Abstract

A vast literature shows parental education significantly affects children’s chance of attaining higher education even in high participation systems (HPS). Comparative studies further argue that the strength of this intergenerational transmission of education varies across countries. However, the mechanisms behind this cross-national heterogeneity remain elusive. Extending recent arguments on the “EE-SD model” and using the OECD data for over 32,000 individuals in 26 countries, this study examines how the degree of educational inequality varies depending on the levels of educational expansion and skills diffusion. Country-specific analyses initially confirm the substantial link between parental and children’s educational attainment in all HPS. Nevertheless, multilevel regressions reveal that this unequal structure becomes weak in highly skilled societies net of quantity of higher education opportunities. Although further examination is necessary to establish causality, these results suggest that the accumulation of high skills in a society plays a role in mitigating intergenerational transmission of education. Potential mechanisms include (1) skills-based rewards allocation is fostered and (2) the comparative advantage of having educated parents in the human capital formation process diminishes due to the diffusion of high skills among the population across social strata. These findings also indicate that contradictory evidence on the persistence of educational inequality in relation to educational expansion may partially reflect the extent to which each study incorporates the skills dimension. Examining the roles of societal-level skills diffusion alongside higher education proliferation is essential to better understand social inequality and stratification mechanisms in HPS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Access to higher education has markedly increased over the past decades, leading to the establishment of high participation systems (HPS) worldwide (Cantwell et al., 2018). Despite such an expansion of higher education opportunities, evidence shows that one’s educational attainment is unequally distributed based on socio-economic status (SES) (Marginson, 2016a, 2016b; Pfeffer, 2008; Voss et al., 2022). This persistent association between SES and education is often explained through the lens of stratification theories, such as maximally maintained inequality (Raftery & Hout, 1993) and effectively maintained inequality (Lucas, 2001). Comparative studies also highlight the influence of societal conditions, suggesting that highly tracked education systems are likely to exacerbate educational inequalities despite facilitating smoother transitions from education to work (Bol et al., 2019; Burger, 2016; Österman, 2018; Reichelt et al., 2019; Traini, 2022).

Although researchers have extensively investigated the unequal structure of educational attainment from longitudinal and cross-national perspectives, the mechanisms behind the heterogeneous degrees of inequality across societies remain elusive. As mentioned, educational tracking has been seen as a key societal determinant. However, OECD (2018) reveals that the magnitude of SES significantly varies even among HPS with similar levels of tracking and higher education expansion. This suggests there are missing societal traits, not yet explored in prior studies, that explain cross-national variation in the extent of educational inequality. Identifying this “hidden” structure would also be valuable from a policy perspective in addressing unequal educational attainment in HPS.

In this regard, recent research has detected a unique social structure: (1) the expansion of higher education (i.e., educational expansion) is not identical to the accumulation of high skills (i.e., skills diffusion) and (2) these two societal dimensions play distinct roles in social stratification by influencing the amount and allocation of human capital and socio-economic rewards (Araki, 2020; Araki & Kariya, 2022; Hanushek & Woessmann, 2015).1 Drawing on these findings, Araki (2023b) proposed the “EE-SD model” to uncover the characteristics of higher education systems and relevant social problems. This framework, with close attention to skills alongside education per se, potentially offers a useful viewpoint to better understand educational stratification in HPS for two reasons.

First, given that high-SES families tend to transmit their high educational attainment via human capital development of offsprings in terms of high skills and aspirations (Davies et al., 2014), this relative advantage may weaken due to skills diffusion insofar as this societal shift occurs in a way that promotes the share of the population possessing high skills across social strata including the disadvantaged. This also means, so long as skills diffusion is realized exclusively among the advantaged without involving their low-SES counterparts, the degree of educational inequality may even intensify due to the exacerbated advantage of the high-SES group in human capital formation.

Second, in case skills diffusion promotes a more meritocratic rewards allocation process based on increased visibility of skills (Araki, 2020), it is plausible that the relative impact of family background on educational attainment diminishes while the importance of skills as such increases. Put differently, if HPS are formed merely as a consequence of expanding educational opportunities without skills diffusion, the advantaged may retain their prestigious positions on the education ladder regardless of their skills level. Furthermore, considering a possibility that the accumulation of high skills in a society does not make skills more visible, skills diffusion may not affect the structure of educational inequality due to the absence of skills-based meritocratic system. In either case, the association between intergenerational transmission of higher education and societal-level skills diffusion represents an essential knowledge gap in this vein.

From a comparative perspective, this paper thus examines how the linkage between SES and college completion varies across societies depending on the degree of skills diffusion, as well as higher education expansion and tracking. In what follows, the relevant literature is reviewed, followed by data/methods, analysis results, and discussion.

Inequality in educational attainment

In analyzing the association between individuals’ SES and educational attainment, scholars have long paid attention to how it shifts in tandem with educational expansion (Breen, 2010; Shavit et al., 1993). This agenda is particularly relevant in the contemporary world, many parts of which have achieved HPS with tertiary enrolment ratios exceeding 50% (Cantwell et al., 2018; Marginson, 2016a).

One oft-cited concept in this line of research is maximally maintained inequality (MMI) proposed by Raftery and Hout (1993), although their primary focus was on secondary rather than tertiary education. Uncovering that the contribution of social origin to children’s education persisted despite increased educational opportunities in Ireland, they argued intergenerational inequality would only begin to decline once the advantaged reached a saturation point (e.g., 100% of enrolment). Subsequent studies have widely confirmed this MMI structure at the tertiary education level (Bar Haim & Shavit, 2013; Chesters & Watson, 2013; Czarnecki, 2018; Konstantinovskiy, 2017; Wakeling & Laurison, 2017).

Extending MMI, Lucas (2001) found that inequality had been effectively maintained, as advantaged individuals would secure valuable educational assets (e.g., prestigious institutions and fields of study) even when the disadvantaged caught up in terms of the level of educational qualifications. A vast literature has empirically supported the idea of effectively maintained inequality (EMI) in the higher education sector across the globe (Ayalon & Yogev, 2005; Boliver, 2011; Dias Lopes, 2020; Ding et al., 2021; Gerber & Cheung, 2008; Hällsten & Thaning, 2018; Kopycka, 2021; Reimer & Pollak, 2010; Seehuus, 2019; Torche, 2011; Triventi, 2013).

