Abstract

Editing services within academic health centers are uncommon, and few studies have reported on their impact. In this article, we describe our medical writing center’s editing service for faculty and trainees at a pediatric teaching hospital and associated outcomes of scholarly products (e.g., manuscripts and grants) over an 8-year period. Data for manuscripts and grant proposals edited by the writing center from 2015 through 2022 were collected electronically from our service request database. Outcome data on publications and grant proposals were regularly collected up to 12 months post-submission. Users were also asked if the writing center edits were helpful, improved readability, and if they planned to use the service in the future. From 2015 through 2022, the writing center received 697 requests, 88.4% to edit a document. Of the documents edited, 81.3% of manuscripts and 44.4% of grant proposals were successfully published or funded. When rating their experience, 97.8% of respondents rated the edits “helpful,” 96.7% indicated the edits “improved readability,” and 99.3% stated they planned to use the writing center in the future. Our results showed steady use of the writing center and high satisfaction with services. A writing center can be an effective tool to support psychology faculty development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Peer-reviewed publications and grants are critical for the dissemination of knowledge in academic medicine and psychology. Publications and grants also provide important evidence of scholarly activity for promotion and career advancement. Yet to produce effective manuscripts and grant proposals, faculty and trainees in academic health centers (AHCs) often need guidance, particularly if they lack experience with these types of professional writing. Historically, medical schools in the U.S. have rarely taught skills in writing manuscripts and grant proposals, despite considering them important for academic physicians and trainees to learn (Yanoff & Burg, 1988). In the field of clinical psychology, although research writing is common and academic writing skills are emphasized, trainees and early career psychologists have identified grant writing as one topic in which they need additional training (Yarrington et al., 2023). Psychology PhD and PsyD programs also tend to differ regarding academic writing instruction, where PhD programs generally emphasize the development of research skills and generation of new scientific knowledge, while PsyD programs generally emphasize the application of knowledge to clinical practice (Michalski & Fowler, 2016).

Even with experience in writing manuscripts and grant proposals, junior physician and psychology faculty and trainees in AHCs can find the process of preparing and submitting scholarly work to be daunting. As faculty in psychology and medicine advance in their careers, finding the time to write and to mentor trainees in their writing can be challenging due to increasing clinical, teaching, and research demands (Eastwood et al., 2000; Grzybowski et al., 2003; Lim et al., 2019). Because of these pressures and challenges, there is great need to support faculty and trainees in AHCs in producing high-quality manuscripts and grant proposals.

One way AHCs can support faculty and trainees with manuscript and grant writing is through an in-house editing service. While editing can vary from light copyediting to substantive review of content, the primary function of editing is to ensure that documents are clear, readable, and appropriate for the target audience. In contrast to editors who work for publishers, editors in AHCs are “authors’ editors,” who refine authors’ documents before submission to academic journals or other venues (Matarese, 2016). Some editors at AHCs may also offer one-on-one writing consultations (Derish et al., 2007; Dornhoffer, 2012; Lim et al., 2019) or work with authors or research teams in the early stages of a project’s development (Dornhoffer, 2012). The individualized support offered by an editing service can be particularly beneficial to trainees by helping them to develop skills that their mentors may lack the time, knowledge, or inclination to teach. Editors can also help writers for whom English is an additional language (EAL) to navigate the conventions of academic writing in English (Cameron et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2019) and interpret and respond to reviewers’ comments (Breugelmans & Barron, 2008).

Editors working within an in-house editing service can also support trainees and faculty more broadly by providing workshops, training sessions, and writing resources. Numerous studies have shown effectiveness of various educational interventions to increase scholarly productivity in AHCs, such as writing workshops (Cameron et al., 2009), peer-mentoring programs (Pololi et al., 2004), writing groups (Grzybowski et al., 2003), and writing retreats (Stanley et al., 2017). Editors can lead these workshops and training sessions and build from them by encouraging participants to use editing and consulting services or establishing ongoing, structured editor-advisor relationships with participants (Cameron et al., 2009; Matarese, 2016; Stefani, 2014). Additionally, editors can develop educational resources in a variety of formats (e.g., handouts, newsletters, how-to guides, templates, videos), collate and share external information on topics related to writing and publishing, and create repositories of helpful documents such as examples of successfully funded grant proposals. Because editors are located onsite within the AHC, they can also direct faculty and trainees to other institutional resources that might be helpful to their research or professional development.

