Quick Links

Summary

- RoboCop's identity crisis and superhuman powers are balanced out by his mortal partner on the police force, Anne Lewis, who protests against OCP in more traditional ways.

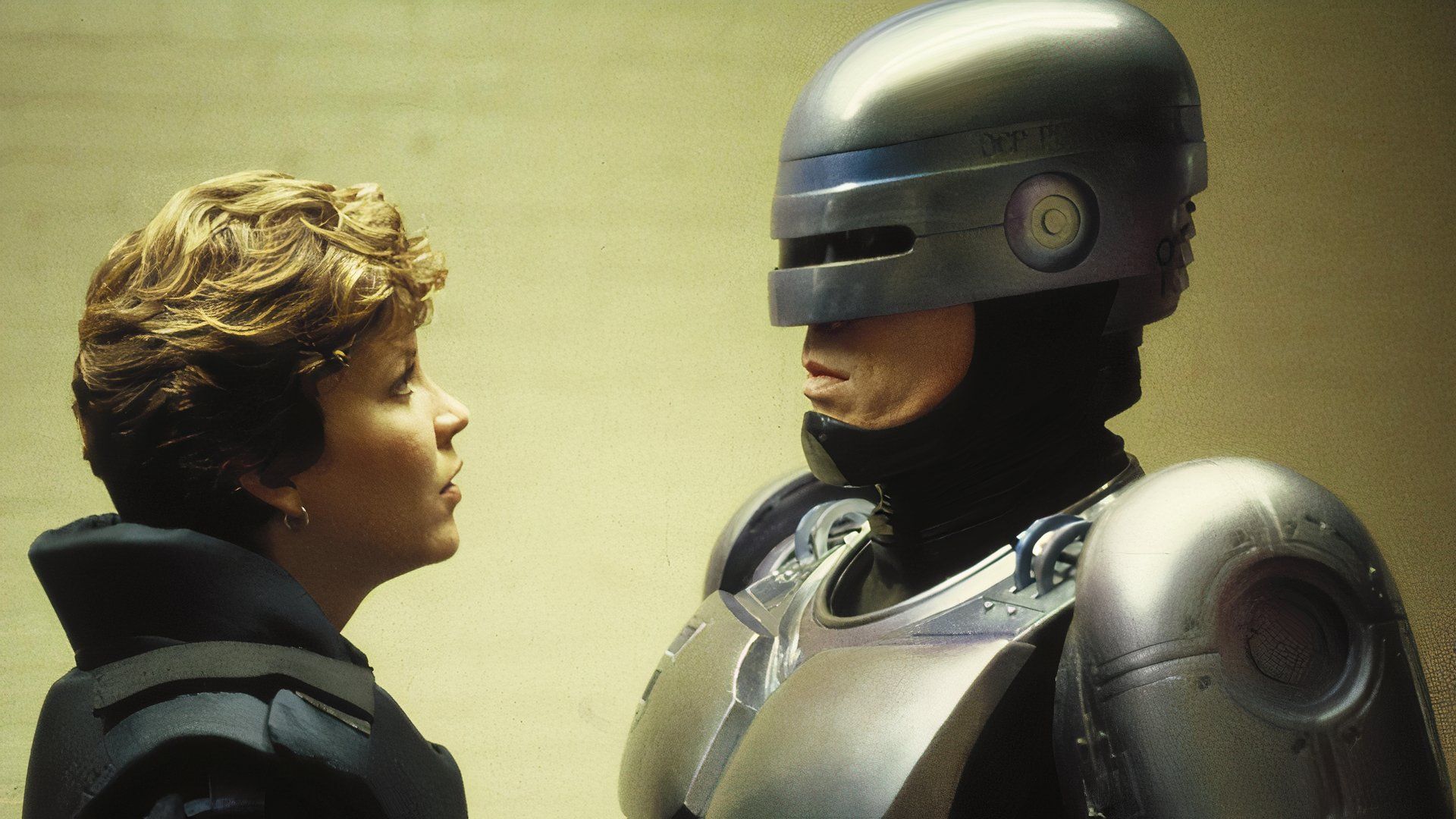

- The film averts traditional tropes by creating a partnership between RoboCop and Officer Lewis that is deeply empathetic, and even playful, and yet completely non-sexual.