Meanwhile, introducing a standardized analytical model, Breen et al. (2009) argued that the link between origins and educational attainment weakened along with educational expansion in multiple countries. Much research reports a similar structure of nonpersistent inequality (Barone & Ruggera, 2018; Breen, 2010; Breen et al., 2010; Duru-Bellat & Kieffer, 2000; Pfeffer & Hertel, 2015). In line with these longitudinal findings, comparative work also detected the smaller social gap in education in societies with a larger share of highly educated populations, despite the observed MMI structure in each country (Liu et al., 2016).

In investigating the mechanisms behind cross-national variation in the SES effect on educational attainment, scholars have shed light on institutional stratification in education (Pfeffer, 2008). Evidence shows that (1) highly tracked systems make education-work transitions more effective (i.e., learners gain occupation-specific skills or at least educational credentials signifying those skills, thus obtaining occupations relevant to their fields of study) (Bol et al., 2019) but (2) strong tracking also intensifies educational inequality compared to more comprehensive education systems (Bol and van de Werfhorst, 2013; Burger, 2016; Chmielewski et al., 2013; Österman, 2018; Reichelt et al., 2019; Tieben & Wolbers, 2010; Van de Werfhorst, 2018; Van de Werfhorst and Mijs, 2010).

The link between SES and educational attainment has thus been uncovered in relation to societal-level educational expansion and tracking. Nonetheless, one puzzling fact is that the degree of inequality significantly varies even among HPS with similar social policies and education systems (OECD, 2018). It is plausible that some societal traits, which have been inadequately incorporated in prior studies, operate in forming educational inequality.

As argued, one potentially important process here is skills diffusion. Evidence shows (1) the degree of skills diffusion is positively correlated with that of educational expansion, making HPS more likely to advance skills diffusion (Araki, 2023b) but (2) the effects of educational expansion and skills diffusion on socio-economic outcomes at the individual and societal levels are not identical (Araki, 2020; Hanushek & Woessmann, 2015). Given these arguments, one may assume that the accumulation of high skills in a society, apart from educational proliferation, plays a unique role in forming educational (in)equality especially via two possible mechanisms.

First, prior research argues that skills diffusion may accelerate the skills-based rewards distribution because of increased discernability of high skills, which allows the labor market to identify highly skilled human resources (Araki, 2020). Should this intensified meritocratic mechanism induced by skills diffusion be applicable to the schooling process, the impact of SES on educational attainment may diminish in contrast to the growing importance of high skills. Nonetheless, evidence is elusive concerning the extent to which skills diffusion actually increases skills’ visibility in such a way that educational assets are allocated based on skills instead of SES. Put differently, it is still possible that the structure of educational inequality is not affected, or rather exacerbated, by skills diffusion.

Second, the accumulation of high skills, especially among the disadvantaged, may mitigate the comparative advantage of high-SES groups in human capital formation. Considering that the advantaged are more likely to invest their resources to foster children’s skills, which are favored in the process of climbing the educational ladder, the effects of such interventions could be hindered by skills development among the disadvantaged group. One should note, despite this potential consequence of skills diffusion, SES may still exert its influence on education by exerting symbolic power in that children from advantaged families easily internalize legitimate culture and behaviors leading to better educational outcomes (Jæger & Karlson, 2018; Sieben & Lechner, 2019). In addition, in response to the catchup by low-SES groups, their high-SES counterparts may invest more to further enhance children’s skills both quantitatively and qualitatively (i.e., the level and type of skills, respectively). This perception is aligned with EMI theory on educational inequality.

Nevertheless, the SES gap incurred by unequal human capital formation could still diminish in association with skills diffusion. For example, Huber, Gunderson, and Stephens (2020) found that the skills development mechanism played a role in reducing inequalities, although their focus was on educational spending and income inequality. Should this be the case for the distribution of higher education opportunities, it is logical to assume that the cross-national variation in the linkage between SES and educational attainment can be explained partially, if not completely, by the extent of skills diffusion in each society. Indeed, while showing the typological EE-SD framework, Araki (2023b) argued that the structure of educational inequality would be an important agenda to be examined by incorporating both educational expansion and skills diffusion. Therefore, the current study investigates the heterogeneous SES effect on higher education attainment with particular attention to societal-level skills diffusion, educational expansion, and tracking.

Data and methods

Data and strategy

The degree of skills diffusion has long been unmeasurable in a comparable way. However, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has recently developed an international survey of adult skills (PIAAC), which permits a cross-national examination of cognitive skills. Although using this dataset merely covers OECD and partner countries, future research can use the framework and findings that follow as the foundation to investigate broader geographical areas.

PIAAC is composed of a standardized assessment of cognitive ability and background questionnaires including educational attainment and socio-demographic attributes. Participants are nationally representative individuals aged 16 to 65 and accordingly, one can infer the skills level of the population based on individual-level data (OECD, 2019). Because of its wide coverage of variables and high quality skills data, PIAAC has been used by the vast literature on educational inequality and socio-economic returns to education (Araki, 2020, 2023a; Hanushek et al., 2015; Heisig et al., 2020; Huber et al., 2020; Jerrim & Macmillan, 2015; Pensiero & Barone, 2024). One limitation of PIAAC is its scope: while it primarily assesses cognitive ability in terms of literacy and numeracy,2 other types (e.g., noncognitive and occupation-specific skills) are not directly included. However, given that cognitive skills serve as the basis for other dimensions of skills and socio-economic outcomes (Krishnakumar & Nogales, 2020; OECD, 2016), it is sensible to use the PIAAC data to quantify the skills level.

Among PIAAC participants aged 16 to 65, this article focuses on respondents aged 25 to 34, considering that the association between SES and education could significantly vary across cohorts. This approach also reduces two risks: (1) as compared to younger groups, respondents are likely to have completed the highest level of education; and (2) unlike older groups, the influence of work experience and relevant attributes on educational attainment is assumed to be small. From the OECD public use database,3 the current study extracts 32,549 respondents in 26 countries that provide valid data for all predictor and outcome variables as detailed below. See Table 1 for specific countries and the sample size with the gross tertiary enrolment ratio, which indicates that all countries are classifiable as HPS (i.e., over 50%).

