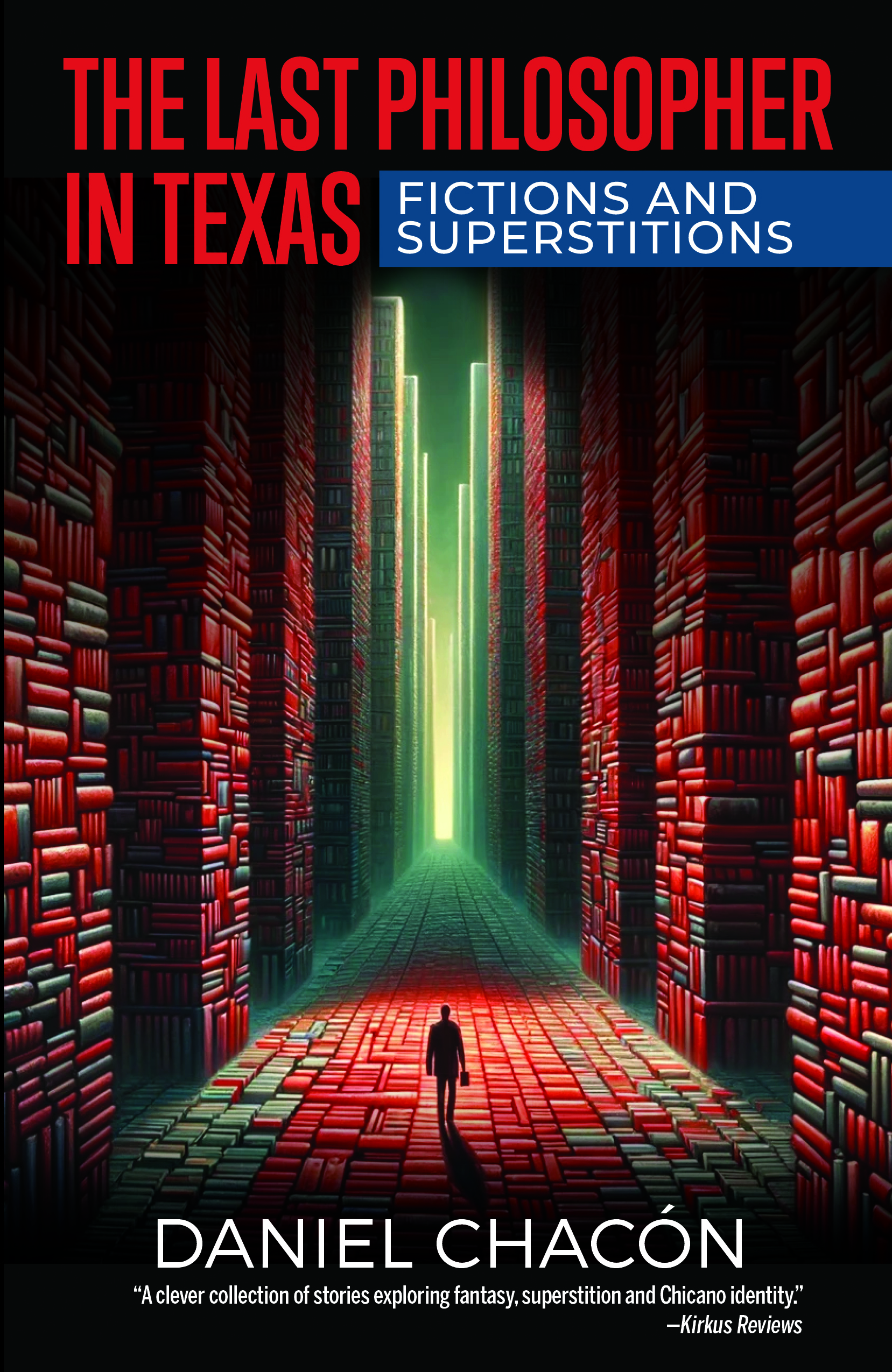

Introduction by Lise Olsen

El Paso author Daniel Chacón likes to weave stories and dream up characters in the middle of ordinary episodes of life. The titular character of his new short story collection, The Last Philosopher in Texas: Fictions and Superstitions, came to him as he was walking his dog in Pecos, the windblown West Texas town where his father once lived. “It was really weird because there’s a lot of meth heads and there’s a lot of boarded-up windows,” he told the Texas Observer. He remembers spotting an ad for a manager at a fast food restaurant, one of the town’s best-paying jobs. The story took off when he thought: What would have happened If I had come up here after graduation?

