It costs a lot of money to open a big musical on Broadway—anywhere from $18 million to $32 million just to get in the door.

“The Lion King” marquee, 2005. Photo by Diego Torres Silvestre.

So, if you wanna be a producer and you have a golden ticket at your disposal to get you through that door more easily, who could blame you? Welcome to a whole new world where the golden ticket is synergy, branding and intellectual property on Broadway. “Intellectual property” is not a new phrase—it was supposedly coined in the 19th Century during an early copyright dispute—and it simply means a creative work from which income can be derived. The big difference, some 200 years later, is that intellectual property—TV shows, music catalogues, comic strips, and most of all, movies—can be marketed and sold to the American public in ever more profitable ways.

As the shopworn adage goes, on Broadway you can can’t make a living but you can make a killing; indeed the animated Disney film, “The Lion King,” earned nearly one billion dollars in worldwide box office release; however, the stage version, also playing around the world (and still doing very well on Broadway), has grossed ten times that amount. Talk about hakuna matata—no worries.

Currently, the most robust traffic on the stage regarding intellectual property comes from Broadway’s eternally complex dance with Hollywood.

There’s nothing new about adapting movies as the source material for musicals; the first significant adaptation was “Carnival in Flanders,” a 1953 bomb, which still yielded the standard “Here’s That Rainy Day.” The trend really began in earnest during the mid 1950s, with such screenplay-driven musicals as “Fanny and Silk Stockings” (based, respectively, on a trilogy of French films and the Greta Garbo movie, “Ninotchka”). Critics who condemn the latest tsunami of movie-based musicals have short memories; as an example, from the 1966-67 season to the 1972-73 season, Broadway played host to numerous musicals derived from original screenplays, including (but not exclusively): “Sweet Charity,” “Illya Darling,” “Henry, Sweet Henry,” “Golden Rainbow,” “Promises, Promises,’ “La Strada,” “Ari,” “Georgy,” “Applause,” “70, Girls, 70” “Sugar,” “A Little Night Music.” Do you immediately recognize the films on which they are based? Probably not, because in the past, theatrical producers went out of their way to distance their new stage properties from the cinematic source by creating a new identity for the musical show or at least by changing the title. (I’ve provided the answers in a postscript.*) When producer David Merrick bought the rights to Billy Wilder’s film, “The Apartment,” and reimagined it as “Promises, Promises” in 1968, it wasn’t because he was hoping to cash in on the film’s “huge fan base.”

It’s hard to know exactly when Broadway realized it had more to gain than to lose by embracing its movie antecedents; there were a few outliers (“Destry Rides Again,” “Shenandoah”), but by the 1980s, when there was an explosion of original film musicals adapted directly to the stage (“42nd Street,” “Singin’ in the Rain,” ‘Meet Me in St. Louis,” etc.), it seemed futile to hold back the tide—why conceal what you were paying for?

The major difference in the 21st Century is that the film studios that own these potentially lucrative intellectual properties eagerly opened up their vaults and now actively produce or co-produce the stage musical version themselves. This trend was initiated by Disney Theatrical Productions, of course, setting up its own vast stage production division, staging and supervising multi-million dollar versions of “Tarzan,” “Mary Poppins” (originating on the West End, co-produced by Cameron Mackintosh), “The Little Mermaid,” “Newsies,” “Aladdin” and “Frozen” (itself a gloss on Broadway’s “Wicked”). Disney’s endeavors were largely successful, often with several shows running simultaneously; in fact, within its three-decade reign as a magic kingdom in Times Square, Disney shows have notched up a mind-boggling combined 25,000 performances—and counting.

“Legally Blonde” at the Palace Theater, 2008. Creative Commons Attribution.

