22 May 2024

MUSUBI KILN Chado Series:

A Walk through a Samurai's Path of Tea

Every tea experience holds its own uniqueness, a moment to be treasured and embraced. Yet, venturing into the world of chado, the way of tea, can feel like stepping into the unknown with its long historical background and cultural significance.

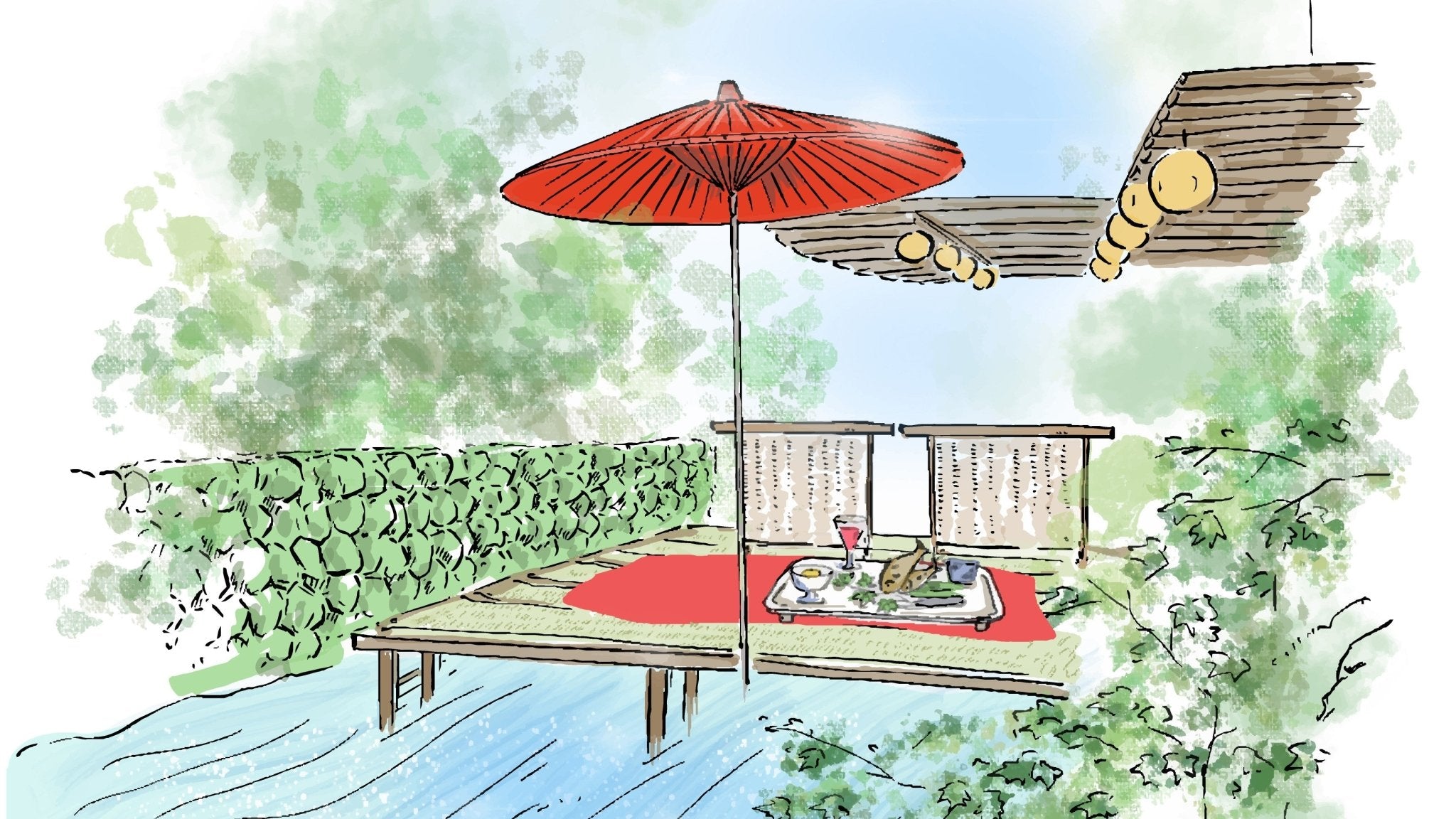

At Komaba Warakuan, however, chado comes alive in a warm and inviting atmosphere. Here, newcomers and connoisseurs alike are welcomed to indulge in the pleasures of matcha and discover the art of the Japanese tea ceremony.