One potential analytic approach here is to focus on how the contribution of SES to educational attainment has shifted over time in the process of educational expansion and skills diffusion in a given society. As reviewed, much research in this vein has employed a longitudinal approach to compare multiple cohorts within countries. Although this method gives detailed implications for each society, it does not completely address period effects (Glenn, 1976). In addition, because the strength of tracking is relatively stable (Brunello & Checchi, 2007), it is difficult to accurately detect the longitudinal change.

Two types of cross-country analyses thus become sound strategies. The first approach is to perform country-specific analyses using the individual-level data and to contrast the relative degree of educational inequality and societal-level degrees of educational expansion, skills diffusion, and tracking across cases. The second strategy is to employ hierarchical modeling with pooled data from all countries with both individual and country-level variables. While the first method provides evidence for each society, the second one shows the general tendency beyond the national boundary. Given the comparative advantage of these two options, both approaches are employed: (1) country-specific analyses using individual-level data in 26 countries and (2) multilevel regressions focused on the link between the strength of educational inequality and societal-level conditions.

Variables

The outcome variable is the possession of a bachelor’s degree or above, which is equivalent to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 2011 Level 6 and above. Although short-cycle tertiary education (ISCED 2011 Level 5) is sometimes included when assessing individuals’ educational attainment, the nature of this educational stage varies across countries (Di Stasio, 2017). To ensure international comparability, the current paper employs ISCED 2011 Level 6 and above as a measure for high educational attainment. Considering also (1) the potential bias incurred by using a categorical measure in hierarchical modeling and (2) the different nature between the possession of tertiary degrees and the length of educational experience, a continuous variable (i.e., years of schooling) is also adopted. Because one country does not provide data on this continuous measure, the nonlinear model (with the dummy for ISCED 2011 Level 6 and above) is primarily shown in the manuscript, while the linear model (with years of schooling as an outcome) is displayed as a robustness check (see the next section for more details).

As regards individual-level predictor variables, much research has used parental education, occupation, and economic status, as well as the number of books in the home (NBH). Among these, the PIAAC dataset includes parental education (i.e., father’s and mother’s highest levels of education) and NBH. Although NBH has been widely taken as a representative SES measure (Chmielewski, 2019; OECD, 2016; Sieben & Lechner, 2019), recent research points out its potential endogeneity problem especially when the respondents are children (Engzell, 2021). Considering also the meaning/value of NBH substantially varies across countries, the current study uses parental education to represent SES. This strategy focused on parental education is widely employed by the literature in this vein (Brand & Xie, 2010; Cheng et al., 2021; Oh & Kim, 2020; Pensiero & Barone, 2024; Torche, 2018). Following prior studies, three categories are constructed by combining paternal and maternal education (i.e., both parents, one parent, or neither parents are tertiary educated). Meanwhile, a robustness check is performed by replacing parental education with NBH, and the result is shown in the Appendix (Table 5). Note that the result of this supplementary analysis is consistent with the main findings that follow. Alongside parental education, individual-level predictors include gender (men dummy), age (30–34-year-old dummy),4 and immigrant background (first-generation immigrant dummy) as these attributes are substantially associated with educational attainment (Breen & Jonsson, 2005).

Country-level variables cover the levels of educational expansion, skills diffusion, and tracking. To align with the outcome variable, the education measure is the percentage of the population who possess a bachelor’s degree and above. Considering the potential bias caused by using the simple means of individual-level education and skills in the PIAAC dataset for macro-level indicators, the societal-level variables here are not estimated based on PIAAC micro data but extracted from the national statistics in each country (OECD, 2014). It is noteworthy that the following results and implications are robust even when replacing this societal trait with the proportion of people with a degree including ISCED 2011 Level 5 (short-cycle tertiary) (see Table 6 in the Appendix).

For the skills indicator, following previous research (Araki, 2020, 2023c), the proportion of individuals whose mean score of literacy and numeracy in PIAAC is 326 and above (out of 500 points) is used. This is consistent with the OECD’s definition of high skills (OECD, 2019). As discussed, “skills” directly assessed by PIAAC refer to cognitive ability, and therefore, future research must incorporate other dimensions to advance this line of studies. These macro-level education and skills metrics are limited to the population aged 25 to 34 in line with individual-level variables. This way, the marginal distribution of educational opportunities and skills among the target age group is properly incorporated in the following analyses. Note that this measure reflects the skills level among the population ages 25–34, and hence, it is suitable to test one of the said two hypothetical mechanisms: a more meritocratic rewards allocation process is intensified by skills diffusion, leading to less educational inequality. Meanwhile, the percentage of people with high skills among those whose parents are not tertiary educated is also used to examine the second scenario: the larger share of highly skilled people among low-SES groups undermines the comparative advantage of high-SES groups in human capital formation. This skills indicator for the low parental education group is estimated by the OECD using all participants in each country and not limited to those aged 25 to 34. The analysis results of this second approach are thus shown in the Appendix (Table 6).

The degree of tracking is derived from Bol and van de Werfhorst (2013). Admittedly, other conditions could also affect the association between parental education and educational attainment against a background of skills diffusion and educational expansion. In particular, the macroeconomic structure may alter the social function of skills and higher education, while the overall degree of social inequality may influence educational inequality. Although the aforementioned three societal-level traits are primarily used given the potential bias incurred by a larger number of macro-level measures against the relatively small sample size for countries, GDP per capita and the Gini index are therefore added to the main analysis for a robustness check (see the Appendix, Table 6). Table 2 summarizes descriptive statistics.

Analytic models

For country-specific analyses, binary logistic regression is performed using individual-level data for 26 countries respectively as follows.

