Last Updated on May 16, 2024 by Angel Melanson

For over 60 years, Roger Corman served as a one-man film factory, producing and distributing more than 400 features and directing over 50 genre flicks during his breathless career. Not bad for someone who started in a studio mailroom!

This past Thursday, Hollywood’s most prolific independent filmmaker passed away at age 98. Heartfelt reaction have poured in, from the dozens of major filmmakers whose careers Corman launched to the countless fans who caught his films in drive-ins, second-run theaters, late night TV or streaming. I met the charming Corman many times during my FANGORIA tenure, and in 2015 I interviewed the King of the Bs to discuss both the Top 13 favorite films he directed for American International Pictures and others, as well as the movies he produced and/or distributed through his own companies (coming in Part Two). In honor of the much-loved man, let us celebrate the Cinema of Corman, as told in his own words. (Titles arranged according to year of release.)

Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957)

A group of scientists (including Gilligan’s Island’s Professor, Russell Johnson) get stranded on a sinking island with giant, mutated crustaceans in Corman’s gory creature feature.

“The crab monster was 13 or 14 feet wide, and we had it on the rocks at Carrillo Beach,” the Detroit-born Corman recalled, “and the waves were coming up and hitting it. I had to shoot fast, and my great sense as a director was, ‘Fellas, do it again. I can see your feet underneath the crab monster. Hold the damn thing closer to the rocks!’”

Not of This Earth (1957)

The second half of the Attack of the Crab Monsters double-bill starred deep-voiced Paul Birch as an alien who collects human blood for his dying planet. The movie provided Dick Miller, a favorite Corman stock company player, with a memorable bit role.

“There was a part for a door-to-door salesman who comes to the house where Paul Birch is living,” noted Corman. “The salesman wants to come in and demonstrate a vacuum cleaner, and of course, Paul is delighted to have him come in because he’s going to kill him and drink his blood. There was a radio pitchman who had exactly the quality I wanted for the salesman, and I was going to hire him. I was talking to Dick Miller, and Dick said, ‘What do you want, a pitch man or an actor?’ And I thought about it and said, ‘You’re right, Dick, you play the role. You’re the actor.’”

A Bucket of Blood (1959)

Corman hired the marvelous Miller again for one of his few starring roles, A Bucket of Blood, a clever horror comedy churned out in five days! “I had done one of [my horror] pictures, and at the sneak preview, there was a key scene which was to be a major shock,” Corman explained. “But when you’re shooting that sort of thing, the shock itself is not that crucial, it’s the building of suspense and impending horror that leads you to the shock. So, the scene was working perfectly. I could sense the audience getting into the horror mood, and the moment of the shock, it worked exactly the way I wanted it to. The audience screamed, and then there was a little laughter right after the scream. And I said, ‘What did I do wrong?’ I realized, ‘I didn’t do anything wrong. The shock worked perfectly.’ It was laughter of appreciation or knowledge that they’d been sort of had, that I’d manipulated them. And from that I came up with the idea that horror and comedy are connected. Since I wasn’t certain of that theory, I decided to shoot A Bucket of Blood to test the theory.”

The Wasp Woman (1959)

A youth-obsessed cosmetic executive (Susan Cabot) tests out a facial injection made from insect enzymes on herself. The nasty side effect: The concoction transforms her into the titular fiend.

“This happens very often, particularly on low-budget pictures when you don’t have full preparation or money or preparation time and money,” Corman remembered. “But the actual mask that Susan wore didn’t fit exactly. The mask wasn’t really right, and we rebuilt that mask during the lunch hour. It was supposed to work in the morning, and we rebuilt the mask and shot in the afternoon.”

House of Usher (1960)

Corman achieved his first critical accolades after he convinced distributor American International Pictures to take a chance on more highbrow fright fare, double the production budget and shooting schedule and to film in color. House of Usher’s success led to a series of Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, most starring the inimitable Vincent Price.

“I determined that Edgar Allan Poe was working from the unconscious mind, and I wanted everything to be artificial,” explained Corman, who studied English literature at Oxford. “I didn’t want anything to be realistic, because I felt the unconscious did not have a direct connection to the real world. So, I needed a sequence where Mark Damon’s character rode through a forest up to the House of Usher, and I didn’t know how to do it in an artificial way. Fortunately for me, unfortunately for the residents, there was a forest fire in the Hollywood Hills and everything was burned out, and there was nothing but twisted black portions of trees and so forth. We weren’t ready to shoot, but I quickly got the cameraman, a grip, a horse and Mark and shot him approaching the house through the burned-out forest.” (In a sad coincidence, Usher co-star Damon died on Sunday at age 91.)

The Little Shop of Horrors (1960)

This legendary horror spoof, shot in two and a half days (!), not only featured Jack Nicholson in a small part, but inspired a hit stage show and subsequent big-budget movie musical remake. At the time of his death, Corman and his friend and director Joe Dante were planning a sequel/reboot called Little Shop of Halloween Horrors.

“Little Shop was done almost as a joke just to see if we could do it,” the director laughed. “One of the reasons it was so successful is the fact the atmosphere of the cast and crew while shooting does affect the picture, and nobody took the picture seriously. So, we were all just fooling around having fun, and that affected the picture. We started shooting at 8:00 a.m., and at 8:30 a.m. the assistant director announced that we were hopelessly behind schedule!”

Pit and the Pendulum (1961)

Starring as the hero of Corman’s second Poe/Price picture, actor John Kerr expressed a little apprehension about playing a scene underneath the massive torture device of the title.

