Landing in Florida in late September 2022 to report on damages from Hurricane Ian, NBC News correspondent Jesse Kirsch, who describes himself as “extremely culturally Jewish,” realized that evacuation orders had been issued on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year. The state has the nation’s third-largest Jewish population, and Kirsch wondered how Floridians would be preparing for the holiest day of the Jewish year, Yom Kippur, which comes nine days after Rosh Hashanah.

Kirsch’s informed hunch paid off when he learned of a couple that had safely stored a synagogue’s two Torah scrolls in a vault on Sanibel Island. The holy scrolls, including one that had survived the Holocaust in Europe, remained completely dry.

As the couple held the scrolls during their interview, Kirsch instinctively kissed his fingertips and touched each scroll, as he would do in a synagogue to show his respect for the Jewish faith. “Nightly News” producers included that candid moment of devotion in the final video, and viewers reached out to share their appreciation.

“To see how it resonated with people validated all the more doing the story,” Kirsch said. “I was very proud to have been able to tell it.”

Much like the nearly 4,000 years of broader Jewish history, the Jewish American story is one of surviving and thriving. The United States, which has guaranteed freedom of religion since 1791, has remained a haven for Jewish immigrants since the earliest days of European colonization. Crypto-Jewish settlers fled persecution in 16th-century Spain and Portugal, Joachim Gans arrived with the English Roanoke Colony in 1585 and the first Jewish community came to New York in 1654. Jewish soldiers took part in the American Revolution and every U.S. war thereafter.

From 1880 to 1924, Jewish immigration peaked with the arrival of around 2.5 million Eastern European Jews, including seven of my ancestors. Many entered through New York past the Statue of Liberty, which the Jewish American poet Emma Lazarus nicknamed the “Mother of Exiles” in 1883. Since 2006, May has been the federally designated month to celebrate our country’s centuries of Jewish American heritage.

However, there’s no clear definition of “Jewish American,” since people can identify as Jewish through religious, cultural and/or ethnic ties. Judaism, with numerous denominations across the globe, has followers representing every race. Major ethnic Jewish subpopulations include Ashkenazi (from Eastern Europe), Sephardic (from Iberia/Mediterranean), Mizrahi (from Middle East/North Africa) and the Beta Israel (from Ethiopia). Some who may not practice Judaism may still consider themselves “culturally Jewish,” and people with partial Jewish ancestry may self-identify as Jewish.

With this in mind, estimates of the U.S. Jewish population range from up to 6.3 million to 7.5 million or more, covering a diverse group with a wide range of religious, political and social views. Many Jewish Americans like Lauren Peikoff, Executive Producer, Live Events and Peacock for MSNBC, center their Jewish identity on traditions passed down through their families, like Shabbat dinners and Passover Seders.

“I’m a nondenominational Jew who believes deeply and heavily in tradition and in the past that guides the future,” Peikoff said. “I’m singing the same songs that people in my community have sung for thousands of years, eating the same foods and partaking in the same traditions.”

A lot of Jewish American culture, especially of Ashkenazi origin, has seamlessly entered mainstream culture. People regularly eat bagels, pastrami and kosher pickles or drop Yiddish-origin words like “chutzpah,” “klutz” and “schmooze,” often without thinking of their Jewish origins. Jewish American innovators created innumerable ubiquitous products including Google, blue jeans, lasers, WiFi and GPS and even the polio vaccine.

Notables like EGOT-winning entertainers Barbra Streisand and Mel Brooks, Pulitzer Prize winners Art Spiegelman and Tony Kushner and baseball icon Sandy Koufax drew on their Jewish identities to create major cultural moments. Other times the Jewish identities of celebrities and newsmakers can come as a surprise, as amusingly discussed in Adam Sandler’s “Chanukah Song” on “SNL.”