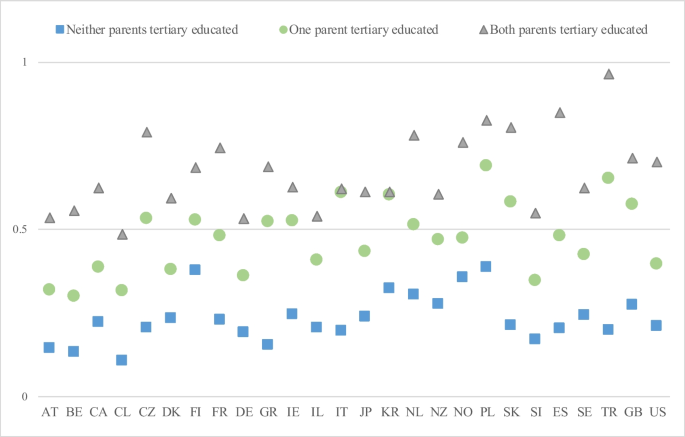

where i = individual, pi = the probability of holding a bachelor’s degree or above for individual i, bn = the coefficient of predictor variables, Mi = the men dummy, Ai = the age 30–34 dummy, Ii = the first-generation immigrant dummy, BTi = the dummy for those whose parents are both tertiary educated, OTi = the dummy for those having one tertiary educated parent, and εi = the residual for individual i. The primary focus here is on the parameters for parental education (b4 and b5). Given that these coefficients do not provide straightforward implications (Breen et al., 2018; Mood, 2010), the average marginal effects (i.e., predicted probability for each parental education group) are also estimated and compared across countries to confirm the variation in the advantage of having tertiary educated parents (see Fig. 1). This serves as the basis for the following multilevel regressions.

In model 1 of hierarchical modeling, only individual-level predictors are employed with particular attention to b4, and b5 in Eq. (2), where j = level two (i.e., country).

In models 2 to 4, three country-level variables and their interactions with two individual-level parental groups are added to model 1, respectively, to examine how the association between parental education and educational attainment varies in accordance with the societal conditions. Although there is a risk of biased estimation by including more than two level-two variables given the limited number of countries in the current model, model 5 concurrently incorporates the extent of educational expansion, skills diffusion, and tracking to confirm the robustness of models 2 to 4. GDP per capita and the Gini index are further added for robustness checks (see Table 6 in the Appendix). The basic concepts of these models are describable as follows.

where γ00 = the average intercept, γ0n = the coefficient of country-level predictor variables X, and u0j = the country (j)-dependent deviation. Substituting Eq. (3) into Eq. (2) and denoting bn by γn0 while incorporating cross-level interaction terms, γ4n and γ5n in Eq. (4) below indicate the heterogeneous magnitudes of two parental education measures associated with three societal traits. Following the recent argument that random slopes on lower-level variables used in cross-level interactions should be incorporated (Heisig & Schaeffer, 2019), both random intercepts and slopes are estimated for parental education as follows.

where unj = the country dependent deviation of the slopes for two parental education groups. Finally, as shown in Eq. (5) where Yij is years of schooling for individual i in country j, model 6 employs a multilevel linear regression approach with the same predictors as model 5 for a robustness check.

Note that these cross-sectional models do not completely account for unobserved variables at the individual and societal levels. As the OECD has been administering the second cycle of PIAAC, future research must undertake longitudinal analyses to address this issue.

Results

Table 3 shows the results of binary logistic regression of college completion for 26 countries. In all cases, parental education exhibits a positive sign for the chance of attaining tertiary education (i.e., b4 and b5 in Eq. 1 are positive and statistically significant).5 In particular, the magnitude is notably large for the most advantaged group with both parents being tertiary educated (e.g., b4 = 1.02, 95%CI 0.63 to 1.41; b5 = 1.92, 95%CI 1.43 to 2.42 in Austria). Figure 1 indeed indicates that the predicted probability of obtaining a first degree substantially varies across three parental education groups, with the most disadvantaged tier (i.e., without tertiary educated parents) suffering from a limited chance of completing tertiary education in every country.

Predicted probability of completing tertiary education by parental education in 26 countries. The Y axis indicates the predicted probability of attaining tertiary education (ISCED 2011 level 6 or above) for three parental education groups as indicated at the top of the figure across 26 countries (X axis). See also Table 1 for country abbreviations

Nonetheless, it is worth noting that despite the relative disadvantage within a country, the predicted probability of college completion among the low parental education group in some countries (e.g., 37.6%, 95%CI 33.9 to 41.3 in Finland) is higher than that of the second tier with one tertiary educated parent in others (e.g., 29.8%, 95%CI 22.7 to 36.9, in Belgium). In addition, as far as the extent of educational inequality is concerned, the gap in the chance of college completion between the most advantaged and disadvantaged groups differs across nations, ranging from 28.8 points in South Korea to 76.6 points in Turkey. The key question here is how this cross-national variation in intergenerational transmission of higher education is associated with societal-level conditions.

Table 4 summarizes the results of multilevel regressions. In model 1 with only individual-level variables, all predictors show a significant sign for educational attainment at the 0.1% level. That is, even when accounting for gender, age, and immigrant background, as well as cross-national differences in the intercept and slopes, the strong association between parental education and educational attainment is confirmed. As observed earlier in the country-specific analyses, the magnitude of having two tertiary educated parents is larger than that of only one highly educated parent (γ40 = 1.91, 95%CI 1.73 to 2.08; γ50 = 1.08, 95%CI 0.95 to 1.21). This substantial linkage between parental education, especially having two tertiary educated parents, and the chance of college completion holds regardless of models in the following analyses.

Model 2 adds one country-level variable (i.e., the proportion of tertiary educated people) and its cross-level interactions with two measures for parental education. Apart from the significant coefficients of individual-level predictors, the interaction terms between parental education and the degree of educational expansion shows negative and statistically significant signs (γ41 = −0.02, 95%CI −0.04 to 0.00, P = 0.022; γ51 = −0.02, 95%CI −0.04 to −0.01, P = 0.006). This suggests, as argued by some prior studies, the advantage of having tertiary educated parents is likely to be smaller in societies where the aggregate education level is relatively high. Put differently, although further longitudinal investigations are necessary to establish causality, the accumulation of educational opportunities in a society might operate as an equalizer in mitigating the influence of parental education.

