Author’s note: this article was originally written before Roger Corman’s passing. It was, of course, not intended as a piece to honor his death, but it has become so. Rest easy, Roger. Thank you for everything.

It’s difficult to overstate just how significant Roger Corman is in the annals of American cinema history. Martin Scorsese, Bruce Dern, Francis Ford Coppola, Joe Dante, James Cameron, Charles Bronson, Dennis Hopper, and more – their film careers were all nurtured in one way or another by Corman. Beyond the list of prolific filmmakers who started under his wing, Corman’s own filmography is just as noteworthy. For more than fifty years, Corman’s work spanned genres and styles, and its influence remains as strong as ever.

The film that perhaps best encapsulates Corman’s maverick approach, cultural impact, and sense of humor is 1960’s The Little Shop of Horrors. By the time of Little Shop’s production in 1959, Corman had already been integral to the genesis of American International Pictures (AIP). When the company was formed in 1954 as the American Releasing Corporation (ARC), it had no films to its name and almost no money in the bank.

Corman gambled and chose ARC to distribute a thriller he’d produced called The Fast and the Furious, the title of which he eventually licensed to Universal in 2001 for their ongoing franchise. Corman’s distribution deal meant he was paid upfront, allowing him a quick start on more pictures to properly establish himself as a producer/director.

Corman subsequently produced and directed several films for AIP, allowing them to get off the ground. In turn, AIP became similarly integral to the careers of Scorsese, Bronson, and others. For example, Scorsese’s second film (1972’s Boxcar Bertha) was AIP-financed and Corman-produced.

“Fast and furious” also describes Corman’s work ethic. For the low-budget exploitation films that made up AIP’s bread and butter, Corman took about a week to make each of them, blitzing through multiple setups a day. The same approach held true for films he made with other outfits, and Corman always tried to tap into the latest headlines for maximum effect.

For example, when Corman made War of the Satellites for Allied Artists, it came on the heels of Sputnik 1’s launch and the subsequent American panic over Soviet missile-satellite technology. Corman immediately went to the head of Allied Artists and asked for $70,000, promising that the film would be in theatres within seven weeks.

Seven weeks is perhaps a bit of sensationalism in Corman’s recollection, but it is true that Sputnik 1 was launched in October 1957, War of the Satellites was in production by December, and it was released by May 1958—just as Sputnik 3 captured headlines once again.

Around the same time, Corman had set up his own production and distribution company, The Filmgroup. Having made a horror comedy for AIP called A Bucket of Blood in 1959, Corman wanted to do another. A Bucket of Blood had been shot in five days, and its success encouraged Corman to beat his own record. So, on leftover sets and shot over two days and a night, Corman produced and directed The Little Shop of Horrors for The Filmgroup.

It’s a tale as old as time. Boy likes girl. Boy grows carnivorous plant. Carnivorous plant demands blood. Boy kills people to feed plant. Plant eats boy. Boy and girl do not live happily ever after.