Dreamworks followed in Disney’s big, yellow footsteps with “Shrek the Musical;” New Line Cinema helped underwrite its properties “Hairspray” and “The Wedding Singer,” MGM Onstage was behind “Legally Blonde,” “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang” and “Some Like It Hot” (the second Broadway version!); Columbia Live Stage, a division of Columbia Pictures, brought musical versions of their properties “Groundhog Day” and “Tootsie” to Broadway. Universal Pictures (as part of a number of different consortiums) was a pioneer in bringing “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” to Broadway, back in 1978, in exchange for the film rights and struck one of pop culture’s most prodigious gushers by shepherding “Wicked” to the stage (guess who’s distributing this year’s film version?). Sony Theatricals licensed one of their most enduring and valuable intellectual properties, your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man, to Broadway in 2011’s “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark.” Alas, it didn’t make many friends and closed as the biggest flop in Broadway history, losing $60 million of its investment; Sony did much better with its Michael Jackson catalogue in “MJ The Musical.”

Promoting intellectual property for Broadway in the 21st Century is not without its challenges.

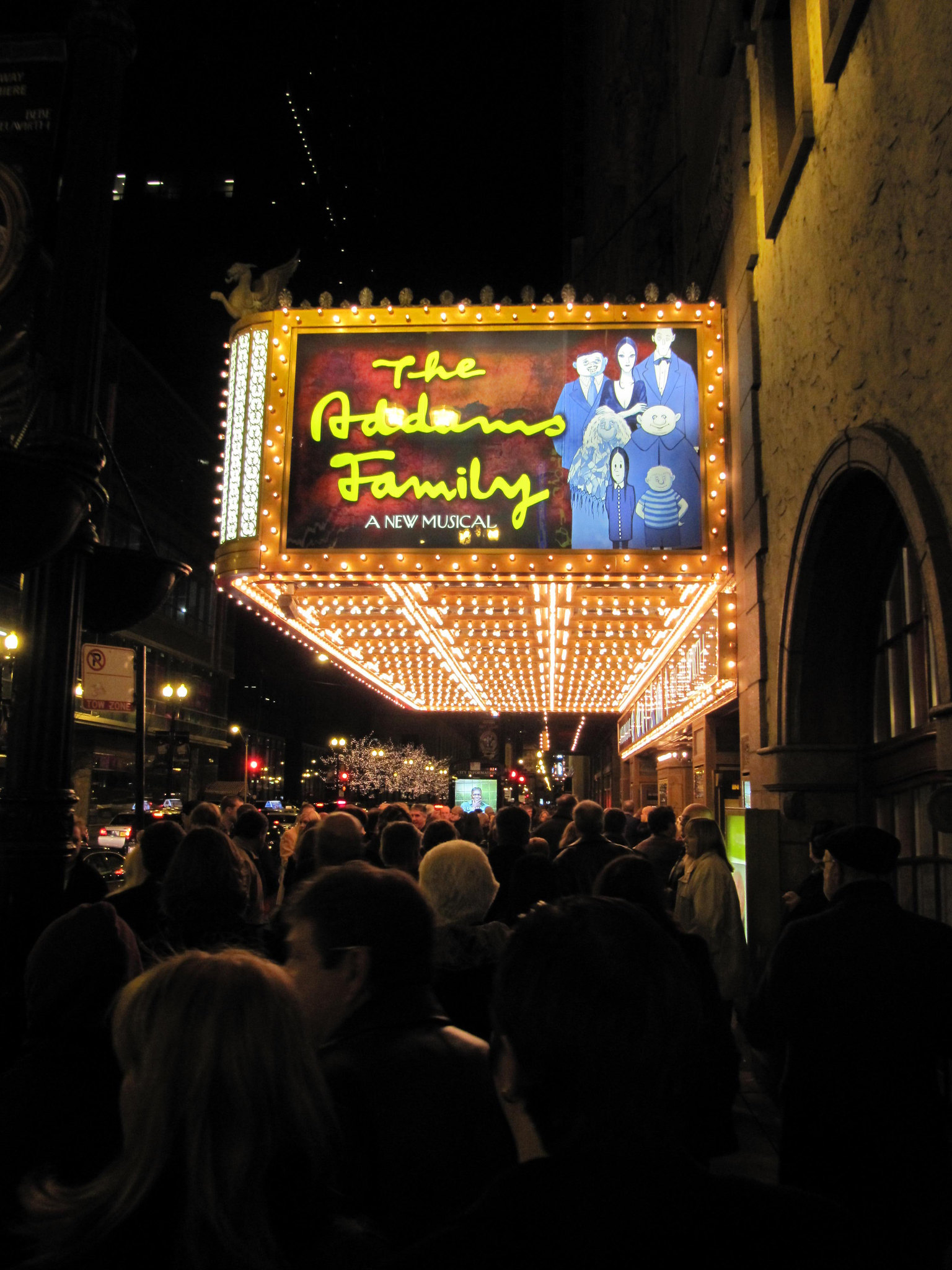

“The Addams Family” marquee on Broadway, 2009. Photo by Gary McCabe.

