Only days now remain before a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V rises from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s storied Space Launch Complex (SLC)-41, carrying NASA astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Suni Williams for the long-awaited Crew Flight Test (CFT) of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft. The pair will spend at least eight “docked” days aboard the International Space Station (ISS) conducting a range of flight test objectives before returning to a parachute-and-airbag-aided landing in the southwestern United States.

After being scrubbed two hours prior to launch—with Wilmore and Williams already aboard the Starliner—on the evening of 6 May, following observations of a faulty oxygen relief valve on the Atlas V’s Dual-Engine Centaur (DEC) upper stage, the mission was realigned to fly as soon as 6:16 p.m. EDT on the 17th, before slipping again to No Earlier Than (NET) 4:43 p.m. EDT on the 21st, due to a helium leak in Starliner’s service module that was subsequently traced to a flange on a single reaction control thruster. When launch does occur, Wilmore and Williams will become the first humans to ride a member of the “Mighty Atlas” rocket family since Project Mercury astronaut Gordon Cooper flew his day-long Faith 7 mission way back in May 1963.

And they will add their names alongside “Original Seven” luminaries John Glenn, Scott Carpenter, Wally Schirra and Cooper himself to become only the fifth and sixth people in history to launch atop this most remarkable of rockets. Yet for a slight twist of fate, two others— Original Seven veterans Deke Slayton and Al Shepard—also came tantalizingly close to flying an Atlas themselves.

As described in yesterday’s AmericaSpace story, five Mercury-Atlas missions were launched with mixed success between July 1960 and November 1961, the last of which ferried the chimpanzee Enos on a three-hour, two-orbit mission to trial the abilities of the Atlas-D rocket and the Mercury capsule to fly a living passenger. In the days after Enos’ safe return to Earth, NASA entered high gear for Mercury-Atlas (MA)-6, carrying John Glenn on the United States’ first manned orbital flight.