Despite reports of high satisfaction generally with in-house editing services (Conners et al., 2023; Derish et al., 2007; Dornhoffer, 2012; Lim et al., 2019), challenges exist to providing editorial support of this kind for faculty. As with any institutional resource, costs are associated with administrating the service and hiring personnel. Editors performing this work at AHCs must have a specialized set of skills, including skills in language editing and knowledge of writing conventions in academic medicine and the social sciences. Many examples exist of editors working in research centers, both in the U.S. and internationally (Matarese, 2016). However, most commonly, a single editor is hired by an individual academic division or department to support research efforts of its faculty and trainees. Less common in AHCs are editing teams who edit manuscripts and grant proposals for faculty and trainees across disciplines within an institution. Further, reports describing these editing services and their impact on publication and funding outcomes are scarce in the literature. In this article, we describe the services of our editing team at a medical writing center, which provides highly skilled editing support at no cost to all physician and psychology faculty and trainees at an independent pediatric teaching hospital. We report on methods, availability to faculty and trainees, and associated outcomes of their scholarly products, principally manuscripts and grants, over an 8-year period.

Methods

The Medical Writing Center (MWC) is located within a major pediatric teaching hospital in the Midwest. The hospital has over 800 faculty across 54 specialties, 84% of whom are physician and psychology faculty and 16% are PhD research faculty. The hospital also has over 40 fellowship programs and three residency programs that encompass more than 200 active trainees. The MWC is currently staffed by a part-time director and full-time senior editor. The services of the MWC are fully funded by the hospital and free to any faculty, trainee, or staff member to use.

When we launched the writing center as part of the institution-wide Office of Faculty Development in 2015, our immediate aim was to raise the quality of writing in academic products to increase the likelihood of publication or funding success. In addition, as writing center professionals, our secondary aim was to provide training to help faculty and trainees become better writers. As Stephen North (1984) described in a seminal essay in writing center scholarship, the function of writing centers “is to produce better writers, not better writing” (p. 438). Thus, in addition to editing services, the MWC provides education, training, and consultations to help faculty and trainees develop academic writing skills.

Writing workshops, open to the entire hospital community, are provided once or twice a year through the Office of Faculty Development curriculum. Topics of past workshops have included basics of successful scientific writing and steps for publishing a successful academic paper. Targeted writing workshops are offered by request to individual divisions and departments and provide tailored writing instruction to groups of 15 to 20 participants, who are encouraged to submit a work-in-progress and several sample articles for the larger group to analyze, discuss, and revise. Manuscript preparation groups are also offered by request to small groups of four to six participants who are working in a similar field of research, such as neonatology or developmental-behavioral pediatrics, or on similar types of projects, such as quality improvement. Finally, one-on-one consultations are also available to authors to discuss scholarly projects at any stage of development or to address specific writing concerns.

The MWC’s Editing Service

Faculty and trainees request a range of assistance from the MWC from copyediting and proofreading to more extensive editing and guidance with the writing process itself, such as strategies for overcoming writer’s block, organizing sections of a manuscript or grant proposal, or selecting a target journal. Authors typically request editing for manuscripts and grant proposals, but they also may submit other professional documents, including personal statements, book chapters, and newsletter articles. Editing services are requested through an electronic portal on the hospital’s intranet hosted by REDCap electronic data capture tools, a secure web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research and operational initiatives (Harris et al., 2009, 2019).