Chacón is originally from Fresno and got a master’s degree in creative writing in Eugene, Oregon, but for decades El Paso and the border has been his home. A longtime professor, Chacón currently serves as chairman of the University of Texas at El Paso’s creative writing program, which bills itself as the nation’s only fully bilingual program, and he hosts a Sunday public radio program on KTEP called “Words on a Wire.”

“Okay, so the Chicano Time Traveler says to that pendejo Columbus, ‘Go home, whitey! We don’t need your ass over here.'”

In his life and work, Chacón, who is something of a philosopher himself, deeply probes limits and connections between the possible and the impossible, the imagination, the dreamworld, and what we call “reality.” For him, the U.S.-Mexico border is a place where those boundaries tend to disappear. Lately, he finds himself feeling like a time traveler in the undergraduate classes he teaches. Every year, he ages, and the cultural and literary references he uses become more unfamiliar to students, whose faces change but who remain forever young. “It’s not just in terms of age. I feel like I came from another time and place,” he said.

Back in 1985, Chacón founded the Chicano Writers and Artists Association along with Fresno State classmate and friend Andrés Montoya. “I was a little younger when I joined the movement,” he recalled. “As progressive as they thought of themselves, it was all very male-centered and patriarchal and especially anti-gay,” he recalls. In one story in his new book, “The Chicano Time Traveler,” he explores how Chicano culture has evolved by recounting an exchange with an uncle whose ideas clash, sometimes hilariously, with inclusive Chicanx culture. Below is that story, from his 2024 book, reprinted in full with permission of the publisher Arte Publico Press.

“The Chicano Time Traveler”

Tío Rudy told me he had a story idea, and that he would sell it to me for a hundred bucks.

He said I would make lots of money, because it might be the most important story ever told. They might even make a Netflix series out of it, then I’d be rich.

“En serio. You could be successful.”

“I’m okay,” I said.

“Shit! Then how come you ain’t got no ruca?”

“Maybe having a girlfriend’s not my priority,” I said.

“Shi-it!” he said in two long syllables. “Everyone wants a ruca. Unless you’re…”

He looked me up and down.

“Anyway, bro. I’d write it myself, pero, ¿sabes qué? I don’t write too good.”

We were in the backyard of my abuela’s house on Mother’s Day, drinking beer, the sun falling down.

“Pero, my idea, it’s chingón!”

Rudy was an old-school Chicano, a living remnant and stereotype from the barrio. He even dressed old school cholo, and he had tattoos from his gang days, like a little dog paw above his left eye. He was a Fresno Bulldog, East Side. I say he was, because now, pulling the oxygen tank along with him everywhere he went, he didn’t participate in la ganga, but he did say, “Once a gang member, always a gang member.” He was proud to call himself a veterano.

“You’re a writer,” he said. “You could do this, homes.”

He actually used the word “homes,” as if traveling from the past. I hadn’t heard that word in at least two decades, not since the word was replaced by “homie” and “homeboy.”

Rudy was approaching sixty, and he looked it, not like a “forty is the new sixty look,” but like an old man.

His hair was balding, with some stubs standing up like under the power of static electricity, and his cheeks sagged down like a walrus.

“Okay, so check it out. Here’s the idea. It’s called ‘The Chicano Time Traveler,’ ese.”

I wondered, did anyone say “ese” anymore?

“Okay, so the Chicano Time Traveler… Man, this vato is a superhero. He goes through time, man, in and out of any time he wants, and he changes all the fucked-up things the gabacho has done to us, ¿entiendes? ¿Sabes qué? This fucker is mero mero! Like for example, say Christopher Columbus is coming to America, our hero travels in time and is right there on the beach waiting for that maricón.”

Ow, that hurts, I think. I ask him, “Why do you call Columbus a maricón?”

“I don’t mean a gay dude, m’ijo. I just mean, he’s a fuck head, ¿entiendes?”

“But why maricón?” I ask.

“All right, bro. Let’s say, instead of maricón, pendejo. That better?”

“Less offensive,” I say.

“Okay, so the Chicano Time Traveler says to that pendejo Columbus, ‘Go home, whitey! We don’t need your ass over here.’

“And Columbus would say, ‘Nah, man! I’m here to get me some gold and shit.’

“Pero ¿sabes qué? The Chicano Time Traveler knows how to throw down chingazos, so he fucks up Columbus real good.

