Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

Megalithic mythology – Archaeology often presents the megalithic structures of Northern Europe as enigmatic remnants of the past, but traditional interpretations of their purposes—defensive or territorial—are increasingly challenged by new research. These ancient monuments, including Stonehenge and Silbury Hill, required a level of logistical and communal organisation akin to modern engineering feats like the Channel Tunnel, suggesting sophisticated, large-scale cooperation among prehistoric societies. This blog post explores how regular trading and the use of established transportation networks likely supported such monumental projects. It argues that the labour force involved was large and part of a highly structured society, possibly operating under an early compensation system for their colossal efforts. As we delve deeper into these ancient marvels, we uncover a society that may have been as advanced and cooperative as any known civilisation, revealing a new appreciation for the capabilities and ingenuity of our ancestors – Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

Archaeologists and enthusiasts are deeply familiar with the fact that Northern Europe is scattered with megalithic structures whose origins and purposes often evade complete understanding. This reality leaves us grappling with many theories and concepts, which together form what we commonly refer to as archaeology—a field deemed a social science due to its reliance on less concrete evidence. It attempts to elucidate these enigmatic monuments to the public, although not always convincingly.

This method of discovery and exchange of information frequently falls short of adding credibility to archaeology. It often seems that these ancient monuments’ true essence and purpose are either overlooked due to a lack of knowledge or deliberately obscured, perhaps to deepen the mystery and intrigue that archaeologists have long struggled to resolve.

It is broadly recognised that constructing mammoth monuments like Stonehenge, Avebury, and the world’s largest prehistoric artificial hill, Silbury Hill, would have required millions of person-hours. This acknowledgement points to the involvement of a substantial labour force. What often goes unmentioned, however, is the intricate logistics such an undertaking entails. This level of organised labour is akin to contemporary projects like the construction of the Channel Tunnel, which demanded a consensus across an entire nation and significant economic contributions through taxes to sustain a workforce over years of construction.

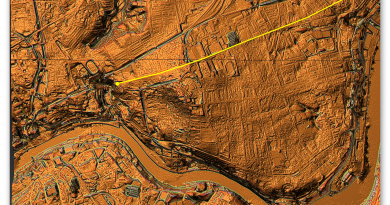

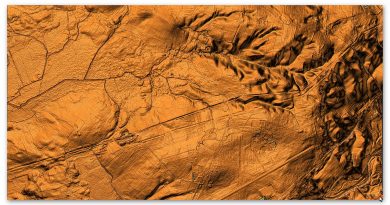

Moreover, this construction process could only have been achieved through regular trading with the region’s inhabitants. Crucially, when additional human resources were required for massive projects, the same trading routes and boats that facilitated commerce were used to transport workers to these far-off construction sites.

Another significant oversight in mainstream archaeological discourse is the discussion of the logistics behind constructing these structures. The prevailing narrative might suggest that a mere handful of individuals could erect a stone circle or a burial mound using stones that cumulatively weigh hundreds of tonnes—a feat far beyond the capacity of even several strong individuals.

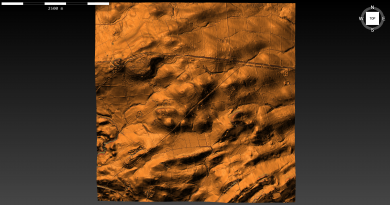

The tens of thousands of these monuments and earthworks point to an effort comparable in scale and cultural significance to our own Industrial Revolution. It must have been a collective endeavour spanned vast areas of Northern Europe, akin to a joint cooperative behaviour seen in societies united for a common good. This required extensive transportation networks to move stones over hundreds of miles, along with sophisticated communication methods.

Such a monumental task could only have been possible with a communal reward system, where individuals were compensated for their efforts—perhaps a precursor to modern monetary systems that allowed them to obtain luxury items in return for their labour. This system underscores these ancient societies’ cooperative and organised nature, which is often understated or overlooked in traditional archaeological narratives.

The uniqueness of the megalithic culture in history is profound and unparalleled until the advent of the Industrial Revolution. While the Romans may have produced more sophisticated statues and buildings, their constructions were much smaller. This suggests that, in some ways, the prehistoric culture of Northern Europe was as significant, if not more so, than the Roman Empire, especially when considering the breadth of territories they influenced.

To truly understand the scope of this ancient culture, we must step back and apply our analytical skills and logic. This involves identifying who these people were, where they went in our historical timeline and the true extent of their cultural influence. Only by doing so can we begin to uncover the natural history of these lands, rather than settling for half-baked ideas that gloss over the transformative impact and scale of this culture that still resonates five thousand years after they vanished.

By questioning the simplistic explanations currently accepted, we might discover that these ancient builders were part of a highly sophisticated society, operating with an efficiency and scale of cooperation that rivals even the most advanced civilisations of classical antiquity.