Because copyediting is most effective after all major revisions have been made, the director first reviews the document to ensure it is complete and at a near-final stage. If an author submits a rough draft, the director will suggest that the author submit the document for editing closer to the time of journal or grant submission or, alternatively, request a one-on-one consultation. If the document appears to be ready for copyediting, the request goes into the editing queue, and within one business day the author receives a timeline for services. The quoted turnaround time for manuscripts is within five business days of the request, and within seven business days of the request for grant proposals, although the majority of requests are returned within fewer business days. Major institutional grants and projects are assigned priority for editing. All documents are edited by both the director and senior editor, with final edits and comments reviewed by the director before being returned to authors (Fig. 1).

Editing typically consists of light copyediting and careful proofreading to improve readability and correct errors in grammar or usage. Editors query authors about substantive concerns, such as organization, coherence, and logic. Editors carefully review instructions from the target journal or funder to ensure the document conforms with style and formatting requirements; however, editors do not make formatting changes. During the editing process, the editors often refer authors to other institutional resources, such as library services for help conducting literature reviews, using reference software, and avoiding predatory journals. The editors also regularly direct authors to a resources page on the hospital’s intranet they created in collaboration with the Office of Faculty Development director and experienced research mentors at the hospital. These resources include 40 how-to guides, videos, and templates grouped into five categories: (1) abstracts, presentations, and lectures, (2) manuscripts, (3) grants, (4) peer reviews, and (5) personal statements, cover letters, and recommendation letters.

MWC Administration and Editing Expertise

The MWC has maintained its original staff since its founding in 2015. Both the director and senior editor have professional academic experience in teaching English composition and rhetoric and are also experienced specifically in scientific and medical editing. The director has a PhD in English-language and literature, as well as extensive experience teaching bioethics, narrative ethics, and writing to students, trainees, and faculty. She oversees the general administration of the center, schedules and organizes editing services, edits and proofs all documents, teaches writing workshops and manuscript preparation group sessions, and organizes and oversees consultation and editing services. The senior editor has a master’s degree in English-language and literature and is certified by the Board of Editors in the Life Sciences. She manages daily administration of the MWC, conducts writing consultations, and edits and proofs documents.

Study Design and Objective

This study was deemed to be not human subjects research and therefore exempt from approval by the hospital’s institutional review board. We reviewed retrospective data, including outcomes and satisfaction data, from all users of the writing center from 2015 through 2022. Our objective was to determine whether a medical writing center in an academic teaching hospital is an effective tool for supporting faculty and trainees in producing publishable manuscripts and funded grant proposals.

Data Analysis

Study data were extracted from the electronic service request database. We limited analyses to requests for manuscripts and grant proposals. We analyzed frequencies and descriptive statistics for service requests, outcomes, and satisfaction data over 8 years (2015–2022) using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York). We collected outcomes data for manuscripts and grant proposals regularly via follow-up emails, surveys, and searches of PubMed and National Institutes of Health RePORTER databases up to 12 months post-submission. On post-submission surveys, we asked users whether the writing center edits were helpful, whether they improved readability, and whether users planned to use the service in the future.

Results

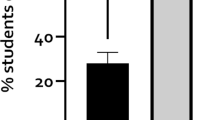

From 2015 through 2022, the MWC received 697 requests, 88.4% (n = 616) to edit a document, 7.7% (n = 54) to receive consultation on a document, and 3.9% (n = 27) to schedule a writing workshop (Table 1). Over the eight study years, the MWC received an average of 77 editing requests per year from across the organization, a number that steadily increased from a low of 36 in 2015 to a high of 112 in 2020. Of the documents submitted for editing, 63.4% (n = 391/616) were manuscripts, 16.1% (n = 99/616) were personal statements, 8.8% (n = 54/616) were grant proposals, and 11.6% (n = 72/616) were other document types (e.g., book chapters, newsletter pieces). A small subset of editing requests (11.0%; n = 68/616) were for documents submitted more than once for review by the MWC. Most editing requests were submitted by users who were female (59.1%), White (57.2%), and faculty (72.8%) (Table 2). The majority of faculty requesters were physician faculty (56.7%), held associate professor rank (31.7%), and had medical degrees (57.0%). Of the 616 documents edited by the MWC, 81.3% (n = 318/391) of manuscripts and 44.4% (n = 24/54) of grant proposals were successfully published or funded within 12 months of submission to the MWC (Table 3). Over 8 years, the rates of successful publication of manuscripts edited by the MWC varied from a low of 68.0% in 2015 to a high of 88.1% in 2018, while rates of successful funding for grant proposals edited by the MWC varied from a low of 33.3% in 2017 and 2018 to a high of 66.7% in 2019 and 2020. Thirty-nine percent (n = 273/697) of users responded to post-editing surveys conducted by the MWC. When rating their experience, 97.8% of survey respondents rated the edits “helpful,” 96.7% indicated the edits “improved readability,” and 99.3% stated they planned to use the writing center in the future (Fig. 2). These responses remained uniformly high across nearly all 8 years in the study, particularly as the user feedback surveys became a routine part of the editing process in 2019–2022.

