing. I found it helpful to have seen or heard famous men – Lloyd George, Churchill, Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald – they were always in the news, their names always cropping up.

To have known a writer does not perhaps help in the same way. I have enjoyed the few books of Ian Fleming that I have read, but have not wanted to read all his books which have now sold over thirty million copies. Life is too short. But though he was no Shelley, I am glad that I saw the man who was to become the greatest one man factory of our time. It was a great lark to look back on.

(First published in 1966)

Features

A fairy tale, success or debacle

Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement

By Gomi Senadhira

senadhiragomi@gmail.com

“You might tell fairy tales, but the progress of a country cannot be achieved through such narratives. A country cannot be developed by making false promises. The country moved backward because of the electoral promises made by political parties throughout time. We have witnessed that the ultimate result of this is the country becoming bankrupt. Unfortunately, many segments of the population have not come to realize this yet.” – President Ranil Wickremesinghe, 2024 Budget speech

Any Sri Lankan would agree with the above words of President Wickremesinghe on the false promises our politicians and officials make and the fairy tales they narrate which bankrupted this country. So, to understand this, let’s look at one such fairy tale with lots of false promises; Ranil Wickremesinghe’s greatest achievement in the area of international trade and investment promotion during the Yahapalana period, Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (SLSFTA).

It is appropriate and timely to do it now as Finance Minister Wickremesinghe has just presented to parliament a bill on the National Policy on Economic Transformation which includes the establishment of an Office for International Trade and the Sri Lanka Institute of Economics and International Trade.

Was SLSFTA a “Cleverly negotiated Free Trade Agreement” as stated by the (former) Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Malik Samarawickrama during the Parliamentary Debate on the SLSFTA in July 2018, or a colossal blunder covered up with lies, false promises, and fairy tales? After SLSFTA was signed there were a number of fairy tales published on this agreement by the Ministry of Development Strategies and International, Institute of Policy Studies, and others.

However, for this article, I would like to limit my comments to the speech by Minister Samarawickrama during the Parliamentary Debate, and the two most important areas in the agreement which were covered up with lies, fairy tales, and false promises, namely: revenue loss for Sri Lanka and Investment from Singapore. On the other important area, “Waste products dumping” I do not want to comment here as I have written extensively on the issue.

1. The revenue loss

During the Parliamentary Debate in July 2018, Minister Samarawickrama stated “…. let me reiterate that this FTA with Singapore has been very cleverly negotiated by us…. The liberalisation programme under this FTA has been carefully designed to have the least impact on domestic industry and revenue collection. We have included all revenue sensitive items in the negative list of items which will not be subject to removal of tariff. Therefore, 97.8% revenue from Customs duty is protected. Our tariff liberalisation will take place over a period of 12-15 years! In fact, the revenue earned through tariffs on goods imported from Singapore last year was Rs. 35 billion.

The revenue loss for over the next 15 years due to the FTA is only Rs. 733 million– which when annualised, on average, is just Rs. 51 million. That is just 0.14% per year! So anyone who claims the Singapore FTA causes revenue loss to the Government cannot do basic arithmetic! Mr. Speaker, in conclusion, I call on my fellow members of this House – don’t mislead the public with baseless criticism that is not grounded in facts. Don’t look at petty politics and use these issues for your own political survival.”

I was surprised to read the minister’s speech because an article published in January 2018 in “The Straits Times“, based on information released by the Singaporean Negotiators stated, “…. With the FTA, tariff savings for Singapore exports are estimated to hit $10 million annually“.

As the annual tariff savings (that is the revenue loss for Sri Lanka) calculated by the Singaporean Negotiators, Singaporean $ 10 million (Sri Lankan rupees 1,200 million in 2018) was way above the rupees’ 733 million revenue loss for 15 years estimated by the Sri Lankan negotiators, it was clear to any observer that one of the parties to the agreement had not done the basic arithmetic!