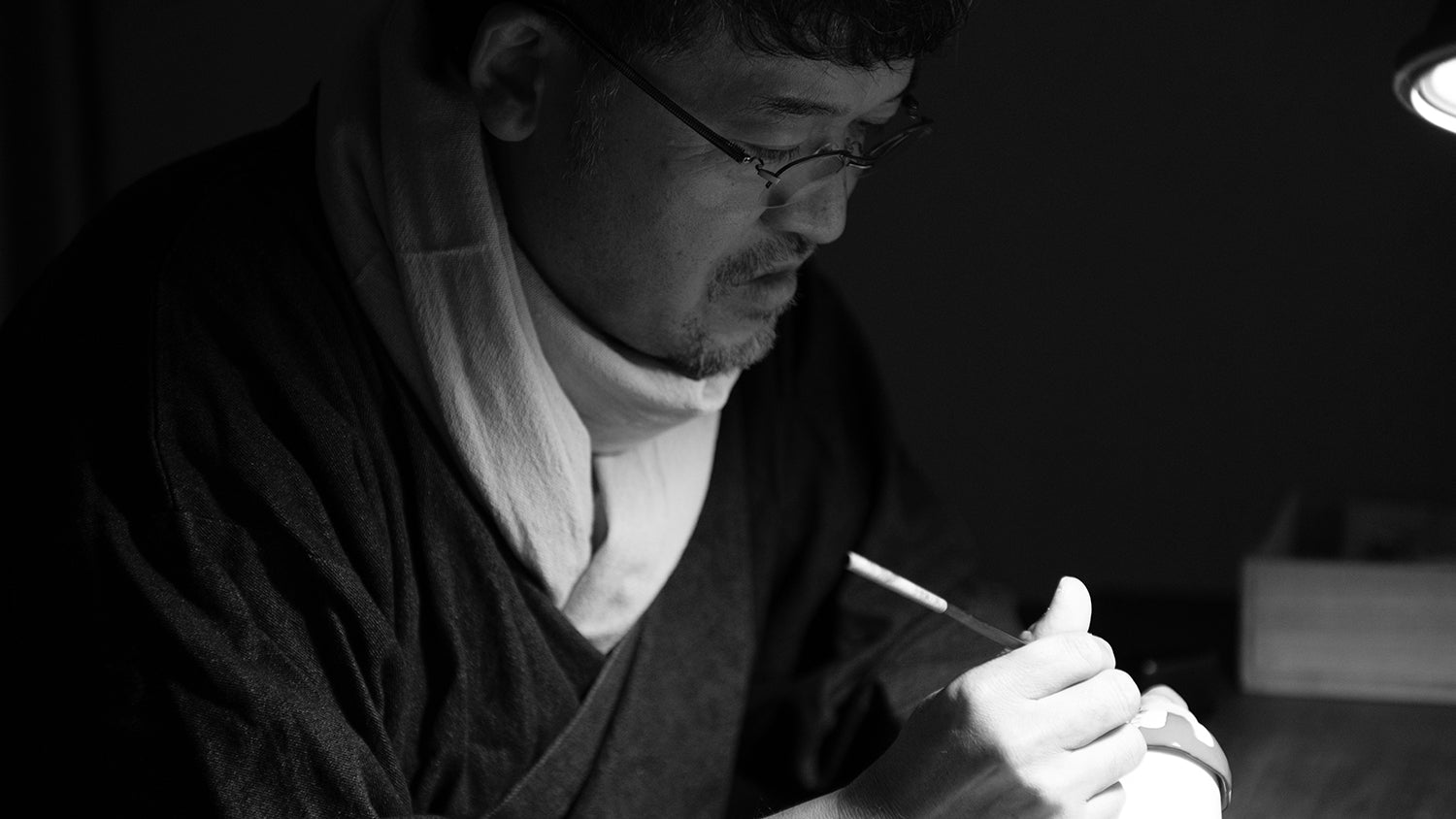

Join us as Team Musubi ventures into this oasis of tranquility, where tea master Maeda Sourei extends a warm welcome and guides guests through time-honored practices and etiquette with grace and hospitality.