- Murphy and Lewis contrast the primary antagonists of the series, the OCP corporation, the two police officers immune to corruption or intimidation in a city where drug-addicted psychos are on the OCP's health plan.

When the script for RoboCop landed on Paul Verhoeven's desk in the mid-'80s, he initially saw it as an insult. He didn't see much value in the surface-level stuff, the cop drama shtick was merely a vehicle for some dehumanizing body horror and a critique of modern American society where profit always comes first. He wanted to make a sarcastic parable where law and order are meted by a corrupt corporation in a decaying Detroit beyond salvation from any mortal man. That same corporation (Omni Consumer Products) ironically seeks to destroy a machine (formerly a cop named Alex Murphy) that functions too well at police work, accidentally exposing all the secrets that were supposed to remain secret.

It's a neat, if simplistic, set-up. However, in a city full of degeneracy, sociopathic behavior, and hypocrisy, RoboCop stands out as an alarming figure, a man with unshakable moral conviction and inhuman restraint. The renegade cop with a heart of gold cliché dates back to the time of Dirty Harry and Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle, but in the RoboCop films (mostly the first one), it is flipped on its head, the police bought and paid for. For once, a movie ethically justifies a rogue cop plot. Loyally by the cyborg's side through three movies is his partner, Anne Lewis, the pair at war as often against Detroit's criminal element as their own conflicted superiors in the Detroit police force.

One thing that is notably missing from the films (and we don't mean the lack of a good script in RoboCop 3), is any trace of sexual tension whatsoever between the two co-workers. There were pretty rigid designated feminine roles in these kinds of films in 1987, but writers Ed Neumeier & Michal Miner and director Verhoeven depict Murphy and Lewis as equals, their relationship predicated only on mutual respect and a sense of duty. Viewers at the time likely would have expected a romance sub-plot to have arisen, but the director didn't have time for that kind of predictable, sappy sentimentality. The closest to a touching embrace that Verhoeven could muster for the two cops was when Lewis helps Murphy recalibrate his aiming mechanism when his gyros are knocked out of alignment.

More Than a Sidekick

Gory movies about cops out for revenge are a dime a dozen. A movie about a cyborg going on a revenge killing spree is likewise merely shlock without the human element underneath. RoboCop (the title character portrayed in the first two movies by Peter Weller) only works with the inclusion of a partner, played by Nancy Allen.

The working script created by Miner and Neumeier went through numerous permutations, as Neumeier had to convince the Dutch director why the film wasn't just another stupid action movie. In an interview with documentarian George Hickenlooper, Verhoeven admitted that he initially despised the script as a bad joke. Neumeier recalls arguing over the tone and satirical substance of the story, Verhoeven's wife finally winning him over by explaining the RoboCop/Murphy character as a modern-day Frankenstein:

"I only saw a very idiotic action movie, and I hate action and science fiction movies. But Orion asked me to take a second look at the script. They kept emphasizing that it was about the indestructibility of the human spirit, of the individual--a very American concept."

Unlike Frankenstein's Monster, Murphy rediscovers his humanity and true identity, saved from the OCP and the police on their payroll by Lewis. Interestingly, Lewis barely knew him, only assigned with him for one day before he was murdered. This is an important scene, not just because it's the turning point of the movie, but the moment she makes amends for her failure to save him earlier in the film. Her guilt at being bested by Clarence Boddicker's posse and her ongoing confrontations against the OCP's domination over the police force serves as lesser-appreciated aspects of the plot that are integral to understanding the overall context.

Sadly, the two sequels would retcon this upbeat ending of Murphy and Lewis cleaning up the city's corruption, as the OCP's redemption arc was tossed in the trash by RoboCop 2 writer Frank Miller. But that's a story for another day.