“And that gringo turns around and never comes back. And, ¿sabes qué? When the Chicano Time Traveler goes back home to Fresno or East Los or Chuco, or from wherever he lives in Aztlán, things would be different. Brown people would be in charge, man. Chicanos would be mayors and shit. Fucking lawyers and doctors and shit… And people struggling like me wouldn’t have one job. We’d have two jobs! Making la feria, ¿entiendes? All the native peoples would be hooked up, because we’re native, bro. Don’t forget that. I know you’re a little light-skinned, güerito, but it’s true. We’re fucking natives!”

“Okay, let me ask you just one thing,” I said.

“Want another beer?” he asked.

“Yeah!”

So, he grabbed two cans from the cooler and tossed me one. I caught it.

“So, what do you think of my story, bro! Pretty fucking brilliant, no?”

“Well… I have some questions. First of all: Why is he ‘Chicano’?”

“What the fuck you talkin’ about?”

“That’s an antiquated term,” I said. “Rooted in misogyny. Maybe he should be the ‘Chicanx’ or the ‘Latinx’ Time Traveler. That’s what the young activists are saying these days.”

“Fuck that. That’s sellout shit. I’m a Chicano.” And he started to sing that old Texas Tornados song:

Chicano! Soy Chicano!

And I’m brown and I’m proud

And I’ll make it in my own way.

“Our young people today…” I said, interrupting his song, “…they want to leave out gender, too. It’s no longer fundamental to identity. In fact, why don’t you call it The Chicana Time Traveler?”

“He ain’t no girl,” he said.

“Might be better if she were,” I said. “But even if he is a he, why can’t we say ‘Chicana’? Why can’t that term mean an entire community of men and women and nongendered people? For generations we’ve used the term ‘Chicano’ to mean everybody in the barrio, although it’s clearly a masculine noun. Why can’t we use the feminine term—CHICANA—to indicate everybody? Why stick to patriarchal rules of language?”

“Fuck you!” he said and he walked away, dragging his oxygen tank with him. “Sellout piece of mierda!” he said. “I’ll take my story somewhere else, vendido.”

As I was trying to sleep that night, I had a dream about Rudy.

At least, I think it was a dream. It seemed real, somewhere between memory and a dream. We were in my abuela’s garage drinking beer, listening to some tunes, and everything seemed like virtual reality, like I knew it was all false, but the detail was amazing. I saw the United Farm Workers’ poster, and I could even see the glare of the garage lights on the smooth surface. Underneath the poster, I saw a worktable with some tools scattered about, a crescent wrench, a hammer, screwdrivers and some nails and screws. There was even an old 7-11 Big Gulp cup that must have been sitting there for a long time.

It was the 1990s. I was maybe sixteen years old. I wanted to be a writer back then, so of course I wrote poems and stories. This night in the garage, I read Rudy what I was certain was my best story. I don’t even remember what it was about. After it was over, he slowly shook his head.

“Dude, that was off the fucking wall! You’re going to be a famous writer. I know it in my gut, ese. You got talent!”

Rudy was a hard-core gangster in those days. He did all kinds of crazy shit, but whenever I was with him, he would try to be a good uncle. He would give me beer and smoke weed with me, but he felt an obligation to teach me something. In this memory or dream, Rudy suddenly got serious.

“¿Sabes qué?” he said. “No matter how famous you get, never forget you’re a brown man. They’re going to try to take you down, ese, but you got to fight,” he said. “Don’t forget your people. You got to fight the power.” And I believed him.

I took that with me when I got my bachelor’s degree in English. But since it quickly became clear that I was not likely to make a living as a writer, I went to law school and became a lawyer, an activist. For the last ten years I’d been working at a private law firm, and they were about to make me a partner, the first Latinx person in the firm to have such status. I was making good money, and every time we were allowed to do pro bono work, I always remembered Tío Rudy and tried to help out la gente.

In this dream, we were in my abuela’s garage drinking beer. We were listening to Led Zeppelin. And I said, “You know what, Uncle Rudy? I like your story idea. I think it’s really good, and I’d like to write it.”

“What story, fool?” he asked.

“The Chicano Time Traveler,” I said.

“I have no idea what you’re talking about,” he said.

And I explained the idea he would tell me twenty years or so in the future. He laughed when I told him about Columbus getting his ass kicked by our cholo hero.

“That’s a great story, homes! ¿Sabes qué? I’m gonna remember that shit! You watch! I’m gonna remember that shit. ¡Por vida!”