Prominent Jewish Americans include the Biden administration’s Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Nobel Prize laureates Bob Dylan and Ben Bernanke, multibillionaires Mark Zuckerberg and Larry Ellison and legendary athletes Sue Bird and Mark Spitz. Our own parent company, Comcast, was co-founded by two Jewish Americans, Julian Brodsky and Daniel Aaron (who was a refugee from Nazi Germany), as were subsidiaries NBC, by David Sarnoff, and Universal Pictures, by Carl Laemmle.

Yet this rich tradition of Jewish American accomplishment is paired with the never-ending threat of antisemitism. The Nazis’ systematic murder of 6 million European Jews during the Holocaust, known in Hebrew as the “Shoah” (catastrophe), casts long shadows not only over the approximately 40,000 Holocaust survivors living in the U.S. and their families, but also the U.S. Jewish community as a whole.

Since the start of the Israel-Hamas war on Oct. 7, antisemitism in the U.S. has reached levels unseen in recent history and Jewish Americans find themselves in the center of intense debates over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and U.S. foreign policy in Israel and the Middle East.

Many Jewish people felt verbally attacked by anti-war protests on college campuses, like the recent demonstrations at Columbia University.

Chaya Droznik, a Columbia junior, said a protester told her that “Oct. 7 is about to be every day for you guys.”

Other Jewish people who oppose the war and protested said they felt attacked by pro-Israeli rhetoric and when law enforcement stormed campus.

“I feel unsafe when [a professor said] I’ll be ‘on the last train to Auschwitz,’” said Soph Askanase, a Barnard College student and Columbia demonstrator. “When you are arrested, dragged out with zip ties and have red marks on your wrists for days after the fact… that is what being unsafe is.”

For CNBC anchor Sara Eisen and many descendants of Holocaust survivors, the deadliest attack against Jews since World War II made the previously unimaginable seem possible. Eisen remembers how her grandfather, who survived Auschwitz, would come to her classroom, roll up his sleeve to show the number tattooed on his arm, and tell her classmates about his experiences and his parents and brother who did not survive.

“After all of the unimaginable brutalities that he faced, he somehow was able to be an optimistic person and an amazing storyteller. I think it inspired me to go into journalism and become a storyteller myself,” Eisen said. “I feel a responsibility to tell that story and keep educating people about that history so that we don’t repeat ourselves.”