RoboDoc: The Creation of RoboCop Trailer Teases In-Depth Look at the 80s Classic

The new docuseries RoboDoc: The Creation of RoboCop will delve into the making of one of the most iconic movies of all time.Subverting All the Familiar Tropes

Pairing male and female counterparts together in the same police department plays out in painfully predictable ways in most media. Not here. Think Scully and Mulder from The X-Files, Booth and Brennan from Bones, Riggs and Cole from Lethal Weapon 3, or any number of hook-ups in Miami Vice, or NYPD Blue for examples to the contrary.

Modern viewers unaware of Nancy Allen's earlier filmography would be shocked to learn that she had launched her career as a typical horny teen in horror films, transitioning to an outright sex symbol by the time of 1980's Dressed to Kill. In RoboCop, she lacks any hint of traditional feminity, not even allowed to style her mandated haircut, which gets longer as Verhoeven is no longer around to yell at her. A scene where she removes her SWAT helmet to reveal long, flowing blonde locks was removed by Verhoeven for being too cheesy, according to Allen. As Allen told interviewers for the RoboCop Archive in later years, the role altered her career, but she wasn't aware just how much she'd have to adjust:

"Until then, no one had thought of me outside of the pretty, sexy, funny girl. ... It was a little confusing to people, in terms of who I was and what I did, in terms of the business of the business."

From a scathing attack on consumerism bleeding into a Jesus allegory and a nagging warning about cynicism in the face of urban decay, it's fair to say Verhoeven and company might have gone a little overboard with the messages. Yet, when it comes to the nuances of Murphy and Lewis' friendship, they didn't go out of their way to draw attention to it, which makes it that much more intriguing.

Kids wouldn't have noticed or cared about their platonic love, but grown-up viewers would have unconsciously sensed something awry. By the film's close, we've come to accept and prefer that they are not the slightest bit interested in each other. Perhaps the fact that Murphy had everything below his torso blasted off played a part in that choice, tough to say. He's still longing for a woman (his wife) who considers him deceased, playing up his tragic nature as neither human nor machine.

Robocop: Comic Book Movie, Comedic Satire, Terminator Rip-Off, or an Amazing Anomaly?

RoboCop is one of the most beloved movies of all time. But how did it evolve from production line to a walking, talking, killing machine?Murphy and Lewis vs the Military Industrial Complex

Murphy and Lewis are the lone figures, barring a few other cops in the Metro West Precinct, who can do the work that the OCP is trying to dominate through the privatization of law enforcement. As critic David Denby was wise to point out, the news clips that break up the narrative illustrate a world where "everyone has become desensitized" to violence, the arbitrary bureaucracy of corporations, and their overall helplessness. That is except for our two heroic leads. There's little left to the imagination when it comes to how the filmmakers, writers, art department, and prop folks felt about the OCP, described in one featurette as "proto-fascist." The real villains were never Boddicker's thugs, but the OCP in Italian suits.