Discussion

Our results indicate that an editing service within an AHC is an effective tool in supporting faculty and trainees in producing publishable manuscripts and funded grant proposals. Our outcome and satisfaction data demonstrate that faculty and trainees regularly use our editing services and find the edits and comments helpful for improving their documents. Resubmission rates show that authors also submit drafts for multiple rounds of editing, suggesting that authors value working with editors through the editing process.

Our study adds to the limited literature on in-house editing services. Several longstanding academic editorial departments offering these services exist, notably Mayo Clinic’s Section of Scientific Publications, which traces its origins back to 1907 (Pike, 2005). However, only a few studies of editing services similar to ours have provided empirical data on the value of editing services to academic institutions. Lim et al. (2019) described their editing service providing both in-house editing and referral to external editing service for faculty writing English-language manuscripts at the largest AHC in Korea. The authors reported increased research productivity after implementing the service and high satisfaction, particularly for editing performed in-house. Similarly, Breugelmans and Barron (2008) showed a steady increase in publication rates over a 17-year period following implementation of their large editing service, which provides English-language manuscript editing for authors at Tokyo Medical University. Several articles describing editing services in AHCs in the U.S. have also reported on operational metrics (Conners et al., 2023; Dornhoffer, 2012; Lang, 1997). For example, Lang (1997) provides detailed information on metrics such as number and type of documents edited, turnaround time, user satisfaction, and estimated percentage of the institution’s publication output edited by the editing service. However, to our knowledge, no authors have yet reported on individual outcomes of manuscripts and grant proposals submitted to editing services, as in our study.

Similar to other authors, we have found important benefits of our editing service for junior faculty, trainees, and EAL writers. Anecdotally, faculty mentors frequently send emails of appreciation to the MWC for providing a valuable resource for junior faculty and trainees. We often complement the role of mentors by providing guidance on manuscript and grant writing as well as by performing the time-intensive work of sentence-level editing. Additionally, residency and fellowship applicants interviewing at our hospital have commented on the distinctiveness and appeal of having an editing service available to trainees. For EAL authors, our editing service can be helpful for eliminating language errors and smoothing syntax. However, this benefit is not unique to EAL authors, as many native English speakers struggle as much if not more with English grammar and expression. Like other editing services, we have found that we can provide guidance in the conventions and nuances of English-language academic writing (Breugelmans & Barron, 2008; Cameron et al., 2009), which can differ considerably from those of other countries.

Our data show that the majority of MWC users are female, physician faculty, which reflects the composition of our faculty demographics. Associate professors also have the highest use rate of MWC services, which could be because we only had access to data on current academic rank and not rank at the time of MWC request submission. It is possible that users of the MWC may have been able to produce sufficient scholarship to support promotion to the next academic rank. Additionally, our data suggest that psychology faculty and faculty who identify as Black, Hispanic, and multiracial use MWC services less often than physician or research faculty or faculty who identify as White or Asian, respectively. Since faculty who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM) often experience scholarship delay in academic medicine (Oh et al., 2021), intentional efforts to help connect URiM and psychology faculty to MWC services could increase future use and support scholarship productivity for career advancement.