An identical structure is observed in model 3, where the degree of educational expansion is replaced with that of skills diffusion (i.e., the proportion of highly skilled people). In addition to the significant links between individual-level predictors and the probability of obtaining a first degree, the coefficient of the interaction terms between parental education and the societal-level skills indicator is negative (γ42 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.05 to −0.01, P = 0.003; γ52 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.05 to −0.02, P < 0.001). As with the extent of educational expansion, this result indicates a possibility that the role of parental education in children’s educational attainment could decline in societies with a higher degree of skills diffusion. In Model 4, the strength of tracking is included instead of societal-level education and skills measures. As reported by previous research in this vein, the positive signs of interaction terms between tracking and parental education are confirmed (γ43 = 0.15, 95%CI −0.02 to 0.31, P = 0.088; γ53 = 0.15, 95%CI 0.04 to 0.27, P = 0.007). That is, the extent of intergenerational educational inequality is likely to be stronger in more tracked systems.

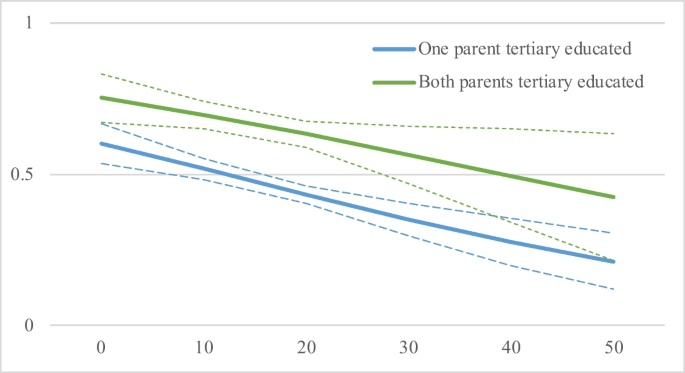

Model 5 incorporates all three country-level predictors and their interaction terms. One important result here is that the interaction between parental education and the degree of educational expansion is almost nullified (γ41 = −0.00, 95%CI −0.03 to 0.02, P = 0.773; γ51 = 0.01, 95%CI −0.01 to 0.02, P = 0.326). In contrast, the one between parental education and the skills diffusion measure holds its negative sign (γ42 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.05 to −0.00, P = 0.030; γ52 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.05 to −0.02, P < 0.001). The same structure is observed when (1) conducting multilevel linear regression with years of schooling as the outcome in Model 6 (γ41 = −0.04, P = 0.133; γ51 = −0.01, P = 0.453; γ42 = −0.04, P = 0.072; γ52 = −0.05, P = 0.001), (2) incorporating the proportion of people with short-cycle tertiary education for the educational expansion metric in Model A2 (γ42 = −0.02, 95%CI −0.04 to 0.00, P = 0.034; γ52 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.04 to −0.02, P < 0.001), and (3) adjusting for GDP per capita and the Gini index as additional societal-level conditions in Model A3 (γ42 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.06 to 0.00, P = 0.059; γ52 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.04 to −0.01, P < 0.001). Figure 2 indeed depicts the diminishing effect of parental education in tandem with higher proportions of the population with high skills.

Marginal effects of parental education by the degree of skill diffusion. The Y axis is the marginal effects of parental education (i.e., one parent is tertiary educated; both parents are tertiary educated) across the degree of skills diffusion (i.e., the percentage of population with high skills) ranging from 0 to 50 (X axis) based on the multilevel binary logistic regression (model 5). The dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals

The sole exception is the final model using the share of highly skilled people among the low parental education group as the societal-level skills measure (Model A4 in the Appendix, Table 6). While its interaction with the second tier (i.e., only one tertiary educated parent) shows a substantially negative coefficient (γ52 = −0.02, 95%CI −0.04 to −0.01, P = 0.001), the one with the top tier (i.e., both parents are tertiary educated) is not statistically significant despite its negative sign (γ42 = −0.02, 95%CI −0.04 to −0.00, P = 0.106). This suggests that the second hypothetical scenario (i.e., the advantage of high-SES groups in human capital formation diminishes along with skills diffusion among the disadvantaged) is partially supported in that the second layer in parental education with one tertiary educated parent encounters their diminishing advantage in educational attainment. However, the most advantaged group seems to retain their relative position even when the disadvantaged advances their cognitive skills. In the next section, after summarizing the key findings, some implications are discussed.

Discussion and conclusion

This study investigates cross-national variation in intergenerational transmission of education among high participation systems (HPS). Drawing on the EE-SD framework (Araki, 2023b), particular attention is paid to societal-level higher education expansion, tracking, and skills diffusion. Using the OECD PIAAC data for 32,549 adults in 26 countries, individual-level analyses first corroborate the literature in that parental education is significantly associated with the likelihood of college completion. However, multilevel regressions show that educational inequality is not persistent; rather, the advantage of having tertiary educated parents becomes smaller in societies with a higher proportion of tertiary graduates. This result supports prior evidence indicating the equalizing function of educational expansion.

Nevertheless, once incorporating the degrees of skills diffusion and tracking as societal-level predictors, the interaction between the extent of educational expansion and parental education loses its significant sign. Instead, the skills indicator holds a negative interaction effect with parental education. Further research is necessary to claim causation, given that (1) unobserved societal traits may be significantly affecting the link between parental education and the societal-level education/skills indicators and (2) the degree of skills diffusion may mediate the effect of educational expansion as detailed below. Yet, based on these results, it is plausible that the accumulation of high skills in a society plays a role in altering the power of parental education over children’s chance of attaining higher education.

Assuming that the observed results reflect a causal relationship to a certain extent, they are interpretable as representing distinct functions of educational expansion and skills diffusion. When focusing solely on the proliferation of educational opportunities (as in model 2), growth in higher education appears to operate as an equalizer and mitigates intergenerational transmission of higher education. However, because educational expansion and skills diffusion often advance hand in hand (Araki, 2023b), the seemingly equalizing effect of educational expansion might actually be attributed to the contribution of skills diffusion. Consequently, the observed effect of educational proliferation can be cancelled out once the skills dimension is taken into account. Importantly, this does not necessarily mean that educational expansion is irrelevant to the heterogeneous link between parental education and children’s educational attainment, as skills diffusion may mediate the contribution of increased higher education opportunities. That is, educational expansion may indirectly reduce educational inequality via fostering high skills. Nonetheless, regardless of the extent to which skills diffusion incorporates the influence of educational proliferation, it is noteworthy that the accumulation of high skills itself is substantially associated with the degree of educational inequality.