Six years later, according to a report published by “The Morning” newspaper, speaking at the Committee on Public Finance (COPF) on 7th May 2024, Mr Samarawickrama’s chief trade negotiator K.J. Weerasinghehad had admitted “…. that forecasted revenue loss for the Government of Sri Lanka through the Singapore FTA is Rs. 450 million in 2023 and Rs. 1.3 billion in 2024.”

If these numbers are correct, as tariff liberalisation under the SLSFTA has just started, we will pass Rs 2 billion very soon. Then, the question is how Sri Lanka’s trade negotiators made such a colossal blunder. Didn’t they do their basic arithmetic? If they didn’t know how to do basic arithmetic they should have at least done their basic readings. For example, the headline of the article published in The Straits Times in January 2018 was “Singapore, Sri Lanka sign FTA, annual savings of $10m expected”.

Anyway, as Sri Lanka’s chief negotiator reiterated at the COPF meeting that “…. since 99% of the tariffs in Singapore have zero rates of duty, Sri Lanka has agreed on 80% tariff liberalisation over a period of 15 years while expecting Singapore investments to address the imbalance in trade,” let’s turn towards investment.

Investment from Singapore

In July 2018, speaking during the Parliamentary Debate on the FTA this is what Minister Malik Samarawickrama stated on investment from Singapore, “Already, thanks to this FTA, in just the past two-and-a-half months since the agreement came into effect we have received a proposal from Singapore for investment amounting to $ 14.8 billion in an oil refinery for export of petroleum products. In addition, we have proposals for a steel manufacturing plant for exports ($ 1 billion investment), flour milling plant ($ 50 million), sugar refinery ($ 200 million). This adds up to more than $ 16.05 billion in the pipeline on these projects alone.

And all of these projects will create thousands of more jobs for our people. In principle approval has already been granted by the BOI and the investors are awaiting the release of land the environmental approvals to commence the project.

I request the Opposition and those with vested interests to change their narrow-minded thinking and join us to develop our country. We must always look at what is best for the whole community, not just the few who may oppose. We owe it to our people to courageously take decisions that will change their lives for the better.”

According to the media report I quoted earlier, speaking at the Committee on Public Finance (COPF) Chief Negotiator Weerasinghe has admitted that Sri Lanka was not happy with overall Singapore investments that have come in the past few years in return for the trade liberalisation under the Singapore-Sri Lanka Free Trade Agreement. He has added that between 2021 and 2023 the total investment from Singapore had been around $162 million!

What happened to those projects worth $16 billion negotiated, thanks to the SLSFTA, in just the two-and-a-half months after the agreement came into effect and approved by the BOI? I do not know about the steel manufacturing plant for exports ($ 1 billion investment), flour milling plant ($ 50 million) and sugar refinery ($ 200 million).

However, story of the multibillion-dollar investment in the Petroleum Refinery unfolded in a manner that would qualify it as the best fairy tale with false promises presented by our politicians and the officials, prior to 2019 elections.

Though many Sri Lankans got to know, through the media which repeatedly highlighted a plethora of issues surrounding the project and the questionable credentials of the Singaporean investor, the construction work on the Mirrijiwela Oil Refinery along with the cement factory began on the24th of March 2019 with a bang and Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and his ministers along with the foreign and local dignitaries laid the foundation stones.

That was few months before the 2019 Presidential elections. Inaugurating the construction work Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe said the projects will create thousands of job opportunities in the area and surrounding districts.

The oil refinery, which was to be built over 200 acres of land, with the capacity to refine 200,000 barrels of crude oil per day, was to generate US$7 billion of exports and create 1,500 direct and 3,000 indirect jobs. The construction of the refinery was to be completed in 44 months. Four years later, in August 2023 the Cabinet of Ministers approved the proposal presented by President Ranil Wickremesinghe to cancel the agreement with the investors of the refinery as the project has not been implemented! Can they explain to the country how much money was wasted to produce that fairy tale?

