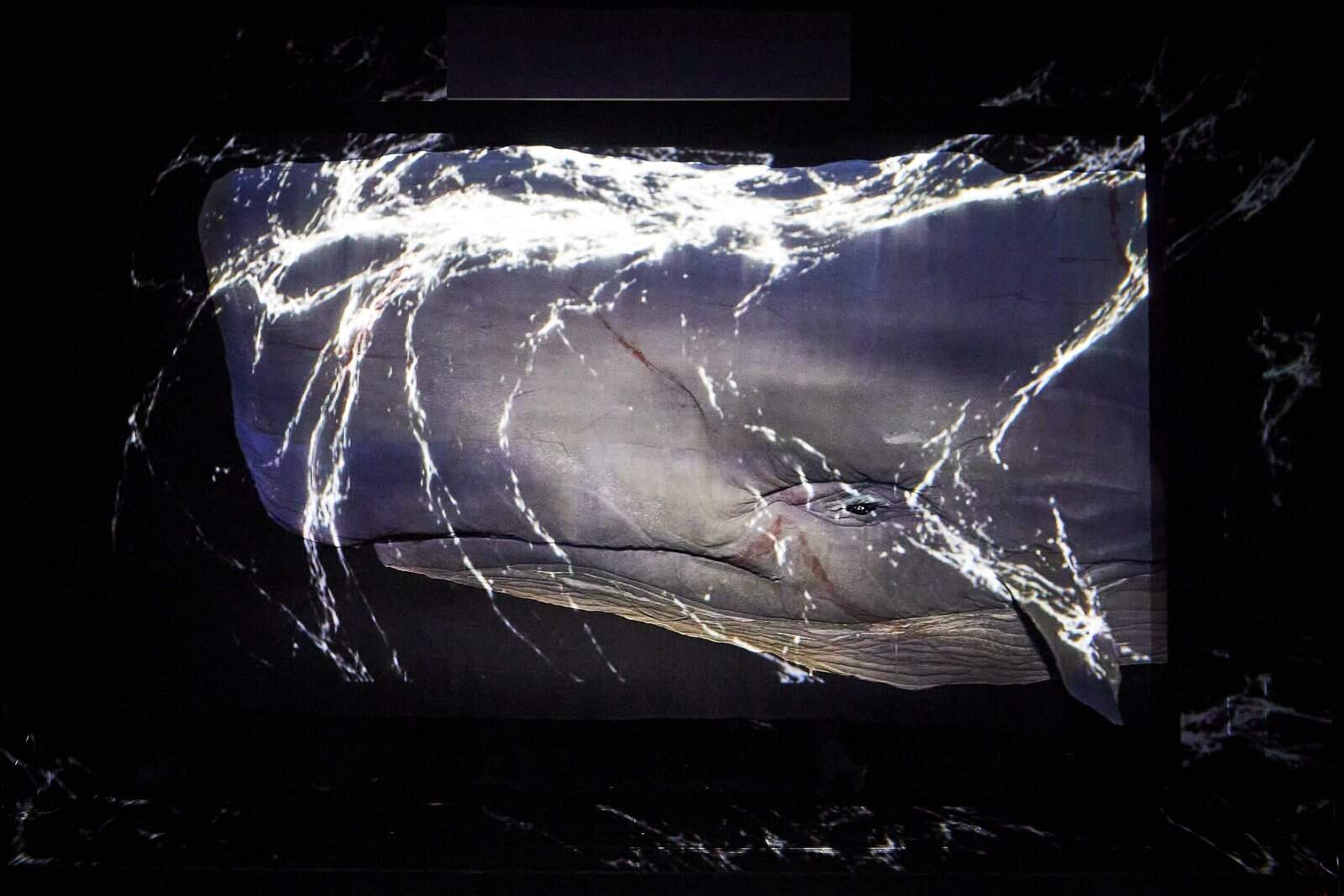

Swarming sea creatures. Strange, ghostly figures like dead men walking. A whirlpool that sucks the world into its abyss. The single, blinking eye of a whale.