“We had this huge pendulum hanging and this blade, which wasn’t really sharp, but was sharp enough swinging back and forth and coming down lower and lower until it cut the character’s shirt,” Corman said. “Then we applied some blood as if it just cut his body. John was a little bit worried about that, and I said, ‘Don’t worry about it, John, I’ll get under the pendulum’ to show him he was totally safe. So, I got under there, and I saw this thing swinging, coming down at me, and I thought, this is not a good idea!”

The Premature Burial (1962)

Corman tried to step outside of the AIP umbrella for the next installment in his Poe cycle. “There had been a dispute between American International Pictures and me,” he revealed. “I had a percentage of profits of each picture. Pathe, the lab we were working with, wanted to start a distribution company. They knew I was thinking of doing Premature Burial, so they came to me and said, ‘Why don’t you make that picture for us?’ and I said yes. Vincent was under exclusive contract to American International, so I picked Ray Milland. On the first morning of shooting, Jim Nicholson and Sam Arkoff, the heads of American International, came to visit me on the set and congratulated me on making my next picture for them. The night before shooting, they bought the rights from Pathe Lab, and I was working for AIP again!”

The Raven (1963)

Fearing that the Poe pictures were starting to look alike and they were repeating themselves too much, Corman and series screenwriter Richard Matheson decided to bring humor into their fear formula. Lead Boris Karloff, however, took objection to co-star Peter Lorre’s improvisational shenanigans.

“After the first day of shooting, I was having coffee in the morning,” Corman recalled. “And while they were setting up the lights, Boris came to me and said, ‘Roger, I am a professional actor, I learn my lines, I am prepared to give a performance. Peter is out there making up his lines as he goes along, and I never know when to come in, I never know what he’s going to say.’

“So, I brought everybody together and explained that Boris had been trained in England in a classical style of acting. Peter was from Bertolt Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble, where they did a lot of improvisation, and he liked to work that way. What he was doing was very funny, but he was throwing Boris off. From Vincent’s standpoint, he could work both ways, and he was amiable through the whole thing. So, I said, ‘Peter, what you’re doing is great, but it does throw off some of the actors. Stay a little bit closer to the script.’ I said to Boris, ‘Boris, understand Peter works this way, so just adjust a little bit with him.’ Actually, it all turned out very well. Peter did stay a little closer to the script, and Boris loosened up.”

The Haunted Palace (1963)

In the midst of their Poe phase, Corman and his team (including Price) tackled another literary horror master for a change of pace.

“I felt, again, that I was repeating myself with the Poe films, and I suggested we go to [H.P.] Lovecraft and his The Case of Charles Dexter Ward,” Corman explained. “Jim Nicholson was always very good at titles, and after I shot the movie, he decided he wanted to call it a Poe film. So, we found a Poe poem titled ‘The Haunted Palace,’ and after the picture was over in looping, which is when you add dialogue or replace dialogue, I put in a few lines to refer to the poem. It was sold as a Poe film but was never planned as a Poe film. These things happen in marketing films.”

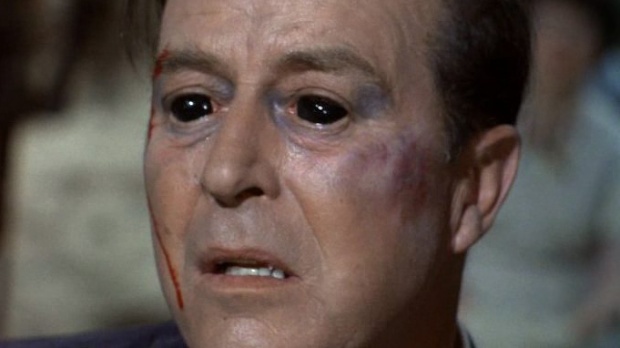

X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963)

The busy director (he helmed five films in ’63!) reteamed with Premature Burial star Milland for this well-received tale of science run amok.

“I started simply with the idea of a man who could see through things,” the former industrial engineer noted, “and my first thought, it would be some sort of scientist doing experiments, but that’s too obvious. I wanted to come up with something else a little bit more original. I generally write a four- or five-page outline of what I want the story to be before turning it over to the writer. So, I got the idea that it be a jazz musician, who as many jazz musicians do, took drugs. And he took some bad drugs, and he was able to see through things. I was about halfway through writing the treatment and thought this isn’t a good story at all. I threw it away and went back to the idea of a scientist experimenting.”

The Masque of the Red Death (1964)

Corman ventured overseas to make his penultimate Poe, arguably the finest film of his career.

“Masque had a very good script by Chuck Beaumont and Bob Campbell, maybe the best script of any of the Poe films,” said Corman. “We were shooting in an English studio, and they had just done a major period picture, Becket. What studios do is they have what they call a scene dock, and when a picture is finished, they break down a set, but they put the flats in storage. The flats are just what they are—flat sections of the set so they can be reused at some subsequent time. [Production designer] Danny Haller and I went to the scene dock, and there was nothing left of the original set, but we could see how beautiful the flats were. Danny did a really masterful job of designing an entirely new series of sets, but utilizing those flats. I had the best look and the biggest look of all of the Poe films.”

The Tomb of Ligeia (1964)

For his last Poe/Price venture, Corman hired Robert Towne, today regarded as one of the industry’s finest screenwriters. “Poe was working from the unconscious mind, and the unconscious mind isn’t really aware of the outside world,” the director said. “It gets its input from the eyes, the ears, the nose, mouth and so forth, and so therefore I should never show the real world; everything should be artificial, which I adopted on every Poe film. Finally, I got bored with my own theory. Bob Towne, who went on to Chinatown and Shampoo, was a friend of mine who wrote Tomb of Ligeia. I said, ‘Bob, I’m throwing out my theories about the artificial world entirely on this. I’m going to shoot in England, we’re going to go out in broad daylight on the beautiful English countryside and break every rule that I followed on each previous film.’”

TO BE CONTINUED…