It is obvious that the President, ministers, and officials had made huge blunders and had deliberately misled the public and the parliament on the revenue loss and potential investment from SLSFTA with fairy tales and false promises.

As the president himself said, a country cannot be developed by making false promises or with fairy tales and these false promises and fairy tales had bankrupted the country. “Unfortunately, many segments of the population have not come to realize this yet”.

(The writer, a specialist and an activist on trade and development issues . )

Features

Deconstructing Ravi

By Uditha Devapriya

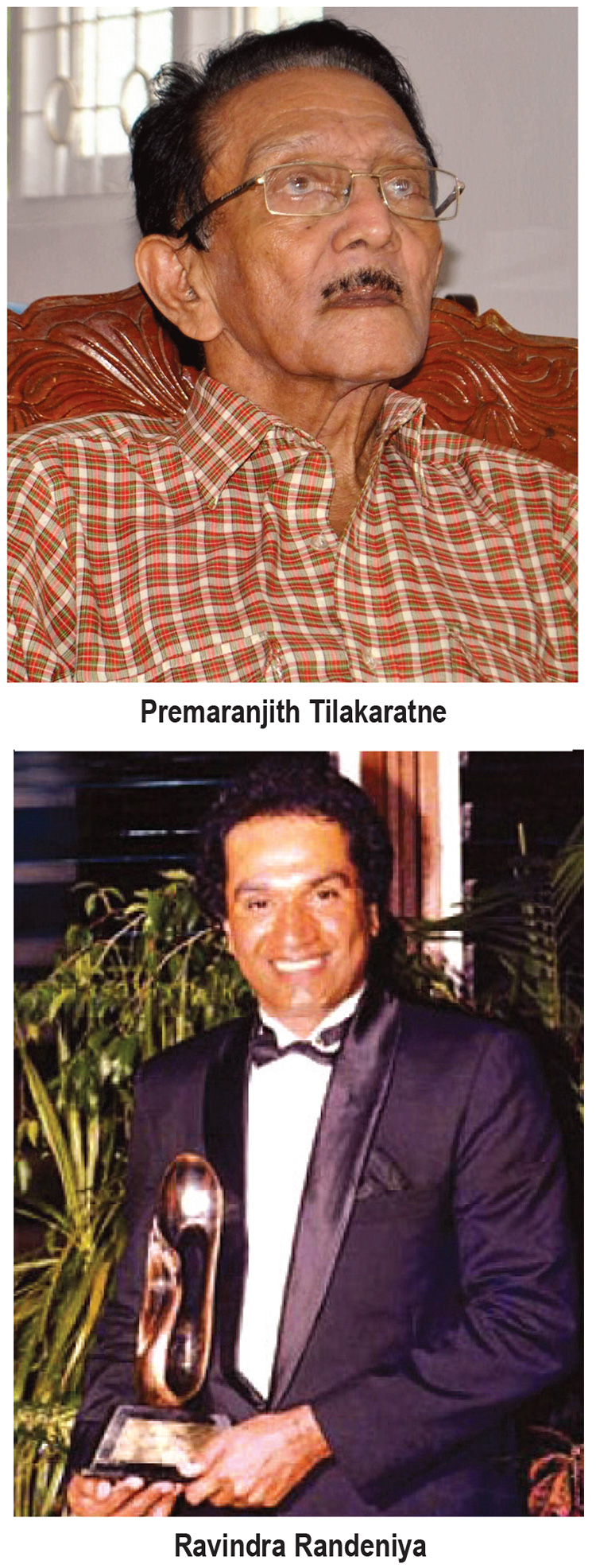

A book on Ravindra Randeniya was long incoming, and now we have two. Full disclosure: I am the author of one of them. Gamini Weragama, arguably the most knowledgeable and reputed film critic writing in Sinhala today, has authored the other.