As regards the potential mechanism whereby skills diffusion may curb intergenerational transmission of education, one must recognize the qualitative difference between two societal conditions. While educational expansion means the larger number/share of the population with a tertiary degree as such regardless of their actual skills, skills diffusion represents the accumulation of individuals with high skills in a society. Accordingly, the level of skills diffusion can signify the quantity of human resources possessing adequate abilities to make rational choices and contribute to a more meritocratic society, where educational and other assets may be allocated based on individuals’ merit rather than SES. This perception aligns with prior studies that have demonstrated the distinct roles of skills in the rewards allocation process (Araki & Kariya, 2022; Hanushek et al., 2015). Importantly, this diminishing inequality cannot be observed solely through educational expansion, as it does not guarantee a sufficient number of individuals with high skills who can effectively promote the establishment of a meritocratic mechanism.6

Should this be the case, the extent of intergenerational transmission of education is likely to diminish especially when skills diffusion occurs among low-SES groups. This is because the accumulation of high skills among the disadvantaged undermines the relative advantage of high-SES groups (e.g., those with tertiary educated parents in the current analysis) in the human capital formation process, which in turn affects their chance of college completion. Notwithstanding, the empirical findings (model A4 in the Appendix, Table 6) only partially support this hypothesis. In tandem with the higher proportion of high skills among the disadvantaged whose parents are not tertiary educated, the advantage of having one tertiary educated parent declines. However, the advantageous position of having both a tertiary educated mother and father is not significantly devalued despite the negative sign. This suggests that the catching-up effect of advancing cognitive skills among the disadvantaged is more likely to be observable against the second tier of parental education strata, whereas the most advantaged group may maintain their higher chance of college completion, at least in the initial stage. These trends, which demonstrate persistent and flexible advantages among the socially privileged, are consistent with MMI (Raftery & Hout, 1993) and EMI (Lucas, 2001). If in fact this partial equalizing effect of skills diffusion exists, it raises an important question: will further advancement of skills development among the disadvantaged eventually mitigate the advantageous position of the top tier? In particular, from the EMI perspective, it is worth exploring whether the advantaged group will maintain their superiority by targeting certain fields of study favored in the labor market, particular higher education institutions with high prestige, and/or further advanced degrees (e.g., master’s and doctoral levels). Longitudinal studies are essential to answer these questions.

As such, one can better understand cross-national variation in educational inequality by shedding light on the diffusion of high skills, as well as higher education. This also suggests that the contradictory views on the effect of educational expansion in the literature (i.e., persistent versus nonpersistent inequality) may partially reflect the extent to which each study incorporates the influence of skills diffusion. When analyzing the consequences of increased educational opportunities, research may find a declining contribution of SES to educational attainment so long as educational proliferation in the target case is accompanied by skills diffusion (i.e., when trends in aggregate levels of education and skills are aligned). In contrast, if one focuses on societies (or periods/cohorts) where these two societal traits are significantly decoupled and educational opportunities increase without corresponding skills diffusion, the unequal structure is likely to persist because the equalizing role of skills diffusion is absent.

Nevertheless, the current paper adopts a cross-country approach unlike much research in this vein. Therefore, further examination is imperative to conclude whether, to what extent, and how skills diffusion actually operates as a fundamental societal trait. First, country-specific longitudinal analyses are pivotal to detect causal relationships across SES, higher education attainment, skills diffusion, and other factors. Second, in addition to the retrospective approach used in this paper, prospective analyses are essential lest we overrate the degree of intergenerational inequality (Breen & Ermisch, 2017; Lawrence & Breen, 2016; Song & Mare, 2015). Third, variables should be extended for family background (e.g., parental skills, occupations, and income), educational outcomes (e.g., aspiration, completion, fields of study, and prestige of institutions), skills (e.g., noncognitive and occupation-specific skills), and societal conditions (e.g., labor and welfare policy). Because the values of specific types of educational credentials and skills may differ in accordance with macroeconomic and socio-cultural settings, interactional effects of these variables need to be carefully examined. Likewise, given that the metrics for individual-level education and skills and societal-level educational expansion and skills diffusion are closely linked in the current study (and thus estimation could be somewhat biased), future research must incorporate different types of education and skills measures at the individual and societal levels. Fourth, as an extension of this line of studies, one should investigate how the trend of educational expansion and skills diffusion affect not only educational attainment but also (in)equalities in socio-economic outcomes beyond the schooling stage. This is particularly important as recent research shows that educational equalization does not necessarily result in the weakening linkage between parental education and children’s earnings over time, except Scandinavian countries (Pensiero & Barone, 2024). Finally, in addressing these tasks, analyses of non-OECD and non-HPS cases would be useful to obtain insights from a comparative perspective.

With this potential for further development, the present study contributes to advancing our knowledge on educational inequality among HPS. It is particularly noteworthy that the accumulation of high skills, along with the expansion of higher education opportunities, may collectively operate as an equalizer and mitigates intergenerational inequality in educational attainment.

Notes

-

1.

Terms “educational expansion” and “skills diffusion” imply longitudinal changes in a given society, that is, an increase in the number/share of individuals with higher levels of educational attainment and skills, respectively. Meanwhile, macro-level data in the following empirical analyses are collected at one point in time. Therefore, the “levels of education/skills” are used in some of the empirical part, but the terms “educational expansion” and “skills diffusion” are also employed unless this strategy violates the accuracy of arguments.

-

2.

Although PIAAC also assesses ICT skills, this article focuses on literacy and numeracy because some countries do not provide available data on ICT skills.

-

3.

See the OECD website for the PIAAC data (https://webfs.oecd.org/piaac/puf-data/) [Accessed: August 1, 2023]. Some countries listed in this webpage are not included in the following analyses due to the absence of comparable data for tracking.

-

4.

This dummy variable is employed instead of the continuous age measure because an ample number of respondents have only age group information in the PIAAC public-use dataset.

-

5.

The analysis also reveals the nuanced function of other predictors including gender, age, and immigrant background. Although the primary focus of this article is on parental education, future research will benefit from investigating how and why the association between educational attainment and these attributes varies across societies.

-

6.

Another supposition is that the accumulation of high skills merely enhances the importance of other types of family background, such as parental occupations and economic class. Should this be the case, skills diffusion does not necessarily promote a meritocratic system even though the effect of parental education per se diminishes. This is an important agenda for future research.

