Big Brother is Watching You: Why Orwell's Warning is as Relevant as Ever.

Forty years ago, in the year 1984, many commentators predicted that the relevance of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four would dwindle. Its dreadful ‘prophecy’ had failed, at least in the West, they argued. But the book was a warning, not a prophecy, and warnings have longer lives. Orwell’s last and greatest novel can be a cautionary tale of the future, a reminder of the past – or a lens on the present. For some readers, the novel’s mind-warping dictatorship is just a nightmare; for others, it feels much closer to home.

The novelist and essayist Elif Shafak, who has written the introduction to Folio’s new 75th anniversary edition, first encountered the book as an undergraduate in Turkey in the late 1980s. ‘I’ve never regarded Nineteen Eighty-Four as a futuristic dark dystopia,’ she says. ‘Actually, it felt chillingly close. The warning was not about tomorrow, it was about today. I finished it with a sense of urgency.

Shafak left the country for good after she was prosecuted for ‘insulting Turkishness’ in her 2006 novel The Bastard of Istanbul. The Turkey she knew wasn’t a vast, inescapable totalitarian state on the scale of Orwell’s Oceania, but she identified with the psychological struggle of Orwell’s compromised hero, Winston Smith, to remain a free-thinking human being while living in a climate of fear.

‘I think it’s actually a realistic portrait of what happens to human beings under authoritarianism,’ Shafak says. ‘We internalise so much self-censorship and fear without even being aware of it. All kinds of critical thinking are suppressed, and anyone who dares to question anything is immediately regarded as a traitor. Everything is about collective identity

at the expense of erasing individuality.’

Above: Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face - for ever.

Shafak’s experience is just one example of Nineteen Eighty-Four’s ability to live many lives. When it was first published in June 1949, Orwell’s readers understood that he was translating the horrors of Stalinism and Nazism to London in a not so-distant future. Over the past 75 years, however, his satirical analysis of 1940s totalitarianism has reminded readers of many regimes in many times and places. The message he spelled out in a press statement still applies: ‘Don’t let it happen. It depends on you.’

Orwell’s personal experience of tyranny was limited to a few terrifying days in communist-controlled Barcelona in 1937 as a disillusioned anti-fascist volunteer during the Spanish Civil War. But that traumatic brush with a police state gave him a new mission as a writer and ultimately led him to write both Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. They are two halves of the same story: how revolutionary idealism was betrayed and corrupted to form the basis of a dictatorship more oppressive than the regime it had replaced.

After Spain, Orwell devoured accounts of life under the totalitarian jackboots of Hitler and Stalin. While some aspects of Nineteen Eighty-Four were invented or exaggerated, many of its most terrifying elements were directly taken from recent history. The worst had already happened, and could happen again. ‘Orwell’s emphasis on the dangers of power made him very alert,’ Shafak says. ‘He saw, he understood and he sensed how dangerous that road could be. That’s what makes him so relevant to today’s world, with the erosion of democratic norms once again.’

Since 2016, when the election of Donald Trump focused minds on the global resurgence of authoritarian populism, many people have felt what Shafak felt in Turkey – that Winston Smith’s

tormented life in Airstrip One is not such a distant possibility. Orwell combined extreme measures such as torture compounds with more routine manipulations such as propaganda, censorship and hi-tech surveillance. He wanted to remind his readers that democracy and liberty are fragile and require defending.

‘When I reread the novel now, in light of our current global situation, it takes on a far deeper meaning,’ says James Rose, Folio’s Head of Editorial. ‘Part of the brilliance of Nineteen Eighty-Four lies in the fact that some fictional scenarios have become real, even day-to-day – events that we now accept perhaps too readily. In 2020, Comparitech ranked London the third most surveilled city on the planet. Big Brother, it seems, is already watching you.’