A book on Ravindra Randeniya was long incoming, and now we have two. Full disclosure: I am the author of one of them. Gamini Weragama, arguably the most knowledgeable and reputed film critic writing in Sinhala today, has authored the other.

Weragama’s book was published by Sarasavi, mine by FastADS. Both were launched at a ceremony at the BMICH last Wednesday, June 5. The event, excellently put together by a hardworking, passionate team led by Dr Ranga Kalansooriya, witnessed a galaxy of actors, directors, critics, writers, MPs, even the president and prime minister. My friend Indunil put it in perspective: “the whole of Sinhala cinema was there that night.”

Ravindra is Ravi aiya to his colleagues, contemporaries, and juniors. He is by far the most distinguished, reputable actor alive in Sri Lanka. This is not to underplay or ignore any criticism we can make of him. Yet, as far as Sri Lankan actors go, he remains unmatched in the dazzling range and complexity he has embraced in role after role.

But there is more to Ravindra than the films he has been in and the roles he has taken on. Much more. To assess his career more carefully, I believe we need to look at him through a different lens and prism, specifically a sociohistorical one. This is the perspective I have adopted in parts of my book, but it is one which requires a radically different conception of actors and their place in our society.

Any assessment of Randeniya must, I think, begin from the fact that he came of age in 1956. That year has become pivotal for reasons which warrant a separate essay. More than anything, it launched the careers of an entirely different generation of artistes, including playwrights, filmmakers, musicians, and dancers.

While S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike was spreading the gospel of Sinhala Only throughout the country, Ravindra Randeniya was taking part in a Fifth Standard production of Sigiri Kashyapa at his school, St Benedict’s College, Kotahena. Incredibly, it was the only stage production he took part in at school. Indeed, he would not act in any production of any sort until more than a decade later, when he joined the Lionel Wendt Theatre Workshop. Why so? Because, in his own words, “I was more interested in literature than in theatre.”

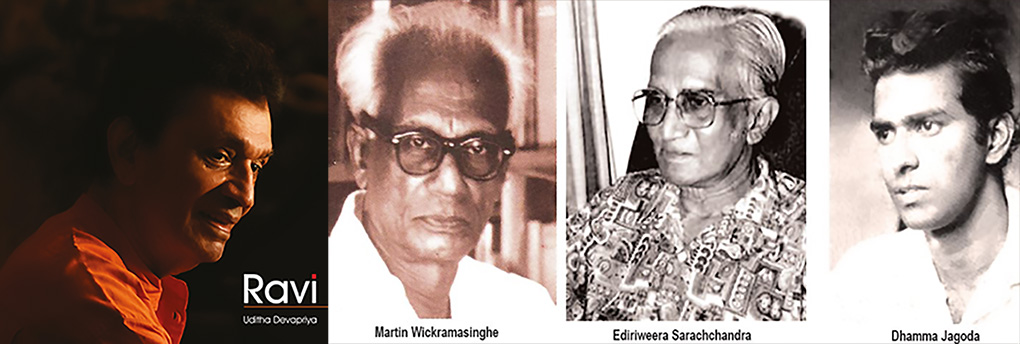

A highly literate student, Ravindra immersed himself in the literature of his time, reading everyone from Martin Wickramasinghe to Siri Gunasinghe to Gunadasa Amarasekara to Mahagama Sekara. Though he watched films, he did so only occasionally, and was limited to standard Hollywood and Bollywood fare. Over time, he saw himself as a litterateur, though his larger ambition was to become a doctor.

For better or worse, Ravindra could not pursue his medical ambitions. He then got down to working for his father. By now, he was living through a completely different time. The Sinhala theatre was undergoing a revival, as was the cinema. Spurred on by the likes of Ediriweera Sarachchandra and Lester Peries, these mediums became more accessible to the Sinhala speaking masses, leading to the formation of independent theatre collectives which went against the grain and questioned accepted artistic conventions.