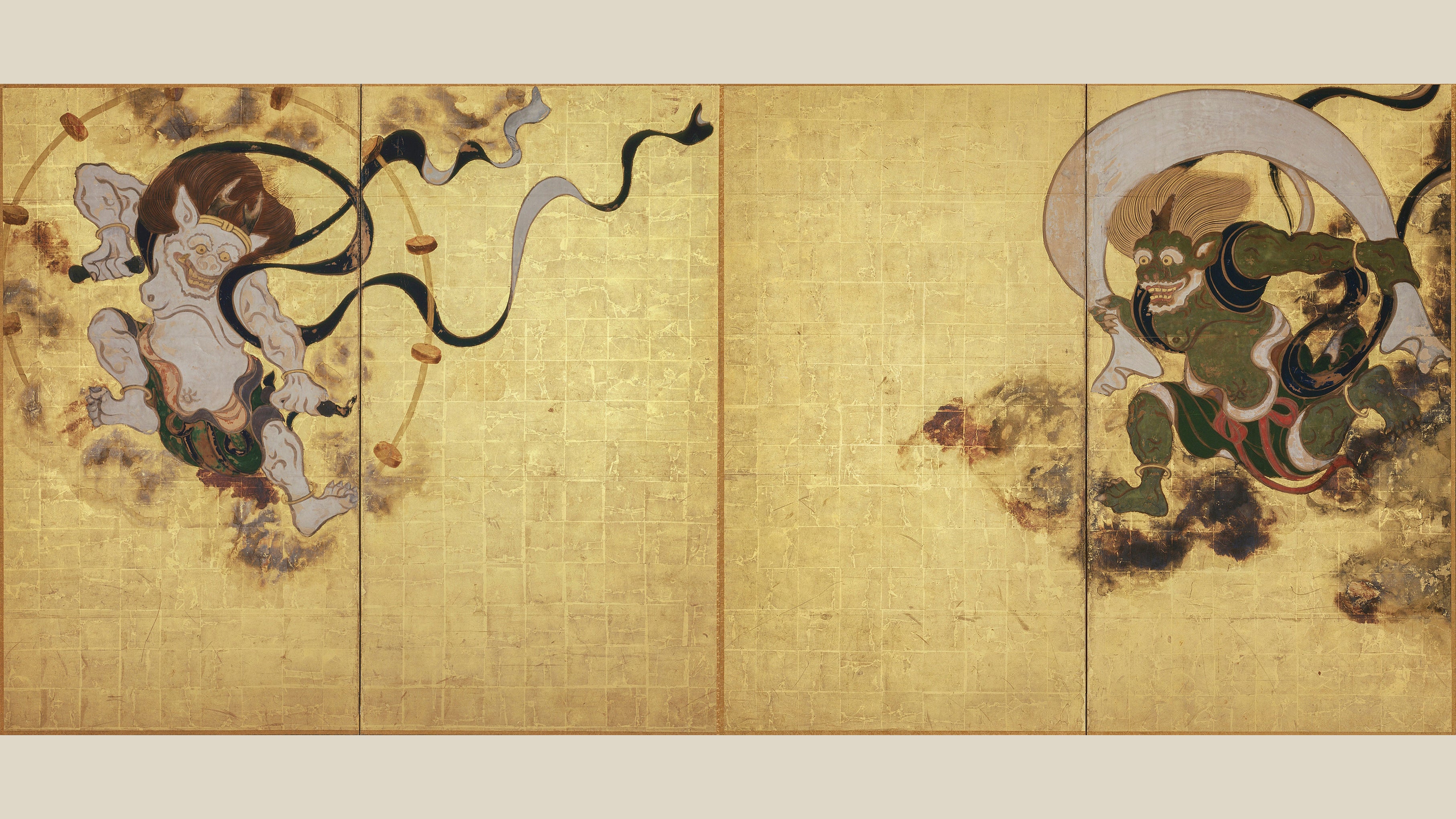

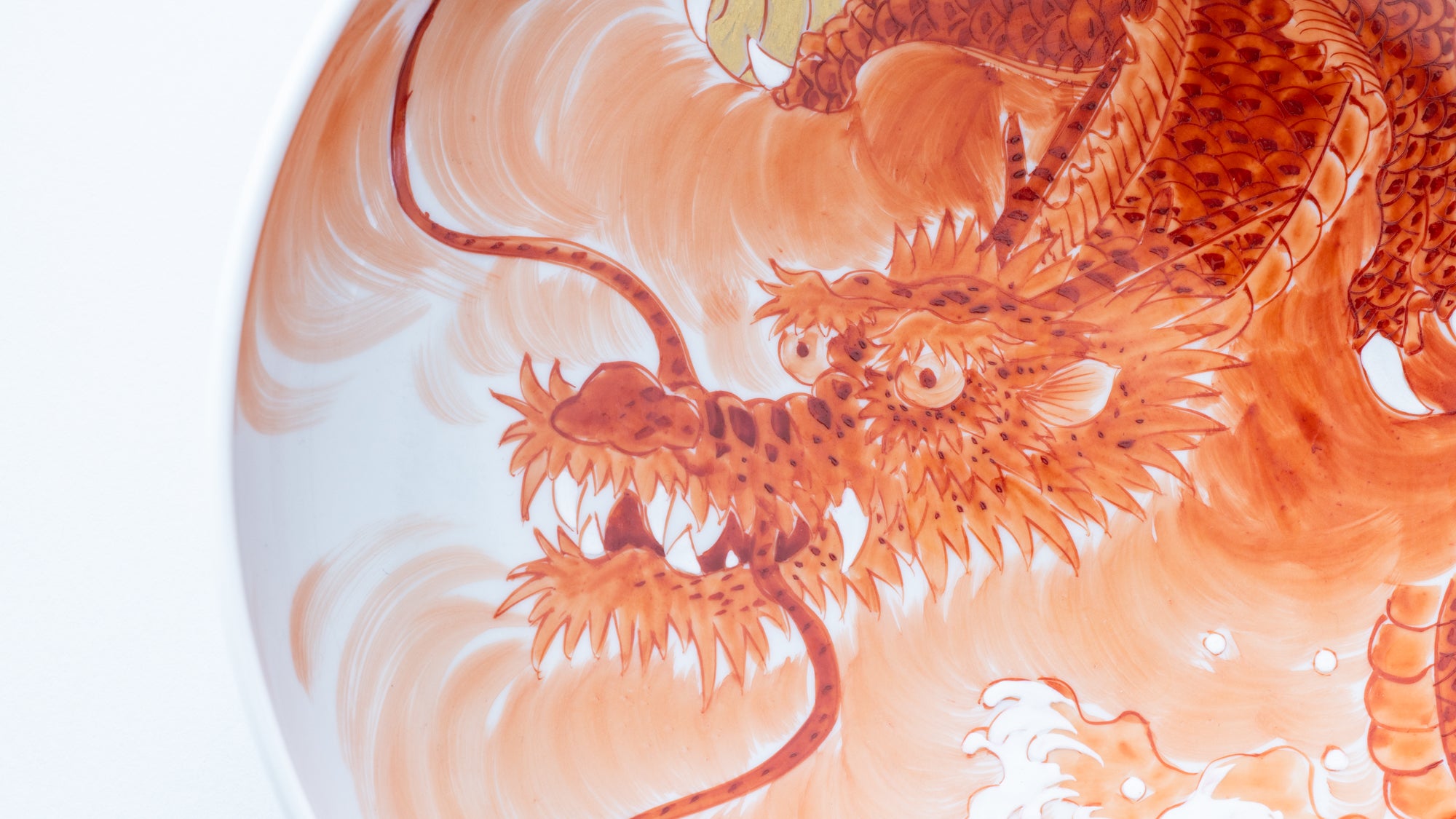

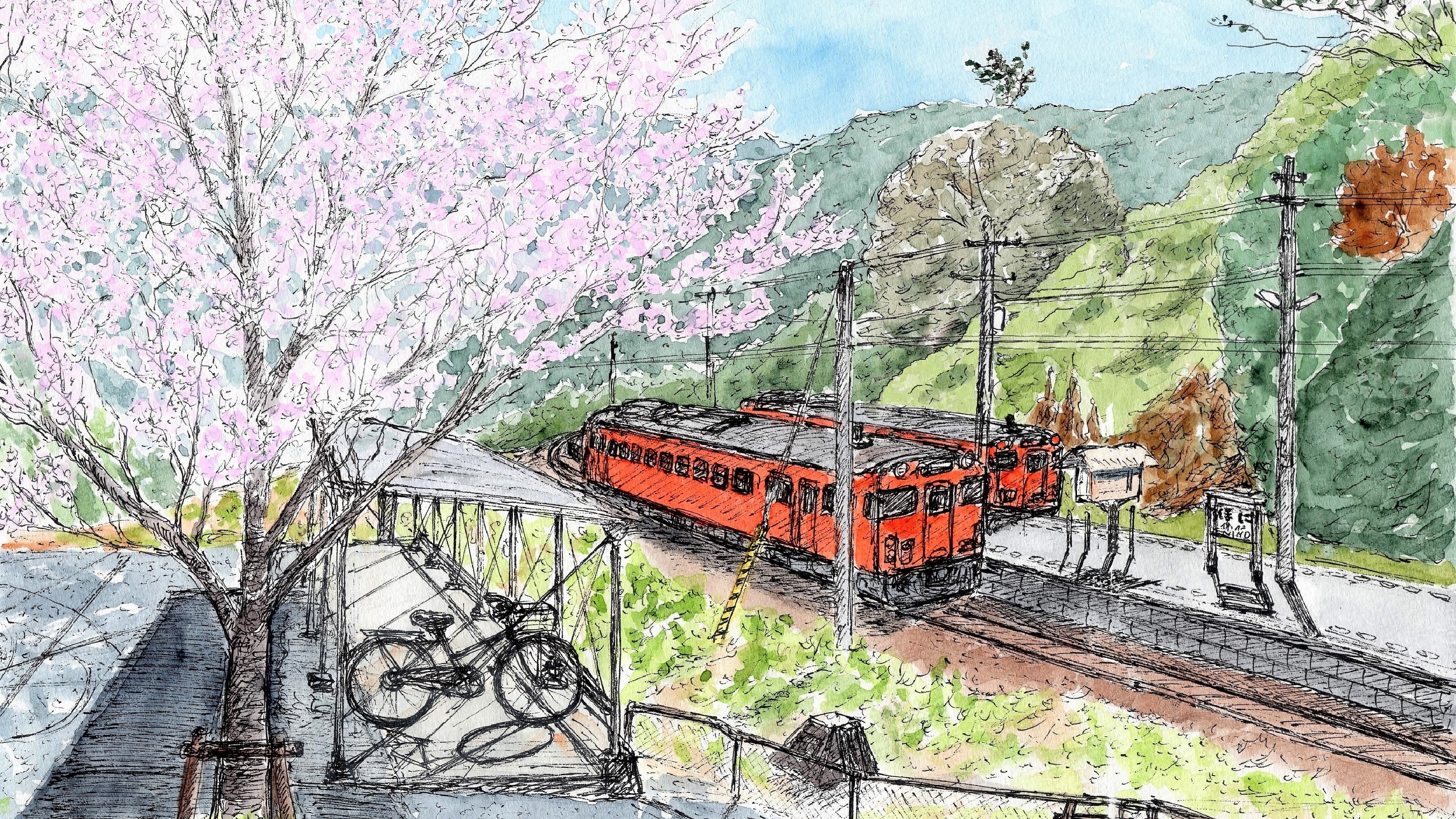

Located just two stations away from the bustling Shibuya station, the tea room of Komaba Warakuan awaits in a serene residential area. At Komaba Warakuan, guests have the opportunity to delight in chado of the Kobori Enshu School. Its origin traces back to a samurai, feudal lord Kobori Enshu (1579 CE–1647 CE). Serving under the Tokugawa shogunate as an architectural advisor and tea ceremony instructor, Kobori Enshu forged his own unique style of chado, blending the aesthetics of wabi-sabi with aristocratic elegance.

Upon arrival, we were warmly greeted by Maeda-sensei, clad in the traditional attire of a kimono and hakama.

At the main entrance, we removed our shoes, replacing them with handwoven straw sandals, zori. Passing through a small gate, we followed a paved path to the tea room. We washed our hands and rinsed our mouths at the tsukubai, a stone basin filled with fresh water, before entering.