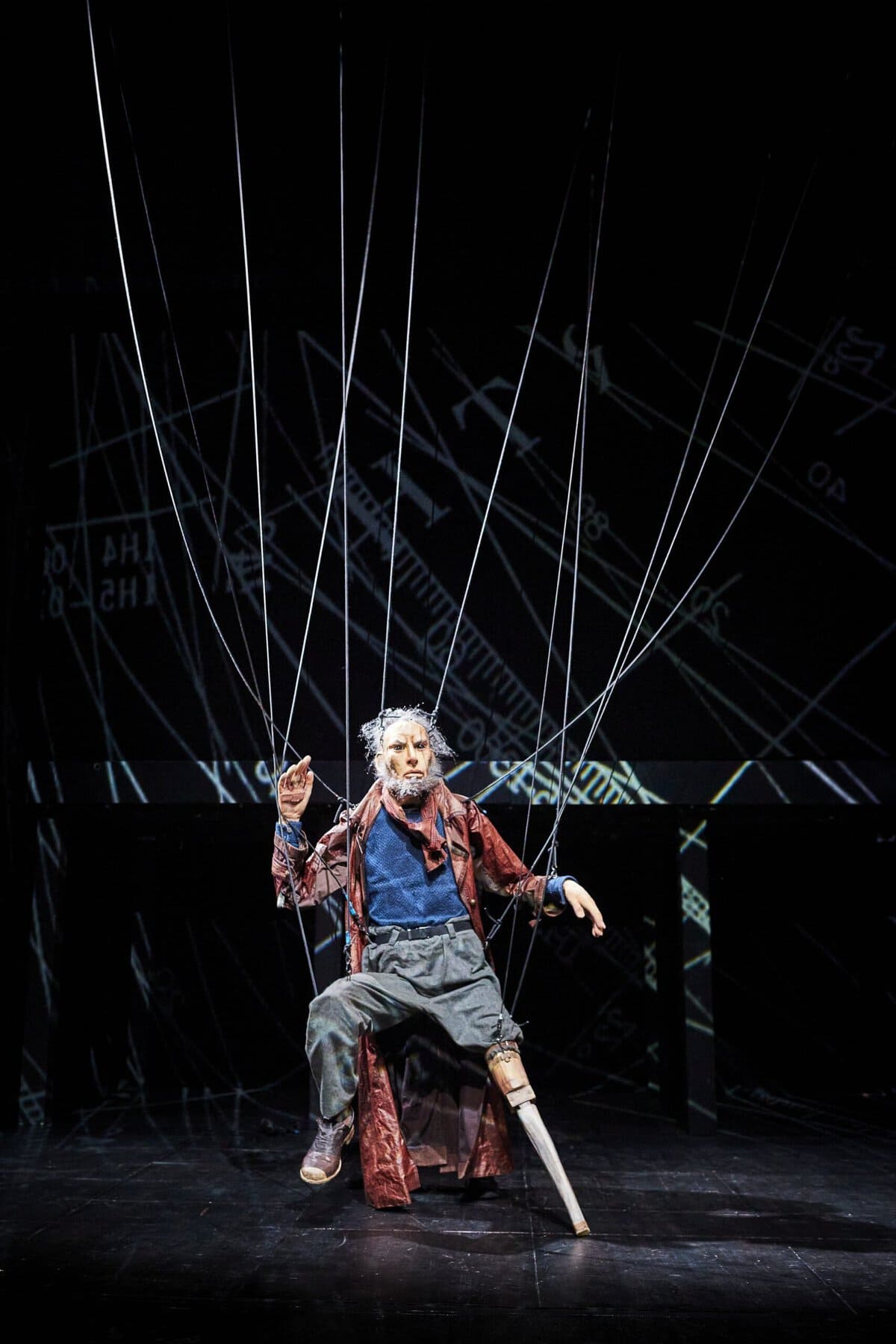

All these, and more, billow by in the trailer to Moby Dick as presented by French-Norwegian puppet theatre company Plexus Polaire. First shown in October 2020, the fourth of the company’s six productions tells the story of the whaling ship the Pequod and its captain’s all-consuming quest to defeat a white whale.

This Friday, as part of the Singapore International Festival of Arts, Plexus Polaire’s version of Herman Melville’s 1851 novel lands for the first time on Singaporean shores. We speak with Plexus Polaire founder and artistic director Yngvild Aspeli on the possibilities of puppetry, the themes of Moby Dick, and the process of adapting Melville’s behemoth for performance.