Data availability

Data are available from the OECD website: https://webfs.oecd.org/piaac/puf-data/

Code availability

Available upon request.

References

Araki, S. (2020). Educational expansion, skills diffusion, and the economic value of credentials and skills. American Sociological Review, 85(1), 128–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419897873

Araki, S. (2023a). Beyond ‘imagined meritocracy’: Distinguishing the relative power of education and skills in intergenerational inequality. Sociology, 57(4), 975–992. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385231156093

Araki, S. (2023b). Beyond the high participation systems model: Illuminating the heterogeneous patterns of higher education expansion and skills diffusion across 27 countries. Higher Education, 86(1), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00905-w

Araki, S. (2023c). Life satisfaction, skills diffusion, and the Japan paradox: Toward multidisciplinary research on the skills trap. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 64(3), 278–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207152221124812

Araki, S., Kariya, T. (2022). Credential inflation and decredentialization: Re-examining the mechanism of the devaluation of degrees. European Sociological Review, 38(6), 904–919. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcac004

Ayalon, H., Yogev, A. (2005). Field of study and students’ stratification in an expanded system of higher education: The case of Israel. European Sociological Review, 21(3), 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci014

Bar Haim, E., Shavit, Y. (2013). Expansion and inequality of educational opportunity: A comparative study. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 31, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2012.10.001

Barone, C., Ruggera, L. (2018). Educational equalization stalled? Trends in inequality of educational opportunity between 1930 and 1980 across 26 European nations. European Societies, 20(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2017.1290265

Bol, T., van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2013). Educational systems and the trade-off between labor market allocation and equality of educational opportunity. Comparative Education Review, 57(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1086/669122

Bol, T., Ciocca Eller, C., van de Werfhorst, H. G., DiPrete, T. A. (2019). School-to-work linkages, educational mismatches, and labor market outcomes. American Sociological Review, 84(2), 275–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419836081

Boliver, V. (2011). Expansion, differentiation, and the persistence of social class inequalities in British higher education. Higher Education, 61(3), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9374-y

Brand, J. E., Xie, Y. (2010). Who benefits most from college? Evidence for negative selection in heterogeneous economic returns to higher education. American Sociological Review, 75(2), 273–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122410363567

Breen, R. (2010). Educational expansion and social mobility in the 20th century. Social Forces, 89(2), 365–388. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0076

Breen, R., Ermisch, J. (2017). Educational reproduction in Great Britain: A prospective approach. European Sociological Review, 33(4), 590–603. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx061

Breen, R., Jonsson, J. O. (2005). Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122232

Breen, R., Luijkx, R., Müller, W., & Pollak, R. (2009). Nonpersistent inequality in educational attainment: Evidence from eight European countries. American Journal of Sociology, 114(5), 1475–1521. https://doi.org/10.1086/595951

Breen, R., Luijkx, R., Müller, W., Pollak, R. (2010). Long-term trends in educational inequality in Europe: Class inequalities and gender differences. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp001

Breen, R., Karlson, K. B., Holm, A. (2018). Interpreting and understanding logits, probits, and other nonlinear probability models. Annual Review of Sociology, 44, 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041429

Brunello, G., Checchi, D. (2007). Does school tracking affect equality of opportunity? New international evidence. Economic Policy, 22(52), 782–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2007.00189.x

Burger, K. (2016). Intergenerational transmission of education in Europe: Do more comprehensive education systems reduce social gradients in student achievement? Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 44, 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2016.02.002

Cantwell, B., Marginson, S., Smolentseva, A. (2018). High participation systems of higher education. Oxford University Press

Cheng, S., Brand, J. E., Zhou, X., Xie, Y., Hout, M. (2021). Heterogeneous returns to college over the life course. Science Advances, 7(51), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abg7641

Chesters, J., Watson, L. (2013). Understanding the persistence of inequality in higher education: Evidence from Australia. Journal of Education Policy, 28(2), 198–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.694481

Chmielewski, A. K. (2019). The global increase in the socioeconomic achievement gap, 1964 to 2015. American Sociological Review, 84(3), 517–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419847165

Chmielewski, A. K., Dumont, H., & Trautwein, U. (2013). Tracking effects depend on tracking type: An international comparison of students’ mathematics self-concept. American Educational Research Journal, 50(5), 925–957. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831213489843

Czarnecki, K. (2018). Less inequality through universal access? Socioeconomic background of tertiary entrants in Australia after the expansion of university participation. Higher Education, 76(3), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0222-1

Davies, P., Qiu, T., Davies, N. M. (2014). Cultural and human capital, information and higher education choices. Journal of Education Policy, 29(6), 804–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2014.891762

Di Stasio, V. (2017). Who is ahead in the labor queue? Institutions’ and employers’ perspective on overeducation, undereducation, and horizontal mismatches. Sociology of Education, 90(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040717694877

Dias Lopes, A. (2020). International mobility and education inequality among Brazilian undergraduate students. Higher Education, 80(4), 779–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00514-5

Ding, Y., Wu, Y., Yang, J., & Ye, X. (2021). The elite exclusion: Stratified access and production during the Chinese higher education expansion. Higher Education, 82(2), 323–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00682-y

Duru-Bellat, M., Kieffer, A. (2000). Inequalities in educational opportunities in France: Educational expansion, democratization or shifting barriers? Journal of Education Policy, 15(3), 333–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930050030464

Engzell, P. (2021). What do books in the home proxy for? A cautionary tale. Sociological Methods and Research, 50(4), 1487–1514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124119826143

Gerber, T. P., Cheung, S. Y. (2008). Horizontal stratification in postsecondary education: Forms, explanations, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134604

Glenn, N. D. (1976). Cohort analysts’ futile quest: Statistical attempts to separate age, period and cohort effects. American Sociological Review, 41(5), 900–904.

