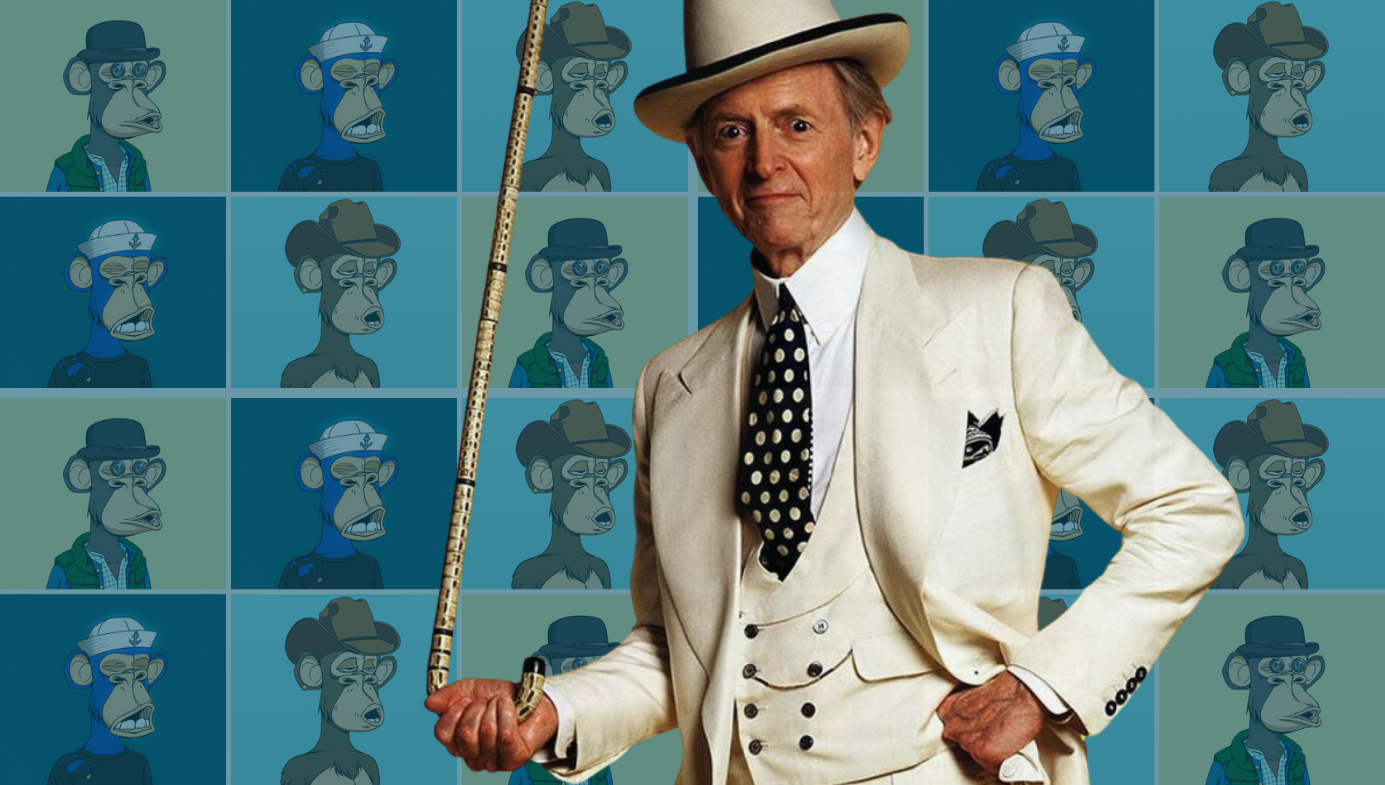

Less Than Half ‘A Man in Full’

One of US television’s most experienced and talented writers has made a mess of Tom Wolfe’s second novel.

NOTE: The following essay discusses A Man in Full—the new Netflix series and the Tom Wolfe novel on which it is based. There are spoilers throughout.

I.

The new six-part Netflix miniseries A Man In Full is a binge-worthy piece of entertainment that bears little relation to the 1998 Tom Wolfe novel of the same name on which it is based. The show is written and created by David E. Kelley, who is a master of the genre, having previously written and produced TV adaptations of Liane Moriarty’s novels Big Little Lies and Nine Perfect Strangers, Jean Hanff Korelitz’s You Should Have Known (the source of HBO’s The Undoing), Michael Connelly’s The Lincoln Lawyer, Stephen King’s Mr. Mercedes, and many others.