All the world’s a stage

My first question for Aspeli was very simple: Why puppets?

“For me, it became a question of: Why not puppets?” she swiftly replied.

“I’ve always done visual arts as well as theatre, and puppetry is where these two worlds can meet—where they can have the same weight.”

Aspeli trained at Ecole Jacques Lecoq, a French theatre school, from 2003-2005, before spending three years at ESNAM, France’s national school for puppet arts. Having moved from Norway to France for her studies with other international students, she explains, “this international aspect has been important to me from the very beginning.”

This cross-cultural way of working guided the creation of Plexus Polaire, which “came by little by little” after her final year of study. Today, the company is based in both France and Norway, has over twenty performers from various nationalities, and has toured in countries including Denmark, Canada, and the United States.

But Aspeli’s investment in puppetry is informed not just by her background in art and theatre, but also by a deep awareness of what is unique about the medium—what can be said through puppets that cannot be said, at least not in the same way, by anything else. In the vision statement for Plexus Polaire, she asserts that beyond being an art form, puppetry is also “a way of seeing the world, a language, a state of mind.”

If we strip puppetry down to its bare essentials, even the simple image of the puppet or model being steered by someone else carries unsettling meanings. In a 2019 interview with The Theatre Times, Aspeli describes the ironic inversions of the puppet-puppeteer relationship: “… when the puppet … becomes more alive than the actor who animates it. To somehow move the ‘center’ out of ourselves. When the roles are reversed, and we no longer know who controls whom, we can … look closer at how human beings are controlled by invisible forces around, or inside, themselves.”

Layered complexity

Beyond this, Aspeli is also motivated by puppetry’s capacity to transport us sometime or someplace else. “Puppetry allows us to enter into another dimension in our minds, into the imagination … it somehow collides time and space.” And because puppets can perform in ways human actors cannot, they allow us to transcend the physical, entering more abstract mental and emotional realms. “It’s a very good tool for expressing things that we cannot necessarily explain, but that we can still feel.”

It’s direct, too, blowing past our impulses to intellectualise and communicating through what we see and experience. The way Aspeli describes it, the medium is almost addictive: “It’s a narrative tool that, when you first get hooked on it … it has so many potentials and so many possibilities that it’s then difficult to let go.”

However, she also takes care to emphasise that she has no interest in replacing human actors. Whether visible or hidden, the puppeteers—who, in Moby Dick, control the puppets and do the voices, but also sometimes perform as actors—“are always there as another layer of presence.”

“I’m very much interested,” she adds, “in the relationship between the actors and the puppets, and all the different confusions that this creates—who manipulates who, who’s real and who’s story.”

In Moby Dick, these confusions swirl especially around the figure of Ishmael, the novel’s famously unreliable narrator and sole survivor of its final, watery wreck. Unlike the other characters, Ishmael is largely played by a human actor rather than a puppet. He speaks directly to the audience, and, despite being one of the sailors on the Pequod, often acts as a mere observer of the events on stage.

Besides the handcrafted puppets, Plexus Polaire also makes use of creative sound, light, and video effects, and brings the traditional art form into decidedly contemporary territory. In Moby Dick, specifically, video is used to convey the ocean’s irreducible scale. “It becomes very small as soon as you try to make it on stage … The video was the only thing that managed to capture it.” For Aspeli, furthermore, these new elements only enhance the muddle of truth and artifice that interests her so: “What is puppet? What is projected? What is video? What is light?”

It feels like an accretive approach to storytelling, one that stacks up layer upon layer of meaning. In the same vision statement, Aspeli sets out her creative goals: “To create an expanded reality, where the story is told on several parallel levels. Somehow create a vertical dramaturgy composed by superposed layers, rather than a horizontal line.”

Through various elements, the company leads the audience into a tantalisingly complex experience—where puppets act in uncannily lifelike ways, where human actors flicker in and out of existence, and where the everyday world is upended and solid understandings of fiction and reality turned upside down.

Off the page

But why would a French-Norwegian puppet theatre company take on the daunting task of adapting this classic, but notoriously difficult, American novel?