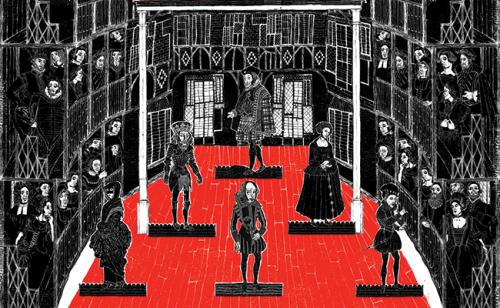

Above: In one combination or another, these three super-states are permanently at war, and have been so for the past twenty-fve years... It is a warfare of limited aims between combatants who are unable to destroy one another

The phrase ‘Big Brother’ itself is just one example of the book’s ingenious use of language, one of the reasons Nineteen Eighty-Four takes up so much cultural space to this day. In order to show how political language can rewire reality and restrict independent thought, Orwell created neologisms that are known to millions of people who have never read the book: doublethink, Newspeak, the Thought Police, the memory hole… Perhaps more popular than any of them is a word coined after his death: Orwellian. More a mood than a precise diagnosis, Shafak notes in her introduction that it is by far the most widely used adjective derived from an author’s name. Ubiquity has its drawbacks.

Many people read Nineteen Eighty-Four when they are young and remember only fragments. Many more don’t read it at all and simply strip it for parts. ‘Lots of people use those neologisms without understanding the context,’ Shafak says. ‘That takes us to a very tricky place. I think Orwell would be very sad if he saw how his terms have been taken out of context and used for quite the opposite ends. What we need to do is slow down, take a closer look and have a nuanced debate about exactly what Orwell was saying.’ Rereading the book, with all its complexities and mysteries, is the only way to take it seriously.

In his journalism as well as his fiction, Orwell dedicated himself to a relentless engagement with the problems of the world he inhabited, constantly challenging his own biases and blind spots as well as abuses of power. This commitment to observing, understanding and speaking out remains an inspiration now that his message has become more urgent than at any time since the end of the Cold War. ‘In the late 1990s and early 2000s there was so much optimism,’ Shafak says. ‘And I believe that led to complacency – an arrogant conviction that history can only lead in a linear direction. Today is better than yesterday, therefore tomorrow will be better than today. But it didn’t happen that way. It is obvious by now that there is no guarantee that tomorrow will be better than today.’ Shafak argues that the ceaseless tsunami of online information that was supposed to liberate us has instead bred a sense of fatigue and impotence in the face of numerous problems. ‘We are in an age of angst, evolving towards an age of apathy. The opposite of goodness is not necessarily evil. It’s numbness.’

Ever since 1949, readers have disagreed about whether Orwell’s bleak conclusion breeds resolve or despair. Winston and Julia’s flimsy rebellion fails, the rebels betray each other, Big Brother prevails. Orwell’s childhood friend Jacintha Buddicom spoke for many when she found Nineteen Eighty-Four ‘a frightful, miserable, defeatist book, and I couldn’t think why he’d written it’.

Above: These rich men were called capitalists. They were fat, ugly men with wicked faces.

But a triumphant ending might have made the novel pure science fiction and diluted its message. Orwell needed to drive home the importance of thwarting a dictatorship before it seizes power. ‘I have asked myself: could he have ended the book in a more hopeful way?’ Shafak says. ‘But this is the end for this kind of story. If he had finished it on a very positive note, we might have said, “Well, the hero always wins”. But he didn’t choose that road, and I like that. I find it much more realistic. Not the pessimism of the heart but the pessimism of the intellect. We have entered an age when we need both a healthy dose of pessimism and a healthy dose of optimism. It is up to us as readers to continue the story and hopefully come up with a better future. The story is not finished.’

Folio's core edition of Ninteen Eighty-Four is available here.

Sign up below to be the first to hear more news on this edition.

Elif Shafak is an award-winning British-Turkish novelist who has published 19 books, including her latest novel The Island of Missing Trees. She is a bestselling author in many countries and her work has been translated into 57 languages. 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in this Strange World was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and RSL Ondaatje Prize. The Forty Rules of Love was chosen by the BBC among 100 novels that shaped our world. Shafak holds a PhD in political science and she is an honorary fellow at St Anne's College, Oxford University. She is a Fellow and a Vice President of the Royal Society of Literature. An advocate for women's rights, LGBTQ+ rights and freedom of expression, Shafak contributes to major publications around the world and was awarded the medal of Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.