Unfortunately, Kelley is not up to the task of adapting Tom Wolfe. Wolfe wasn’t just an entertainer, he was also a sharp social satirist. His novels were not just meant to amuse, they also provided trenchant critiques of American life. And the material in Wolfe’s book that Kelley has either reworked or stripped out entirely is exactly the stuff that would have made it both controversial and highly relevant to our current political and cultural moment.

Wolfe’s novel is about Charlie Croker, a 60-year-old Atlanta business tycoon whose financial empire is in peril. Croker owns a network of frozen-food warehouses across the US, but his pride and joy is Croker Concourse, a 40-story skyscraper-cum-commercial complex located near the outskirts of Atlanta. Croker is the star around which all of the other characters in the novel orbit. The most distant of these satellites is Conrad Hensley, a white 23-year-old married father-of-two who lives 2,800 miles from Atlanta in Oakland, California, and works in one of Croker’s warehouses. His dream is to purchase a condo unit in nearby Contra Costa County and raise his family in middle-class comfort. For most of the novel’s immense length, Croker and Hensley are unaware of each other’s existence but Wolfe draws the two narrative threads together for the finale.

Other satellites include Serena, Croker’s much younger second wife and a shopaholic; Croker’s first wife, Martha; Raymond Peepgass, a loan officer who has always toadied up to Croker but has turned against him as Croker’s finances sour; Harry Zale, a “workout specialist” at PlannersBanc, who tries to crush Croker’s ego when the loans go bad; Wes Jordan, the young black mayor of Atlanta; and Roger White III (nicknamed Roger Too White), a young black Atlanta attorney who acts as an intermediary between Croker and the mayor. Croker may be a star, but he’s a dying star, and his collapse threatens to pull everyone around him into the black hole of his financial ruin. Most of these characters are scrambling to distance themselves from Croker in one way or another—only Hensley tries to help when he finally sees the trouble Croker is in. This development is ironic because Hensley’s life falls apart as a result of Croker’s callousness.

As Croker’s financial problems become critical, his accountant advises him to sell off a 29,000-acre plantation that Croker primarily uses for hunting quail. The plantation is listed as a business asset because Croker occasionally entertains clients there, but it generates no income and costs a fortune to maintain. Rather than part with his beloved plantation, Croker opts to sack 15 percent of the staff working in his frozen-food warehouses instead. As a result, Conrad Hensley and hundreds of other employees across the nation are thrown out of their jobs so that Croker can hang on to his quail-hunting plantation.

While Hensley is out job-hunting, his car is unfairly impounded. Unable to afford the impound fee, he breaks into the lot to steal his vehicle back and gets arrested. He is sent to Santa Rita jail, a violent county lock-up about 30 miles south of Oakland, largely controlled by racial gangs. There, Hensley finds comfort in an anthology of writings by famous Stoics, particularly Epictetus, Agrippinus, and Zeno. It is difficult to overstate the importance of Stoic philosophy to Wolfe’s novel—he seems to have written it to illustrate how Stoicism might be applied in everyday American life. Hensley’s life is transformed by his introduction to the Stoics, and much later in the book, Croker’s life will be similarly altered after Hensley introduces him to the same thinkers.

Stoicism teaches Hensley to speak the truth as he sees it no matter what the dangers may be. After he embraces this approach, he loses much of his fear of jail. His tormentors detect a change in him—a willingness to fight rather than meekly acquiesce to their demands—and they begin to leave him alone. In a plot twist straight out of an ancient Greek tragedy, Hensley is sprung from jail when an earthquake destroys the facility’s perimeter wall and he slips off into the night. Eventually, through a complicated—and not very believable—series of events, he ends up living in Atlanta under an assumed identity where he lands a job assisting invalids in their homes. When Charlie Croker is discharged from hospital after he has an artificial knee implanted, Hensley becomes his home-care assistant. These plot contrivances work because Wolfe’s satire is modelled after the works of Dickens and Thackeray; it isn’t intended as a work of realism.

By the time he meets Conrad Hensley, Charlie Croker is experiencing a crisis of conscience. One of the novel’s threads involves a Georgia Tech running back named Fareek “the Cannon” Fanon, a black man rumoured to have raped a white college girl named Elizabeth Armholster in his dorm room. Elizabeth has told her parents about the rape but refuses to report it to the police. Her father, Inman Armholster, is another wealthy Atlanta businessman and an old friend of Charlie Croker’s. The black mayor of Atlanta, Wes Jordan, suspects that a race riot might erupt if Fanon, a local sporting hero in the black community, is arrested for raping a rich white girl, and Jordan believes that Croker is uniquely positioned to help him forestall that crisis. Croker was a Georgia Tech football hero back in the 1950s and is now highly regarded in the white community. Mayor Jordan has promised to intercede in Croker’s problems with PlannersBanc if Croker will agree to hold a press conference at which he declares that Fanon is innocent of rape.