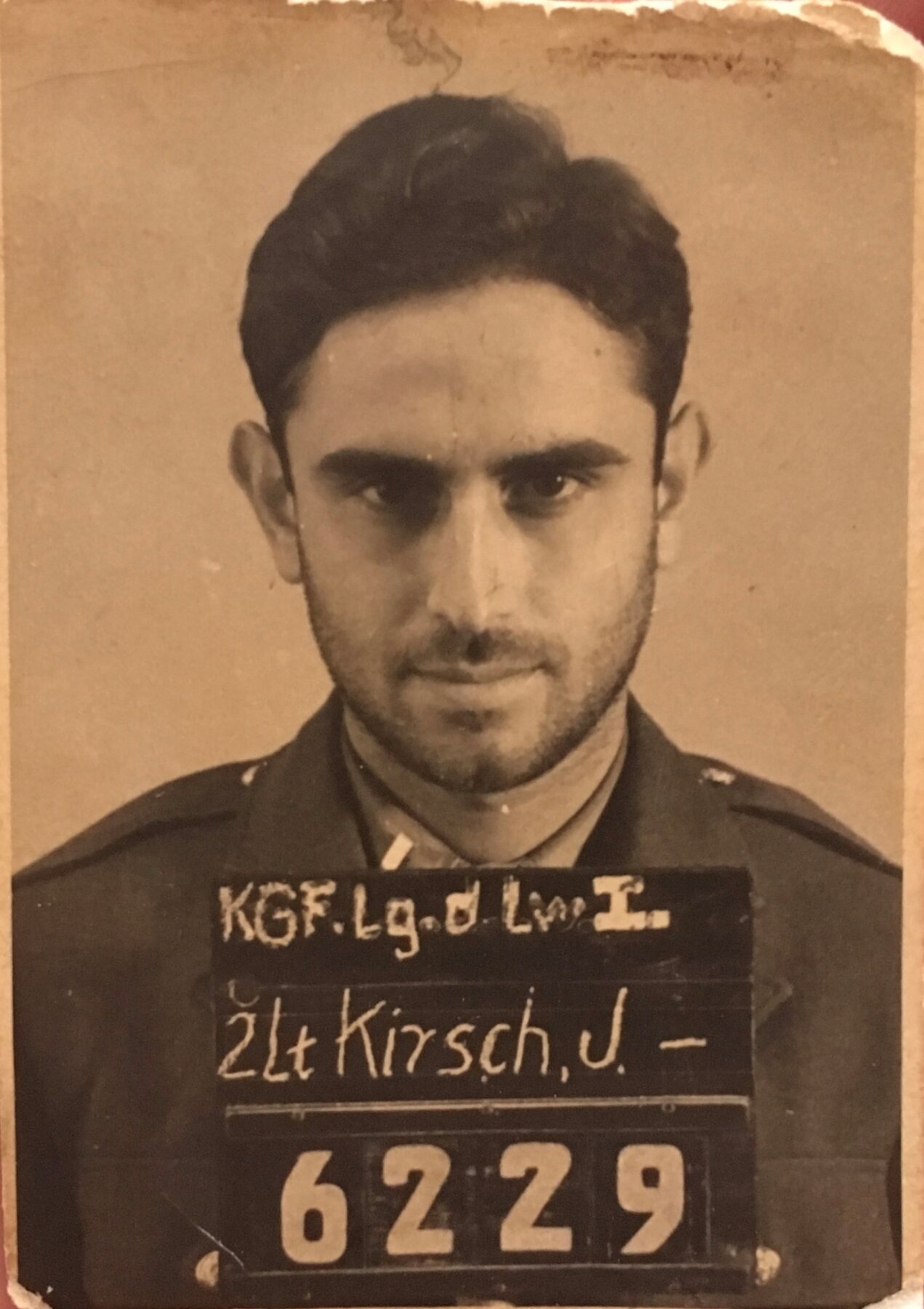

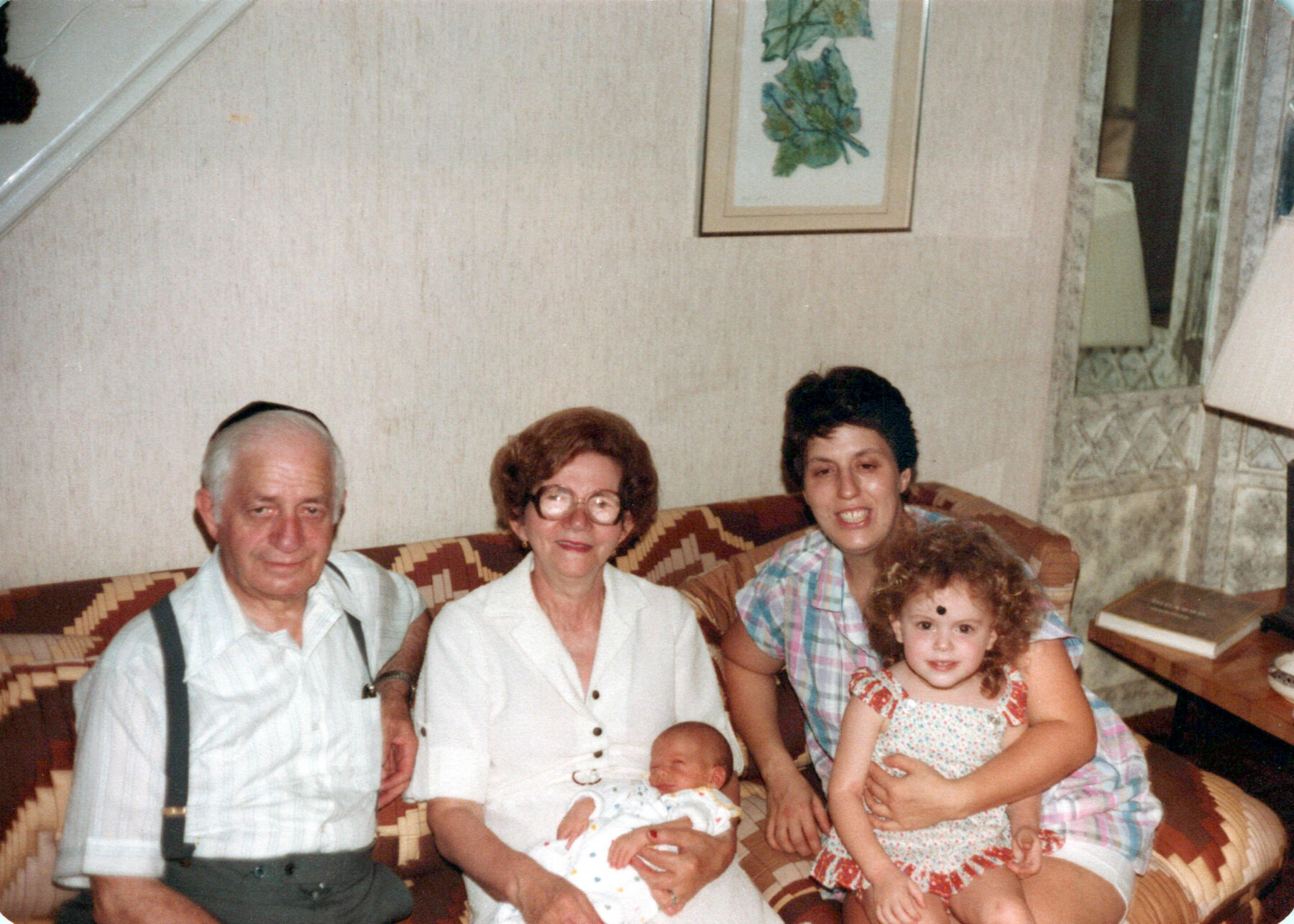

Abigail Symonds, a digital distribution manager for NBCUniversal in Los Angeles, draws inspiration from her survivor grandparents, Chana and Moshe, who stayed religious even after most of their families were killed and they resettled in the United States. Often the only Orthodox Jewish woman in her workplace, Symonds keeps kosher, wears long skirts to work and uses more time off for religious holidays than most of her Jewish co-workers.