Ravindra’s entry into the cinema was preceded by three long but fateful years at the Lionel Wendt Theatre Workshop. The Workshop was a product of its time, and its impact on the country’s cultural community was considerable. However, for some reason, it has escaped the attention of critics. To understand its relevance for Ravindra, we ought to delve into the changes that were sweeping through Sri Lanka at that point.

In the 1950s and 1960s, a number of playwrights and theatre practitioners made their way to Western countries, through grants and scholarships. One of the first of these was Henry Jayasena, who travelled to both Russia and England. Gunasena Galappatti, who introduced García Lorca to Sri Lankan audiences, won a Fulbright Scholarship to the US, where he came under the influence of Uta Hagen and the Actors’ Studio. This was around the time that two other pioneering intellectuals – Gananath Obeyesekere and J. B. Disanayake – secured the Fulbright. The impact of these scholarships and exchange programmes on Sri Lanka’s cultural trajectory was massive, though it has never been researched in full.

Freed from the conventions of their predecessors, these dramatists experimented in different artistic forms and idioms. They fostered the growth of a bilingual cultural elite in Sri Lanka. They also attracted another group of playwrights, who hailed from a Sinhala-speaking lower middle-class and had found jobs in the country’s administrative service. Many among this group went on to form independent theatre collectives, the most popular of which was Sugathapala de Silva’s Ape Kattiya, along with Premaranjith Tillekeratne’s 63 Kandayama – a breakaway faction from Ape Kattiya – and G. D. L. Perera’s Kala Pela.

These playwrights were driven by an almost visceral aversion to Sarachchandra’s mixture of stylised and realist theatre. Premaranjith, in particular, took a strong dislike to what he saw as the great man’s opposition to Western theatrical forms. “When I once played for him a recording from West Side Story,” he related to me, “he just winced and said, ‘What is this cacophony?’” Such encounters persuaded Tillekeratne and his peers that the country was in need of a different conception of theatre and art.

Of course, to limit the Lionel Wendt Theatre Workshop to the efforts of these innovators alone would be to credit one group, when there was in fact several other groups involved in its establishment and founding. Sarachchandra himself became a founding figure, as did scholars like Percy Colin-Thomé, A. J. Gunawardena, and Wimal Dissanayake, together with artistes from other fields, like Chitrasena, Manjusri, and Amaradeva.

Looming above all of them was Dhamma Jagoda. A dramatist, connoisseur of the arts, and fiery radical, Jagoda was instrumental in formulating a syllabus for the Workshop. Together with Harold Peiris, he came up with a curriculum which could impart the best and the latest in Western, European, and Asian theatre to students.

Jagoda himself had travelled abroad on a grant. In 1967-1968, following his production of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire – Sinhalised as Ves Muhunu and starring the likes of Roma de Zoysa, Rukmani Devi, and Sunethra Sarachchandra – he had secured a scholarship from the British Council. Visiting more than 15 countries, and ending up in New York, he had not just met Lee Strasberg but also talked with Marlon Brando.

Jagoda was tempestuous and unpredictable, a Picasso-like genius who resorted to the most unconventional methods. “He gave up everything to dedicate himself to teaching,” his wife Manel, who became involved in the Workshop, first as a student and then as an organiser, recalls. Ravindra’s senior by four years, he mentored the budding actor well. “He was an almost fanatical stickler for time,” Ravindra remembered him. “Once I got five minutes late, and he put me out, telling me that we should be five minutes early.”

If these anecdotes and encounters put Ravindra in the background, that is because Ravindra was a product of his times, and there is no use deconstructing him without deconstructing the period he hailed from. Moreover, Ravindra’s forays into the cinema were conditioned by his experience in the theatre, for at least two reasons.