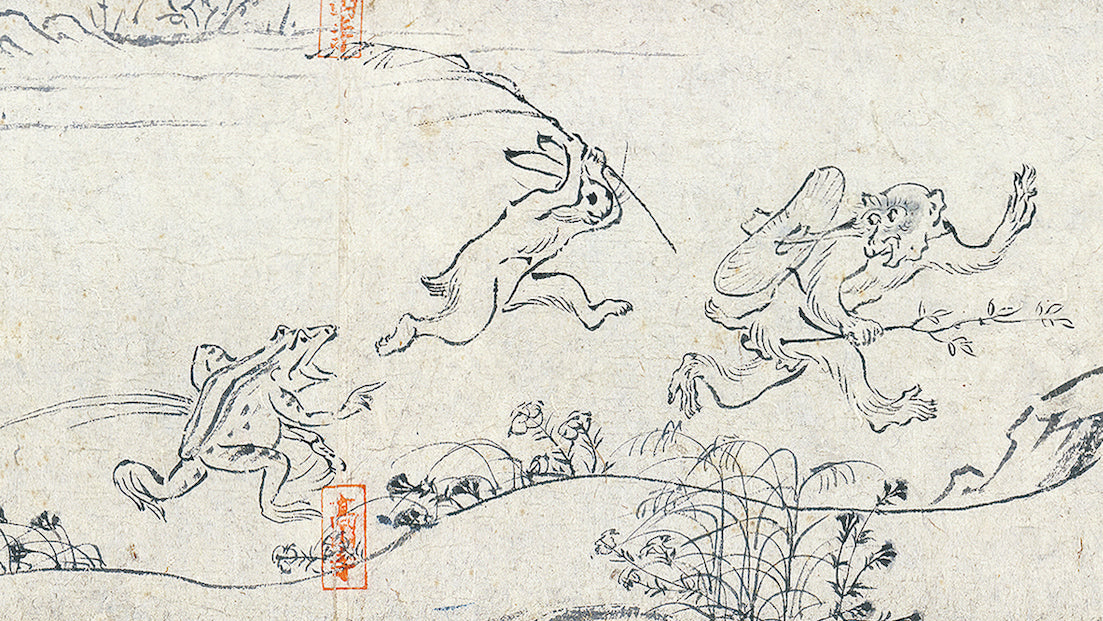

At the entrance of the tea room, we took off our zori sandals, overlapped them, and set them aside. Upon entering the tea room, we were invited to inspect the walls and ceiling, reminiscent of the old tradition where samurai warriors ensured their safety, as weapons were not allowed inside a tea room.

First, we admired the hanging scroll and flowers at the toko, or alcove. Delicate fringed irises adorned a Bizen ware vase hanging from the wall. Just as we prepared to kneel on the tatami mat to receive our tea, Maeda-sensei provided zabuton cushions, a thoughtful touch for novice participants. Additionally, stools are available for those who prefer them.

Before drinking the tea, wagashi is served to tantalize the palate for the taste of matcha. The Japanese confection for our chado experience was a mochi with a sweet bean sakura filling, perfectly reflecting the charm of the sakura season.

As a comforting silence filled the tea room, Maeda-sensei began to prepare the tea. April is the only month of the year where a tsuri-gama, a hanging kettle, is used for heating the water. Maeda-sensei adjusted the temperature of the hot water by slowly adding a scoop of water to the pot.