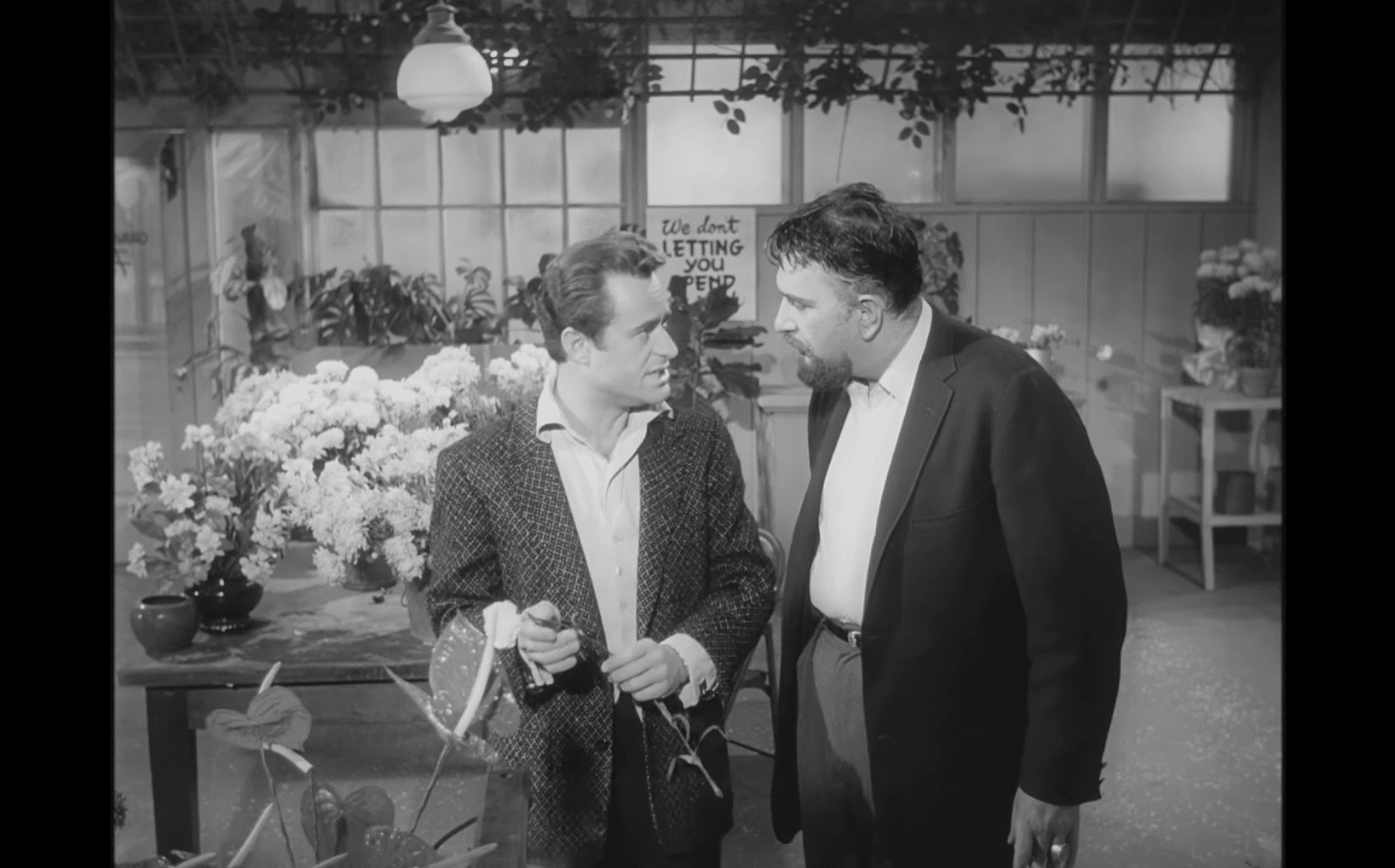

The boy is Seymour Krelboined (Jonathon Haze), and the girl is Audrey Fulquard (Jackie Joseph). Together, they work at Gravis Mushnik’s (Mel Welles) rundown florist shop on Skid Row.

While the picture wasn’t a runaway success, it developed a dedicated cult following, culminating in an off-Broadway musical adaptation in 1982. Four years later, the Frank Oz-directed film adaptation of the musical arrived in theatres. The 1986 film is delightful and has ultimately eclipsed Corman’s original in terms of popularity and public memory. However, one realizes just how significant the 1960 film is when we see how much of it survives in its adaptations.

If you’ve only ever seen the 1986 film, watching Corman’s original is something of a revelation because it’s all there: Mr. Mushnik’s entire characterization, the crazed dentist and his masochistic patient (played by Jack Nicholson), the signature cry of “feed me!” from Audrey II (or Audrey Jr as she’s called in the 1960 film). The stage and later film adaptations embellish and expand its elements (not least in the fabulous musical numbers), but the blueprint was all there in Corman’s original.

Indeed, Corman’s film deserves praise. It’s witty and sharp, constantly returning to earlier jokes to squeeze out every bit possible. For example, once Audrey Jr’s victims have attracted police attention, we’re introduced to two bizarre detectives: Joe Fink (Wally Campo) and Frank Stoolie (Jack Warford). Stoolie asks Fink how his kids are. “Lost one yesterday,” replies Fink. “How’d that happen?” asks Stoolie. “Playing with matches.” “Well, those are the breaks.” It’s a brilliant piece of back-and-forth silliness that feels like a forerunner to similar setups in 1980’s Airplane. Sadly, neither Fink nor Stoolie feature in the 1986 version.

Another element that wasn’t carried over is AIP-regular Dick Miller. He plays a man with a swagger and a penchant for eating flowers. He’s only in a few scenes but steals them nonetheless. Mushnik hands him a bouquet and Miller pulls out a saltshaker and pours it on, insisting that the best-tasting flowers come from the out-of-the-way places. This works on its own, but when we notice Miller in the background of the scene, still chewing on petals, the bit really comes together.

That sense of humor is present in most of Corman’s works, and it’s especially evident in interviews he gave over the years. In 1990, Corman appeared on an episode of Face to Face, in which he was interviewed about his life, work, and ethos. The presenter notes that Corman had (at the time) made over 200 films and then mentions the filmmaker was “reviled as a peddler of exploitative trash.“ An infectious grin breaks over Corman’s face. He was in on the joke and always had been.

He knew the ropes of mass entertainment and how to achieve it. At the same time, this isn’t to suggest that his work is artless. On the contrary, much of it is brilliant, from his striking Edgar Allan Poe adaptations with Vincent Price to his well-made science fiction offerings like 1957’s Not of this Earth – which, in turn, is complemented by its sillier (but no less entertaining) co-feature release partner: Corman’s Attack of the Crab Monsters.

Over the last year, The Little Shop of Horrors has received a new Blu-ray release courtesy of Film Masters, and a remake is planned in the near future – with which Corman himself was set to be involved, along with one of his students, Joe Dante. This author sincerely hopes that some of Corman’s earlier works currently sitting in licensing hell (1956’s It Conquered the World, for example) eventually receive similar opportunities.

Indeed, having Corman’s work available on home video (or back in cinemas and on television) is a good thing. The more chances there are for audiences to discover and rediscover his work, the better. Even if you were to plan a Roger Corman marathon, it would only scratch the surface. You could program a night of his Poe adaptations, an evening of his ’50s monster movies, a selection of his gangster pictures, or a run of his sleazy, gory ’80s horrors. Of course, you could also curate Corman’s comedies, with The Little Shop of Horrors taking pride and place at the top of the list.

For his entire career, Roger Corman listened to audiences as they cried out, “Feed me!” And every time, he dutifully obliged. In the process, he helped filmmakers who themselves have left indelible marks on the American film landscape. In the end, it’ll always come back to him.

Cheers, Roger.

Continue the Corman celebration with Tony Timpone’s previously unpublished Roger Corman interview as the “King of the Bs” recounts 13 of his favorite directorial endeavors.