First, the Workshop made him more receptive to the intricacies of acting: he had signed up originally for backstage work, among other subjects, but Dhamma pulled him into acting classes. “It made me more sensitive to the art of acting, which I had not seen as an art until then.” Second, because it involved the leading cultural figures of the day, the Workshop attracted the interest of filmmakers, actors, and critics. By 1972, when he passed out with a Diploma, Ravindra was hence getting offers from the likes of Lester Peries.

All these points have been laid bare in the two books on Ravindra. The man’s achievements cannot be emphasised enough. Ravindra redefined what it meant to be an actor in Sri Lanka. The stage had already been set for him by Gamini Fonseka, Joe Abeywickrema, and Tony Ranasinghe. Ravindra continued their legacy while breaking with their tradition: in effect, by cultivating a range almost unparalleled among his predecessors.

It is thus wrong to pigeonhole Ravindra into one type of role and to overlook his diversity. That diversity is what makes the man tick. The Lionel Wendt Theatre Workshop, and the developments of the 1960s, had a huge say on his evolution. It would be wrong to overlook those developments too. This is the point of our books.

Uditha Devapriya is a writer, researcher, and analyst who writes on topics such as history, art and culture, politics, and foreign policy. He is one of the two leads in U & U, an informal art and culture research collective. He can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

Rising election fever; feminine concerns and help

There really is no other country like Sri Lanka! Here, Cassandra’s meaning is different to that which the slogan is meant to convey as used by the Sri Lanka Tourism. As opposite as the South Pole is to the North Pole. SL is conveyed to be joyfully serendipitous, giving tourists much variety, beauty and pleasant surprises. What Cassandra means is that SL is unparalleled in its decadence, corruption, stupidity, absurdity, inconsistency and laying stress on matters unimportant while ignoring the really significant and relevant. And now most citizens are desperate while all are dissatisfied and devoid of hope.

There really is no other country like Sri Lanka! Here, Cassandra’s meaning is different to that which the slogan is meant to convey as used by the Sri Lanka Tourism. As opposite as the South Pole is to the North Pole. SL is conveyed to be joyfully serendipitous, giving tourists much variety, beauty and pleasant surprises. What Cassandra means is that SL is unparalleled in its decadence, corruption, stupidity, absurdity, inconsistency and laying stress on matters unimportant while ignoring the really significant and relevant. And now most citizens are desperate while all are dissatisfied and devoid of hope.

Cassandra elucidates. What need we, the citizens, and the government, particularly, concentrate on now at present times? Turning the economy around? Attempting to pay off debts? Easing the burden of the disadvantaged people, who account for around 30% to 40% of the population? We Ordinaries have tightened our belts. Those in government and particularly Parliamentarians are concentrating on getting duty-free luxury car permits and insurance till they and their extensive families die off.

To Cass a very relevant factor that makes us a land like no other is the concentration of all on elections. The questions asked from the end of last year were and are whether elections will be held; which election will be held first, and who is contesting the presidential election. Thus, the news relayed by TV channels is 80% election-related and 20% on the miseries in this country.

In sharp contrast, take Britain. On May 22, PM Rishi Sunak announced general elections in Britain will be conducted on July 4. How much time between official announcement and event? 44 days; one month and 14 days; 6 weeks. As short as that. And in this negatively unique country almost a year before an imagined election, OK, hoped for election talk was loud, persistent and unclear about the event. Even today, almost six months later, we are not sure which election will be held and when exactly.

The Parliament of Britain is considered the mother of all parliaments. The British manage without a written constitution but follow rules, regulations, customs as practised down the years. We meddle with our Constitution often and now have 22 Amendments.

All these conjectures got Cass humming a tune from the musical of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. “Why cannot a woman be more like a man?” Cass echoes GBS: Why cannot Sri Lanka be more like Britain or any other civilised nation, notwithstanding the former’s boast of a 2500-year-old cultural heritage, et al? This is another proof that SL is like no other country – in its perversity and foolishness. By the time elections are definitely announced and dates fixed, we Ordinaries will be delirious.