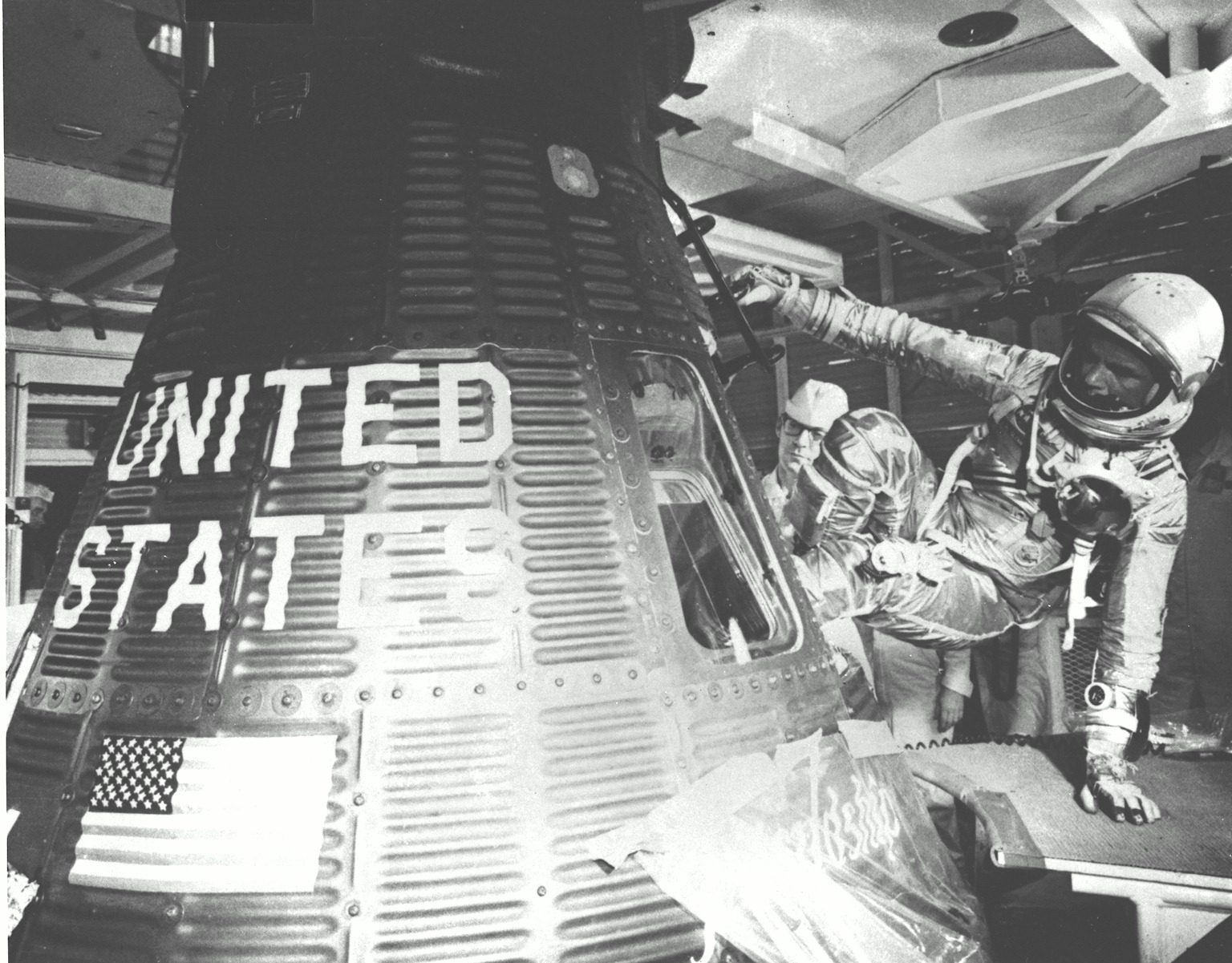

Early on 20 February 1962, after several days due to technical issues pertaining to the rocket’s fuel tanks and poor weather in Florida, John Glenn boarded the Mercury capsule he had nicknamed “Friendship 7” for the first historic launch of a man atop an Atlas. However, the weather around Launch Complex 14 at Cape Canaveral that morning proved dicey, promising only a 50-50 chance of acceptability.

Clouds rolled overhead by the time Glenn arrived at the capsule at 6 a.m. EST, but despite a handful of issues including a broken microphone bracket inside the astronaut’s helmet and a sheared hatch bolt, Friendship 7’s hatch was secured at 7:10 a.m. By the time the pad crew departed the vicinity of the rocket and blue skies began to appear overhead, Glenn’s pulse varied from 60-80 beats per minute and he later reflected upon the eerie sensation of sitting atop the teetering 94.3-foot-tall (28.7-meter) behemoth.

“I could hear the sound of pipes whining below me as the liquid oxygen flowed into the tanks and heard a vibrant hissing noise,” he said later. “The Atlas is so tall that it sways slightly in heavy gusts of wind and, in fact, I could set the whole structure to rocking a bit by moving back and forth in the couch!”

Finally, after another hold caused by a stuck fuel pump outlet valve and an electrical power failure at a tracking station in Bermuda, the countdown continued. At T-18 seconds, the count reverted to automatic and at T-4 seconds Glenn “felt, rather than heard” the Atlas-D’s engines ignite, far below.

At 9:47:39 a.m. EST, with a thunderous roar that overwhelmed Capcom Scott Carpenter’s radioed call of “Godspeed, John Glenn”, the Atlas-D’s hold-down posts were severed and the enormous rocket began to climb away from Earth. That climb appeared cumbersome, as the 260,000-pound (120,000-kilogram) rocket rose under its liftoff thrust of slightly more than 360,000 pounds (163,000 kilograms) from its two boosters and sustainer engine.

“Liftoff was slow,” Glenn recalled in his 1999 memoir, John Glenn: A Memoir. “The Atlas’ thrust was barely enough to overcome its weight. I wasn’t really off until the umbilical cord that took electrical communications to the base of the rocket pulled loose. That was my last connection with Earth.

“It took the two boosters and the sustainer engine three seconds of fire and thunder to lift the thing that far,” he continued. “From where I sat, the rise seemed ponderous and stately, as if the rocket were an elephant trying to become a ballerina.”

For the first seconds of ascent, the Atlas-D climbed vertically, before its automated guidance system placed it onto a northeasterly heading, a transition which Glenn found noticeably “bumpy”. Forty-five seconds after liftoff, the rocket passed through “Max Q”, the period of most extreme aerodynamic forces—a point at which the uncrewed MA-1 had catastrophically failed in July 1960.

“It lasted about 30 seconds,” remembered Glenn. “The vibrations were more pronounced at this point. I did not expect any trouble, but we knew there were certain limits beyond which the Atlas and capsule should not be allowed to go…Since it is difficult for the human body to judge the exact frequency and amplitude of vibrations like this, I was not sure whether we were approaching the limits or not.

“I saw what looked like a contrail float by the window and I went on reporting fuel and oxygen and amperes,” the astronaut added. “The G forces were building up now. I strained against them, just to make sure I was in good shape.”

Successfully launching and passing through the turbulence of Max Q ticked off two of the mission’s four major objectives. A third was completed shortly afterwards when the Atlas-D’s outboard boosters shut down on time, and the central sustainer engine wrapped up Friendship 7’s push to orbit. “There was no sensation of speed,” Glenn wrote later, “because there was nothing outside to look at as a reference point.”

Two and a half minutes after leaving Earth, at 9:50 a.m. EST, the Atlas-D’s Launch Escape System (LES) tower was discarded, “accelerating [away],” wrote Glenn, “at a tremendous clip”. And two minutes after that, the mission’s fourth hurdle—achieving orbit for the first time with a U.S. human crew—was triumphantly achieved.

“Zero-G,” breathed Glenn as the first vestiges of weightlessness made themselves apparent to him. “And I feel fine!”

The final part of this story will appear tomorrow.