Our MWC model has several notable strengths. First, published articles of in-house editing programs indicate that most programs charge fees for some or all services (Breugelmans & Barron, 2008; Dornhoffer, 2012; Lim et al., 2019). One of our model’s greatest strengths is that our services are available to all physician, psychology, and research faculty and trainees across the institution at no cost. Second, we have complete outcomes data for the 8 years of this study due to our follow-up processes, including sending automatic outcome surveys at regular intervals, emailing authors directly, and searching the PubMed and National Institutes of Health RePORTER databases to learn the status of manuscripts or grant proposals that we have edited. Finally, we are an integral part of our institution’s Office of Faculty Development, which actively promotes the MWC as one of multiple resources available to support faculty along their career journey in academic medicine.

Our study also has several limitations to note. First, we are limited in the conclusions that we can draw about the impact of editing services on publication and funding outcomes. A manuscript may be rejected or grant proposal unfunded for multiple reasons that have nothing to do with the quality of the writing. We also cannot be sure that the version of the document ultimately submitted to the journal or funder was the same one we edited, as authors may continue to make changes before submission. Second, we do not have data to assess whether those who use our services have a greater likelihood of publication and funding success than those who do not. Comparing the publication rates of users and non-users of the editing service, as other editors have done (Palmer & Mallia, 2015), could be worthwhile. A third limitation is that while we have expertise in scientific editing, we are not scientists or experts in authors’ specific fields, so we cannot provide substantive editing of content. However, our layperson’s perspective may be helpful as journal articles and grant proposals are increasingly being read by multidisciplinary audiences. Fourth, our data to further assess the impact of editing services on important user subgroups, such as psychology or URiM faculty, is limited, which restricts our ability to draw broader conclusions about the usefulness of these services for all faculty members. Finally, the several hundred users who responded to follow-up surveys of MWC editing requests represent only approximately 40% of users’ perspectives. It is not possible to know whether feedback might not have been as overwhelmingly strong if more users had shared their perspectives.

Our study shows the importance of providing writing support in the development of scholarly products, namely manuscripts and grant proposals, for faculty and trainees within AHCs. It also demonstrates the usefulness of this tool for the career development of faculty, including physician, psychology, and research faculty. Possible future directions for the MWC include evaluating the impact of our workshops and training sessions on writing self-efficacy. Although we have previously collected some data on participant satisfaction with these sessions, we have not used a validated instrument to measure writing development among participants. Another direction is expanding our staff with expertise in specific areas, such as reviewing CVs or presentations for conferences. Over the years, we have provided an important service of reviewing faculty personal statements for promotion, which has raised the quality and completeness of these critically important documents for faculty members’ career advancement. Expanding into similar areas, such as reviewing CVs, would add a much-needed service for faculty.

Our writing center could also benefit from the unique expertise of clinical or research psychologists, who could design resources and coaching materials specific to psychologists, as well as provide input into one-on-one consultations, where we often address writing concerns that have a psychological component, such as overcoming writer’s block. Another area of future growth involves data reporting and analytics. We are currently working to develop a metrics dashboard for our satisfaction and outcomes data, which will help us better measure the impact of our services, identify areas for improvement, and continue to build upon our successes.

Data Availability

All relevant data are available within the paper.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Breugelmans, R., & Barron, J. P. (2008). The role of in-house medical communications centers in medical institutions in nonnative English-speaking countries. Chest, 134(4), 883–885. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-1068

Cameron, C., Deming, S. P., Notzon, B., Cantor, S. B., Broglio, K. R., & Pagel, W. (2009). Scientific writing training for academic physicians of diverse language backgrounds. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 84(4), 505–510. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819a7e6d

Conners, D. E., Brooks, J. L., Epstein, J. G., & Gollnick, S. O. (2023). Ten lessons learned from starting a new scientific editing program at a comprehensive cancer center. Science Editor, 46, 86–89. https://doi.org/10.36591/se-d-4603-01

Derish, P. A., Maa, J., Ascher, N. L., & Harris, H. W. (2007). Enhancing the mission of academic surgery by promoting scientific writing skills. The Journal of Surgical Research, 140(2), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2007.02.018

Dornhoffer, M. K. (2012). Beyond editing: An experience in mentoring provided by an academic health care center’s office of grants and scientific publications. AMWA Journal, 27(4), 147–151.