Women’s needs

Two articles in the previous week’s The Island papers dealt with the need for formal teaching of personal hygiene to teenage girls and making their needs during their monthly periods easily and cheaply available. Taboos are fast disappearing and people are not stupidly hush hush about menstruation.

A certain organisation thoughtfully distributed packs of essentials like sanitary pads, soap, etc., to girls in remote villages, to ease this burden which curtails their normal lives severely each month and prevents school attendance too.

This compels Cassandra to narrate the brave help given by an Indian small-time businessman to women: first his wife, then to others in his village area which caught on subcontinent-wise.

Arunachalam Muruganantham, son of poor handloom weavers, realized his wife used old rags since she could not afford sanitary pads. He researched in 1998 and found that only ten to twenty percent of all Indian females could afford proper menstrual hygienic products.

He decided to produce low cost pads and experimented with his wife as a guinea pig. Unsuccessful. He had to use and discard different materials to cover the cotton. He invented a simple machine to turn out the pads and managed to get university girls to give him feedback.

By now he had earned some derisive nicknames too. When guinea pigs decreased, he experimented with him wearing a bag of animal blood. However, finally he succeeded in turning out sanitary pads cheap and helped others to make machines or sold his which cost US$ 950 against an imported machine costing $500,000.

He started a sort of revolution in his country by selling 1,300 machines to 27 states and recently started exporting to developing countries, and thus much of rural India had their girls going through the days of the month with no severe interruptions and trepidation. He was named by Time Magazine in 2014 as one of 100 of the world’s most influential persons.

Cass’ input here is about another not much talked of, actually hidden suffering of girls and women in Sri Lanka. That is harassment, usually sexual, in public places and public transport. Cass need not elaborate on this. She herself has suffered in Kandy crowds during the early days of the Esala Perahera; in buses, in cinemas.

Then she adopted the ruse of carrying a pin and a stern face and a shout, never mind the consequences. She well remembers the rage she got into on one of her early morning walks, when she saw a three-wheeler driver parked near a small girls’ school exhibiting himself.

The contrast between the man’s vileness and the little girls’ innocence sent her screaming at the man. Fortunately for her, he fled in his vehicle. These types are usually funk sticks as we used to name them. But one never knows.

If a girl is being harassed by a man with his hands or body, she will usually not be supported by others in the bus, least of all the driver and conductor. This last named will tell her to get down and travel by car.

Experiences in countries like the Philippines, where Cass roamed the cheapest of markets with stunningly beautiful Rohini from New Delhi had not one jab, push, grasp nor fumble. A market in Delhi was horrendous. Maybe where men do not harass women is where they are not frustrated; prostitution freely available and often legalised.

To a young girl, protectively nurtured in a safe milieu, such harassment can be traumatic. I witnessed this recently. A driver who comes to help Cass got a call from his teenage daughter. She told him how she was ‘tortured’ by an older man on a bus. The father got enraged. “I will kill that man with my hare hands”, he shouted, asking her to photograph him. Too late and fortunate, since in his anger he would have traced the miscreant and committed murder.

Cass does not intend story telling. She asks you, her readers, what should be done to reduce if not curb and wipe out this crime. The police to patrol public transport; vigilantes to be recruited? It is the DUTY of the government, especially the relevant ministries, to make it safe for girls and women to get about their work.

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoMullenLowe Group Sri Lanka appoints top aviation professional Lakshika Gunatilake to head LowePublic

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days ago2023 GCE Advanced Level results released

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoBrydon Carse given three-month ban over betting breaches

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoCEO of Kelani Valley Plantations admitted to hospital following workers’ protest

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoPacked schedule for top athletes as deadline nears for Olympic qualification

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoDecide correctly to weed out corrupt politicians at least this time round!

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoIs defunding tertiary education really the need of the hour?

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoUS: Choice between hawk and felon