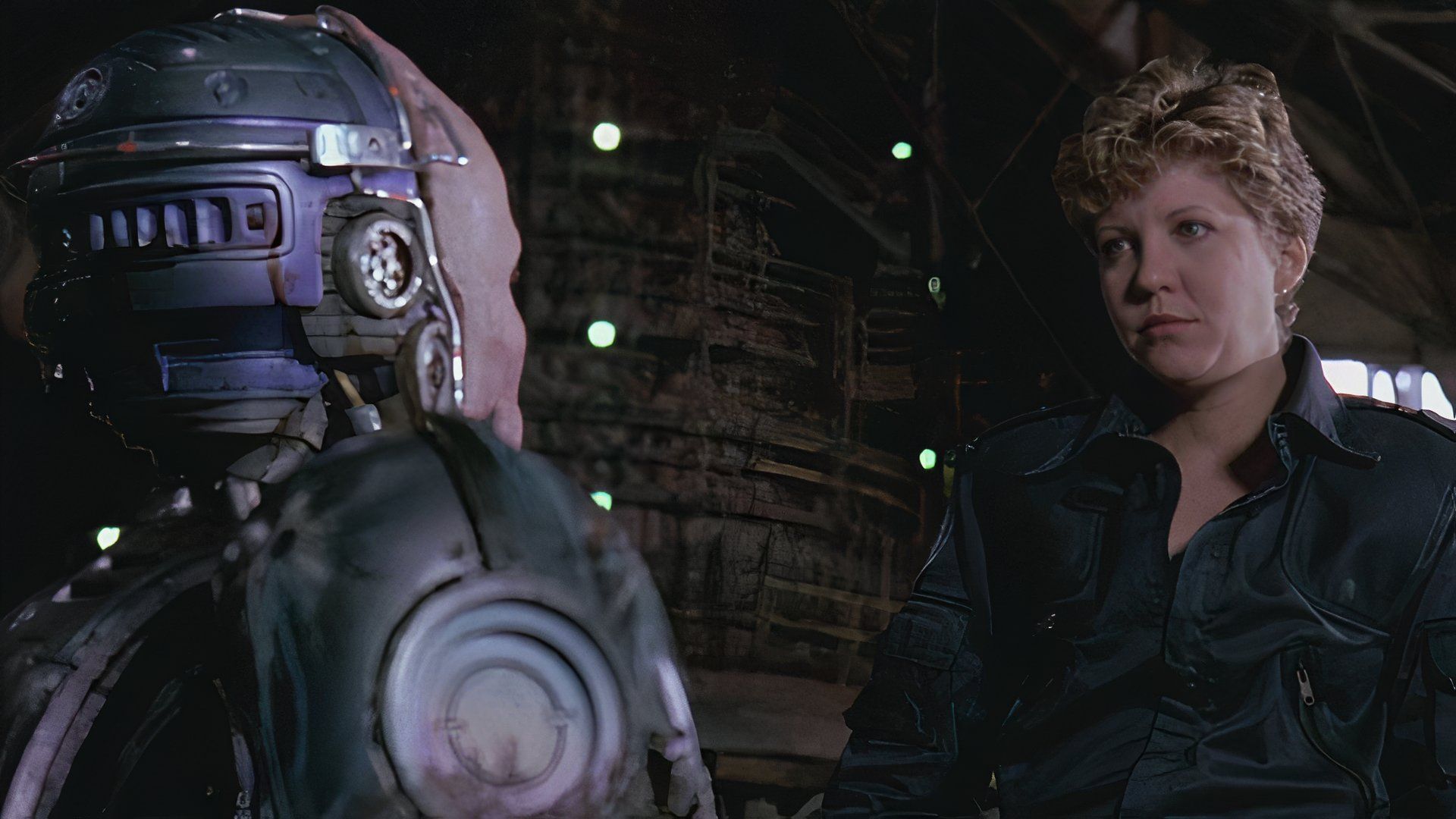

While now a product, albeit with some residual organic matter that no one bothers to consider a human being, OCP never fully comes to accept that the hunk of metal and wires is still Murphy. Nothing changed in the relationship between Murphy and Lewis after his cyborgization. His essence remains. Lewis' belief in his humanity is part of the reason he is able to come to terms with his traumatic transformation. This is elaborated on with no subtlety whatsoever in the sequel, where an OCP lackey notes that the only reason RoboCop Mk 1 worked where every other prototype failed miserably is because of the human material within the metal shell.

Murphy is "an unusual case," a "devout, Irish-Catholic family man" with "a fierce sense of duty." Thus, the second film beats us over the head with the reason why Murphy and Lewis never had the slightest romantic connection, in a blatant case of telling instead of showing.

Spoilers for a 30-year-old movie: Lewis dies in RoboCop 3. Her demise did accomplish one thing — depriving the series of ever getting the chance to explore any romantic story possibilities. Her death is melodramatic, but in the grand scheme of the three films, it does demonstrate fidelity to the character of Lewis, who would sacrifice herself for a cause, her partner, and the city, gunned down as Murphy was in the early scene in the warehouse in the first film.

If the terrible third film does do one thing right, and that number seems accurate, it is this aspect of the Lewis-Murphy dynamic that carried the whole trilogy as every other part of the production went to hell. It's appropriate the franchise expired at the very moment the duo was finally split up.