Hällsten, M., Thaning, M. (2018). Multiple dimensions of social background and horizontal educational attainment in Sweden. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 56, 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2018.06.005

Hanushek, E. A., Schwerdt, G., Wiederhold, S., Woessmann, L. (2015). Returns to skills around the world: Evidence from PIAAC. European Economic Review, 73, 103–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.10.006

Hanushek, E. A., Woessmann, L (2015) The knowledge capital of nations: Education and the economics of growth. The MIT Press

Heisig, J. P., Elbers, B., Solga, H. (2020). Cross-national differences in social background effects on educational attainment and achievement: Absolute vs. relative inequalities and the role of education systems. Compare, 50(2), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2019.1677455

Heisig, J. P., Schaeffer, M. (2019). Why you should always include a random slope for the lower-level variable involved in a cross-level interaction. European Sociological Review, 35(2), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy053

Huber, E., Gunderson, J., Stephens, J. D. (2020). Private education and inequality in the knowledge economy. Policy and Society, 39(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2019.1636603

Jæger, M. M., Karlson, K. (2018). Cultural capital and educational inequality A counterfactual analysis. Sociological Science, 5, 775–795. https://doi.org/10.15195/V5.A33

Jerrim, J., Macmillan, L. (2015). Income inequality, intergenerational mobility, and the great gatsby curve: Is education the key? Social Forces, 94(2), 505–533. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sov075

Konstantinovskiy, D. L. (2017). Expansion of higher education and consequences for social inequality (the case of Russia). Higher Education, 74(2), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0043-7

Kopycka, K. (2021). Higher education expansion, system transformation, and social inequality. Social origin effects on tertiary education attainment in Poland for birth cohorts 1960 to 1988. Higher Education, 81(3), 643–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00562-x

Krishnakumar, J., Nogales, R. (2020). Education, skills and a good job: A multidimensional econometric analysis. World Development, 128, 104842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104842

Lawrence, M., Breen, R. (2016). And their children after them? The effect of college on educational reproduction. American Journal of Sociology, 122(2), 532–572. https://doi.org/10.1086/687592

Liu, Y., Green, A., Pensiero, N. (2016). Expansion of higher education and inequality of opportunities: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 38(3), 242–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1174407

Lucas, S. R. (2001). Effectively maintained inequality: Education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1642–1690. https://doi.org/10.1086/321300

Marginson, S. (2016a). High participation systems of higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 87(2), 243–271. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2016.0007

Marginson, S. (2016b). The worldwide trend to high participation higher education: Dynamics of social stratification in inclusive systems. Higher Education, 72(4), 413–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0016-x

Mood, C. (2010). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp006

OECD. (2016). Skills matter: Further results from the survey of adult skills. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/23078731

OECD. (2018). A broken social elevator? OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301085-en

OECD. (2014). Education at a glance 2014: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing

OECD. (2019). The survey of adult skills: Reader’s companion, Third Edition. OECD Publishing

Oh, B., Kim, C. (2020). Broken promise of college? New educational sorting mechanisms for intergenerational association in the 21st century. Social Science Research, 86, 102375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.102375

Österman, M. (2018). Varieties of education and inequality: How the institutions of education and political economy condition inequality. Socio-Economic Review, 16(1), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwx007

Pensiero, N., Barone, C. (2024). Parental schooling, educational attainment, skills, and earnings: A trend analysis across fifteen countries. Social Forces, 102(4), 1288–1309. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soad144

Pfeffer, F. T. (2008). Persistent inequality in educational attainment and its institutional context. European Sociological Review, 24(5), 543–565. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn026

Pfeffer, F. T., Hertel, F. R. (2015). How has educational expansion shaped social mobility trends in the United States? Social Forces, 94(1), 143–180. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sov045

Raftery, A. E., Hout, M. (1993). Maximally maintained inequality: Expansion, reform, and opportunity in Irish education, 1921–75. Sociology of Education, 66(1), 41–62.

Reichelt, M., Collischon, M., & Eberl, A. (2019). School tracking and its role in social reproduction: reinforcing educational inheritance and the direct effects of social origin. British Journal of Sociology, 70(4), 1323–1348. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12655

Reimer, D., Pollak, R. (2010). Educational expansion and its consequences for vertical and horizontal inequalities in access to higher education in West Germany. European Sociological Review, 26(4), 415–430. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp029

Seehuus, S. (2019). Social class background and gender-(a)typical choices of fields of study in higher education. British Journal of Sociology, 70(4), 1349–1373. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12668

Shavit, Y., Blossfeld, H.-P (1993) Persistent inequality: Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries. Westview Press

Sieben, S., Lechner, C. M. (2019). Measuring cultural capital through the number of books in the household. Measurement Instruments for the Social Sciences, 2(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42409-018-0006-0

Song, X., Mare, R. D. (2015). Prospective versus retrospective approaches to the study of intergenerational social mobility. Sociological Methods and Research, 44(4), 555–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114554460

Tieben, N., Wolbers, M. H. J. (2010). Transitions to post-secondary and tertiary education in the Netherlands: A trend analysis of unconditional and conditional socio-economic background effects. Higher Education, 60(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9289-7

Torche, F. (2011). Is a college degree still the great equalizer? Intergenerational mobility across levels of schooling in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 117(3), 763–807. https://doi.org/10.1086/661904

Torche, F. (2018). Intergenerational mobility at the top of the educational distribution. Sociology of Education, 91(4), 266–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040718801812

Traini, C. (2022). The stratification of education systems and social background inequality of educational opportunity. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 63(1–2), 10–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207152211033015

Triventi, M. (2013). Stratification in higher education and its relationship with social inequality: A comparative study of 11 European countries. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 489–502. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcr092

Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2018). Early tracking and socioeconomic inequality in academic achievement: Studying reforms in nine countries. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 58, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2018.09.002

Van de Werfhorst, H. G., Mijs, J. J. B. (2010). Achievement inequality and the institutional structure of educational systems: A comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102538

Voss, K., Hout, M., George, K. (2022). Persistent inequalities in college completion, 1980–2010. Social Problems. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spac014

Wakeling, P., Laurison, D. (2017). Are postgraduate qualifications the ‘new frontier of social mobility’? British Journal of Sociology, 68(3), 533–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12277

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Takehiko Kariya, Richard Breen, Jan O. Jonsson, Herman van de Werfhorst, Cláudia Sarrico, and anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments and suggestions.

Funding

This research is supported by the Social Sciences Internal Seed Grant Scheme, the University of Hong Kong (000250635).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Araki, S. Assessing educational inequality in high participation systems: the role of educational expansion and skills diffusion in comparative perspective. High Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01232-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01232-y