For one thing, Plexus Polaire has a history of staging literary adaptations—from the 2017 Chambre noire (based on the Swedish novel The Faculty of Dreams) and 2021’s Dracula to their most recent interpretation of A Doll’s House by the playwright Henrik Ibsen. Aspeli describes this process as a kind of serendipitous meeting between a text and the existential questions that preoccupy her. “It’s always a continuous investigation around the complexity of being human, of life: What is bad? What is good? What is madness? What is brilliance? How we are always balancing between these things … and then fall into one side, or another.”

A text like Moby Dick gives her a “structure” through which she can explore these themes: “It becomes the vessel that can hold my research for a while.” At the same time, Aspeli also enjoys how something from a bygone era can become a mirror for the present, revealing shared obsessions: “It’s life and death and love, and the ocean, or nature. It’s the same themes that come back in different forms.”

Of course, Moby Dick’s epic nautical journey also presents enticing staging opportunities. “It has great potential—of the underwater world or diving into the unknown. The mysteries of the whales.”

The nuts and bolts

Still, how can a text as dense as Moby Dick be translated into an hour and thirty minutes on stage? Aspeli explains that ideas for productions often take some time to percolate. “I often read the book, and then go, ‘Ooh, there’s something here, but I’m not ready yet.’ I mean, it’s Moby Dick!”

At some point, though, the idea “resurges,” and it’s then time to read the text over and over—amazingly, in not just English but also Norwegian and French in order to “get beyond the language.” Next begins the process of narrowing down what to bring to life in the play. “What becomes action, what cannot be said differently than with words, what becomes music or atmosphere.”

In Moby Dick’s case, this meant reducing the original 800 pages to about 100 pages of material. “It’s like a concentration or a dissection, going back to the skeleton. What can this animal live without?”

Research for Aspeli tends to centre on the source text rather than extend outwards. Still, she notes that creating Moby Dick entailed understanding how whaling was done back then, as opposed to now: “With what tool? What was the process? […] The whale hunters, how small they are—the madness of it all.”

And the work doesn’t stop with Aspeli researching on her computer or putting things down on the page. A lot of the production is crafted collaboratively, in tandem with her team of performers, artists, and technicians. Even well after the show premieres, she says, “things can find their shape” according to audience reactions: “This is too long. This is not clear enough. Or this is too clear.”

So what should Singaporean audiences expect to see this Friday and Saturday? Aspeli particularly emphasises the production’s use of scale: “We really work with size … to give the feeling of a [life]-sized whale next to the audience.” Viewers can also look out with anticipation for the frantically thrilling hunting scenes, which posed a huge technical challenge—but, Aspeli says with confidence, “I think that how we managed to do it works.”

The play’s the thing

Even if you don’t know anything about Melville’s work, or the real-life events that inspired it, there’s no need to worry. Aspeli is well aware that the story plays out differently for different audiences—whether in America, birthplace of the novel; Norway, with its whaling history; or Chile, home of legendary albino whale Mocha Dick.

“The goal is to touch on something beyond the story or the context, that goes on to what we as human beings are going through, what we are confronted with, and how we deal with life. I wish for the audience to be taken on this journey, and that they might feel safely guided through something that might be scary, confusing, or strange. But, after—you come out, and you’ve been taken away somewhere, and it somehow opens up little new doors in your head.”

My impression is that Aspeli and Plexus Polaire are marvellously at home with the scary, confusing, and strange, and the doors these feelings open—and also that they’re always simmering something new. So what’s next for the company, in the coming year and beyond?

Mostly touring of their current productions Moby Dick, Dracula, and A Doll’s House, Aspeli says, along with some smaller preparatory projects. “The next new creation won’t be till 2026, at least.”

“Now we need some time to play.”

___________________________________

Moby Dick by Plexus Polaire will be performed on 17 May (8 p.m.) and 18 May (3 p.m. and 8 p.m.) at the Singtel Waterfront Theatre at Esplanade, with tickets starting at $38. The Singapore International Festival of Arts, Singapore’s premier performing arts festival, runs from 17 May to 2 June 2024, and boasts a full slate of local and international theatre, music, dance, and children’s programmes. Visit sifa.sg for details.

Header image by Christophe Raynaud de Lage. Responses have been lightly edited for clarity, length, and style.