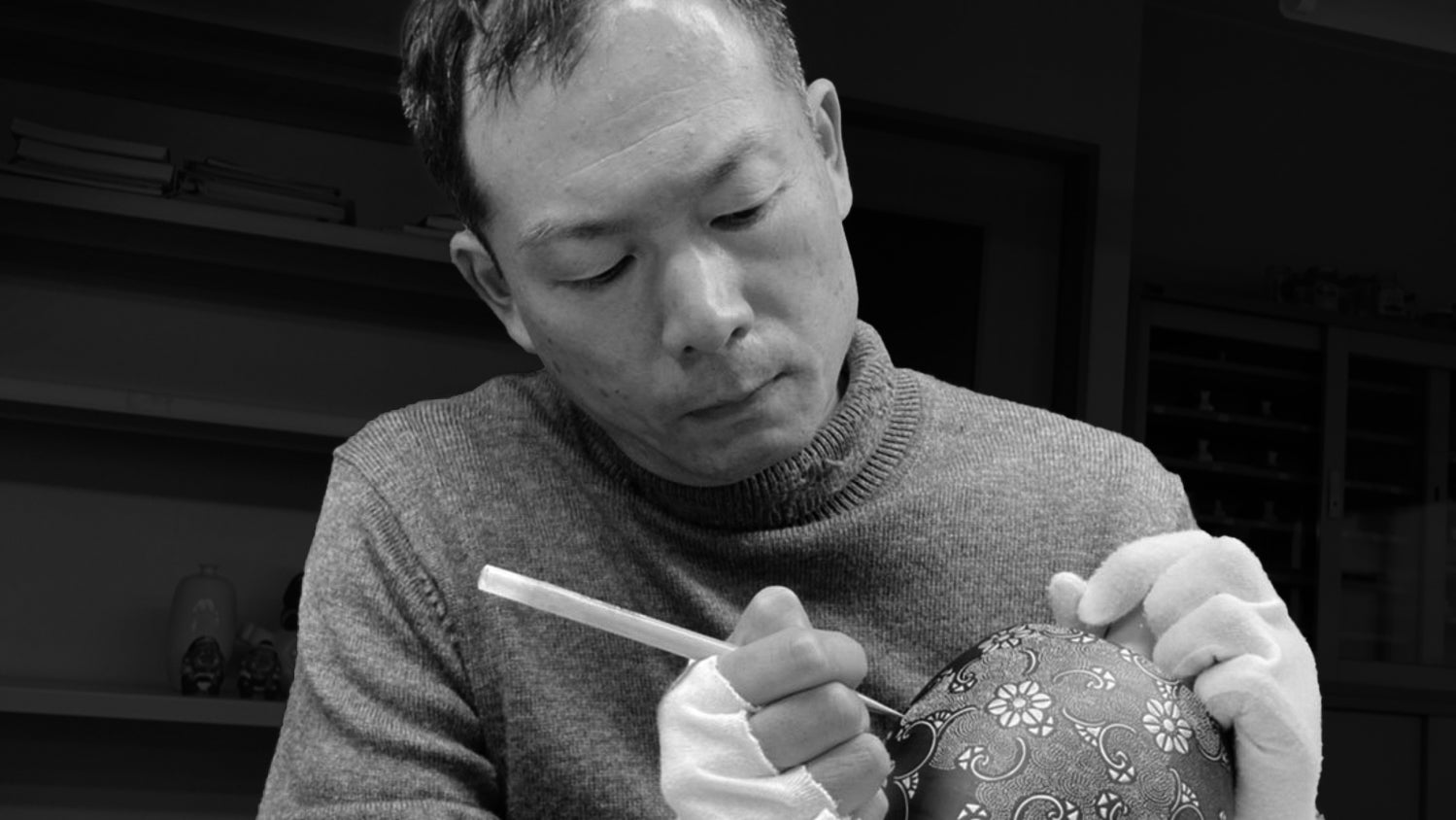

Placing the selected matcha bowl for today's tea serving, Maeda-sensei measured two scoops of matcha from the natsume, matcha container, and quietly poured hot water with the bamboo ladle. The sound of the gentle splash of hot water, and of the chasen, matcha whisk, gently swishing back and forth was soothing as much as it was enticing.