There has to be a balance between something recognizable for fans and something compelling on its own terms for new customers. The branding synergy between a previously popular movie brand and its new stage equivalent can become increasingly determinate, at times even suffocating. The poster art and costume design concept for 2007’s “Legally Blonde” was intensely similar to its screen antecedent; after all, there was no way that MGM On Stage was going to waste its branding dollars by re-titling their new musical as “Elle!” or “What, Like It’s Hard?” One has sympathy for the patrons who spent $125 each for their tickets and were surprised not to find Reese Witherspoon appearing on-stage.

The stage analogues of “Ghost,” “A Christmas Story,” “School of Rock,” “Pretty Woman” and “Beetlejuice” were also particularly beholden to their film predecessors, directly deploying previous logos, designs and visual effects. In fact, “Young Frankenstein,” “Ghost,” “School of Rock,” “Doctor Zhivago” and “Beetlejuice” interpolated signature songs from the movie versions into their new scores, banking on the assumption that audiences would have been disappointed not to hear, say, the movie theme “Somewhere My Love” in a theater piece based on “Doctor Zhivago.” The creators of “The Addams Family” stage musical were determined never to use the television show’s immortal theme song in its score. Apparently, audiences during its pre-Broadway tour in Chicago were, to say the least, dismayed not to hear that beloved tune. A licensing contract was quickly drawn up and: Da-da-da-dum—Snap! Snap!

Still, although there seems to be a never-ending stream of film adaptations, not all of them are slavish or unimaginative.

The most successful of these versions tended to involve less well-known cinematic IP which gave the theatrical creative teams more room to expand their wings into more unpredictable directions. “Billy Elliot” was a British film from 2000 that garnered modest commercial and critical success, but the musical version of this Cinderella tale won the 2008 Tony Award for Best Musical, as well as nine other Tonys. Another non-commercial project, an Israeli movie from 2007 called “The Band’s Visit,” was given the Broadway treatment and was such a departure from the usual Broadway sound-and-fury that it captivated audiences and won ten Tonys (including Best Musical).

Perhaps it’s the smaller films, with less excess baggage of branding and preconceived notions that prove more adaptable to the critical expectations of the day; “The Bridges of Madison County,” “Waitress,” and this season’s “Days of Wine and Roses” (as well as “The Outsiders,” which also had its own famous fictional source to live up to) were more intimate musical narratives that engaged their cinematic inspirations in a less bombastic way, took what they needed from their intellectual properties, and offered audiences their own, new theatrical vocabulary.

Now, let’s assume that you’re a clever—if not crafty—Broadway producer (assume away!!). You might hit the trifecta by adapting a popular film or TV show into a hit Broadway stage musical and then adapt that stage show into a full-blown cinematic property; three bites at the IP apple, as it were. You’d also be lining up behind “Sweet Charity,” “Nine,” and the recent film of “Mean Girls” among others. That kind of luck only happens to a few Bialystocks and Blooms out there—and, of course, it even happened to the producers of “The Producers.”

*(In order: “Nights of Cabiria,” “Never on Sunday,” “The World of Henry Orient,” “A Hole in the Head,” “The Apartment,” “La Strada,” “Exodus,” “Georgy Girl,” “All About Eve,” “Make Mine Mink,” “Some Like It Hot,” “Smiles of a Summer Night”).

Laurence Maslon collaborated on the PBS six-part series “Broadway: The American Musical” and is the host of the weekly radio program, “Broadway to Main Street,” on WLIW-FM.

American Masters, produced by The WNET Group, brings Broadway and Beyond to the New York/CT/NJ area this May and June. If you live in the tri-state area, visit thirteen.org/broadway for more information.