Eastwood, S., Derish, P. A., & Berger, M. S. (2000). Biomedical publication for neurosurgery residents: A program and guide. Neurosurgery, 47(3), 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006123-200009000-00043

Grzybowski, S. C., Bates, J., Calam, B., Alred, J., Martin, R. E., Andrew, R., Rieb, L., Harris, S., Wiebe, C., Knell, E., & Berger, S. (2003). A physician peer support writing group. Family Medicine, 35(3), 195–201.

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Minor, B. L., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O’Neal, L., McLeod, L., Delacqua, G., Delacqua, F., Kirby, J., Duda, S. N., REDCap Consortium. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Lang, T. A. (1997). Assessing the productivity and value of a hospital-based editing service. AMWA Journal, 12(1), 6–14.

Lim, J. S., Topping, V., Lee, J. S., Bailey, K. D., Kim, S. H., & Kim, T. W. (2019). Effects of providing manuscript editing through a combination of in-house and external editing services in an academic hospital. PLoS ONE, 14(7), e0219567. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219567

Matarese, V. (2016). Editing research: The author editing approach to providing effective support to writers of research papers. Information Today Inc.

Michalski, D. S., & Fowler, G. (2016, Jan 1). Doctoral degrees in psychology: How are they different, or not so different? Psychology Student Network. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/psn/2016/01/doctoral-degrees

North, S. M. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46(5), 433–446. https://doi.org/10.2307/377047

Oh, L., Linden, J. A., Zeiden, A., Salhi, B., Lema, P. C., Pierce, A. E., Greene, A. L., Werner, S. L., Heron, S. L., Lall, M. D., Finnell, J. T., Franks, N., Battaglioli, N. J., Haber, J., Sampson, C., Fisher, J., Pillow, M. T., Doshi, A. A., & Lo, B. (2021). Overcoming barriers to promotion for women and underrepresented in medicine faculty in academic emergency medicine. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open, 2(6), e12552. https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12552

Palmer, S. N., & Mallia, M. (2015). The section of scientific publications at the Texas Heart Institute. Medical Writing, 24(3), 129–131. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000307

Pike, R. (2005). Establishing and maintaining an editorial department servicing researchers in an academic setting. Science Editor, 28(1), 9.

Pololi, L., Knight, S., & Dunn, K. (2004). Facilitating scholarly writing in academic medicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(1), 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21143.x

Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Chu, C., & Joiner, T. E. (2017). Increasing research productivity and professional development in psychology with a writing retreat. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 3(3), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000089

Stefani, K. M. (2014). Developing medical writing support in South Korea. Science Editor, 37(1), 17–18.

Yanoff, K. L., & Burg, F. D. (1988). Types of medical writing and teaching of writing in US medical schools. Journal of Medical Education, 63(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-198801000-00006

Yarrington, J. S., Montgomery, C., Joyner, K. J., O’Connor, M. F., & Wolitzky-Taylor, K. (2023). Evaluating training needs in clinical psychology doctoral programs. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(10), 2304–2316. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23549

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design and conception. Data collection and analysis were performed by MC and JH. Sections of the first draft of the manuscript were written by HM and JH, and all authors reviewed and commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Heather C. McNeill, Jacqueline D. Hill, Myles Chandler, Eric T. Rush, and Martha Montello declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was deemed non-human subjects research by the Children’s Mercy Kansas City Institutional Review Board (#00002920).

Consent to Participate

Because this study did not include human subjects, informed consent was not required.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Previous Presentations: Portions of these data were presented at the Association of American Medical Colleges Central Group on Educational Affairs conference in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on April 5, 2024.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

McNeill, H.C., Hill, J.D., Chandler, M. et al. The Medical Writing Center Model in an Academic Teaching Hospital. J Clin Psychol Med Settings (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-024-10020-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-024-10020-w