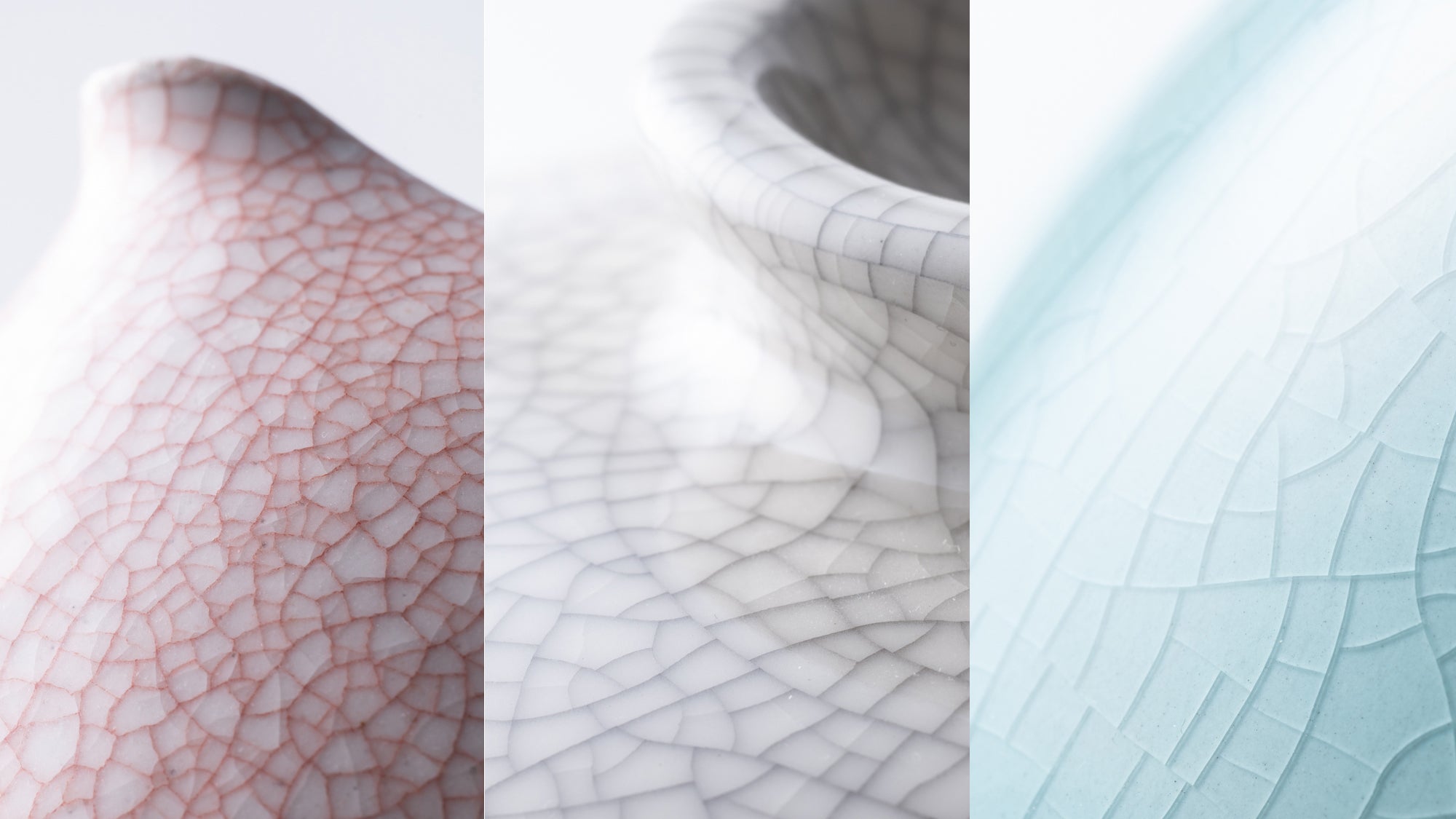

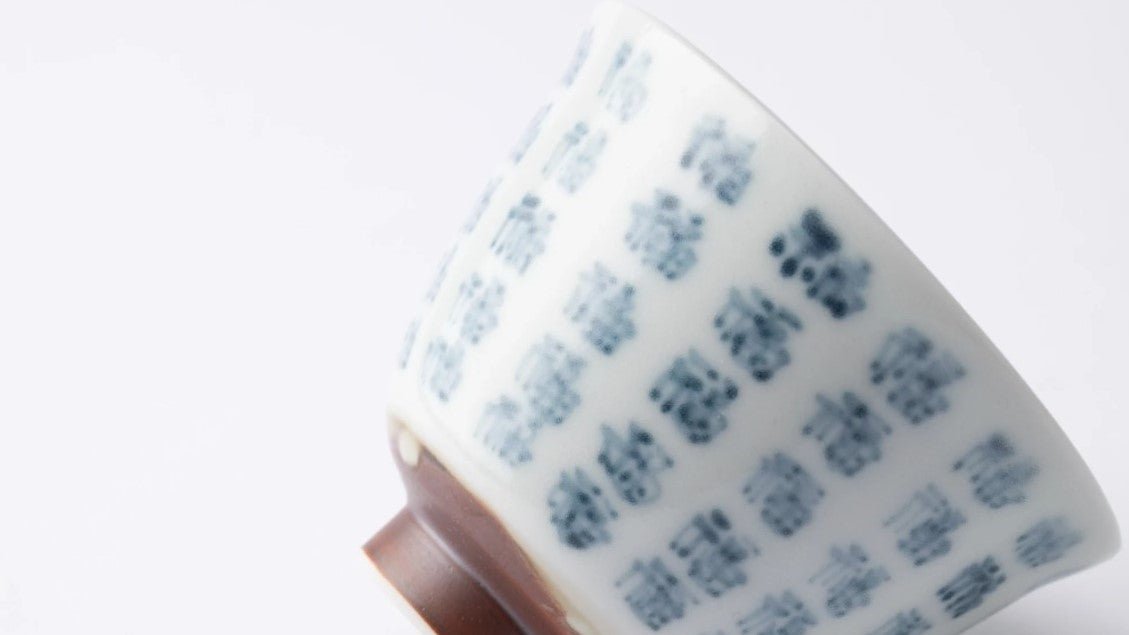

As the warm bowl of matcha was placed in front of me, I politely said, "Osaki ni (I will humbly drink before you)" to my colleague on my left before savoring my bowl of tea. Both refreshing and rich, each sip offered a slightly different flavor with its smooth, silky froth. A subtle slurp signals the host you are finished. I wiped the rim clean with two fingers before holding the bowl in both hands, elbows resting on both knees to admire its craftsmanship.

Once my colleague finished her tea, Maeda-sensei carefully cleaned each utensil with hot water from the hanging kettle. After he was finished, he presented us with the natsume and chashaku. The natsume was a breathtaking lacquerware piece adorned with intricate maki-e designs. And the chashaku, with its sharper angle compared to the one we use at our office, was a pleasant discovery indeed.

And thus, our chado experience quietly drew to a close. We departed through the same entrance, slipping on our zori sandals. It's customary etiquette to set the zori for the next person once you've put on your own.

After our chado experience, Maeda-sensei shared his hopes of creating an environment where guests can savor delicious tea while feeling the warmth of his hospitality, nurturing a sense of unity between host and guest.

Before the pandemic, the majority of his guests were visitors from abroad. Although not a native English speaker, Maeda-sensei is well-prepared and experienced in warmly welcoming anyone who wishes to immerse themselves in the world of chado. Detailed instructions will be kindly provided during your visit. Reservations can easily be made on Komaba Warakuan's website, and it's advisable to secure your preferred date by booking two to three days in advance.

If you’re still up for a stroll after visiting Komaba Warakuan, consider heading over to the Japan Folk Crafts Museum (Nihon Mingeikan) on the other side of the nearest station, Komaba-Todaimae. It's another cultural treasure trove waiting to be explored.