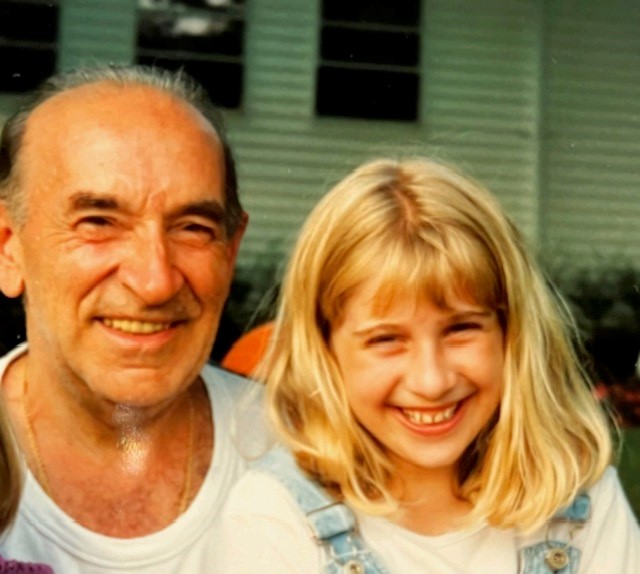

Symonds is named after her late aunt, her grandparents’ oldest child who died in the Holocaust, and she thinks that helped forge a strong bond with her grandparents. She remembers how her grandfather, who never brought up his wartime experiences, got “extra excited” to see her.

“The hug that I got from him, that felt really good,” Symonds said. “I felt really special.”