Croker is a bigot and believes that Fanon is probably guilty. What’s more, by publicly defending Fanon against the rape charge to get relief from the bank, Croker will also destroy his friendship with Inman Armholster. Croker has just enough integrity left to feel guilty about accepting the mayor’s offer, but after Conrad Hensley introduces him to Stoicism, he has a change of heart. At the scheduled press conference, with the mayor standing behind him, he announces that he has been threatened with financial ruin if he doesn’t defend Fanon. But he has decided that he is less bothered by the idea of financial bankruptcy than he is by the idea of moral bankruptcy. He then tells his creditors to come and take his assets, including his beloved Croker Concourse, and vows not to contest the seizures. He leaves with his wife and young child and becomes a sort of Jordan Peterson-like evangelist of Stoicism with his own show on the Fox network.

II.

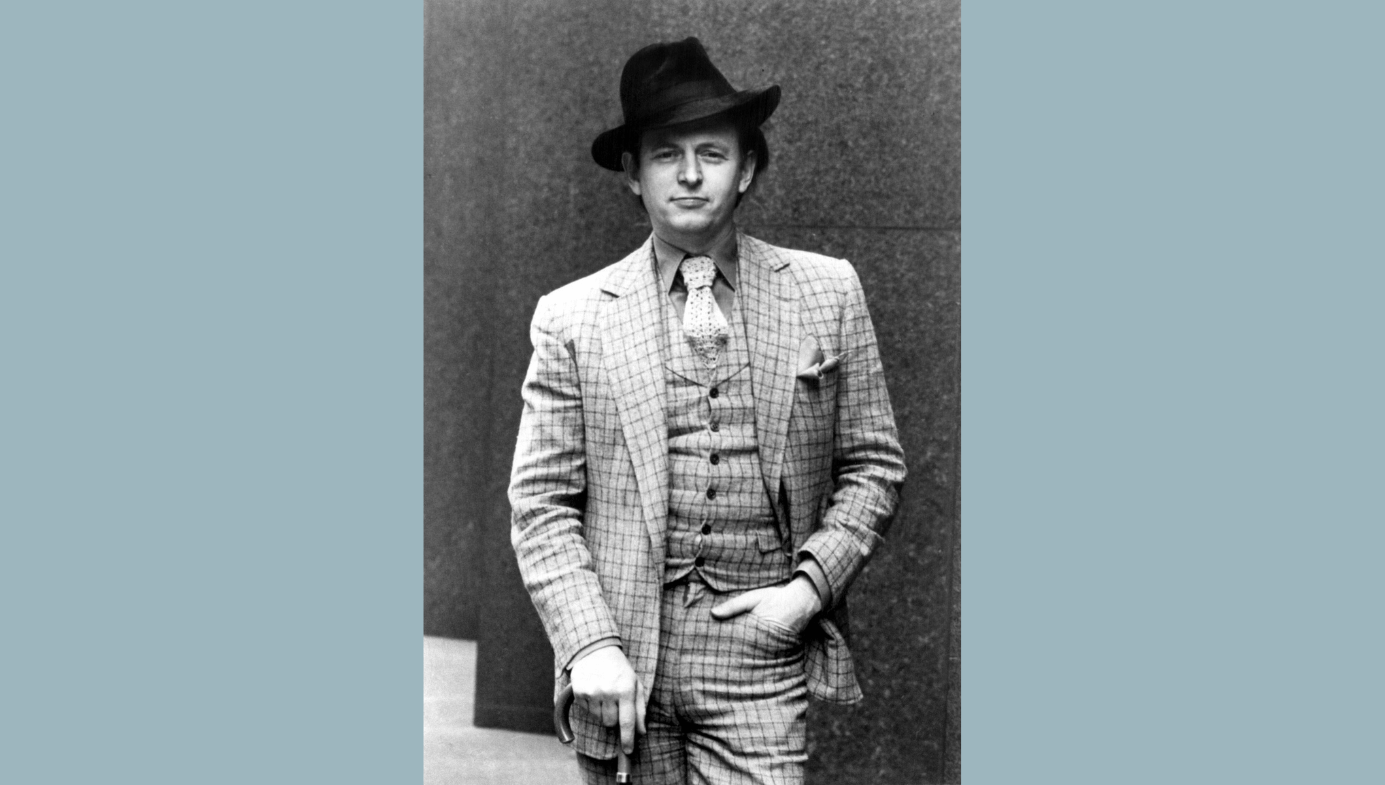

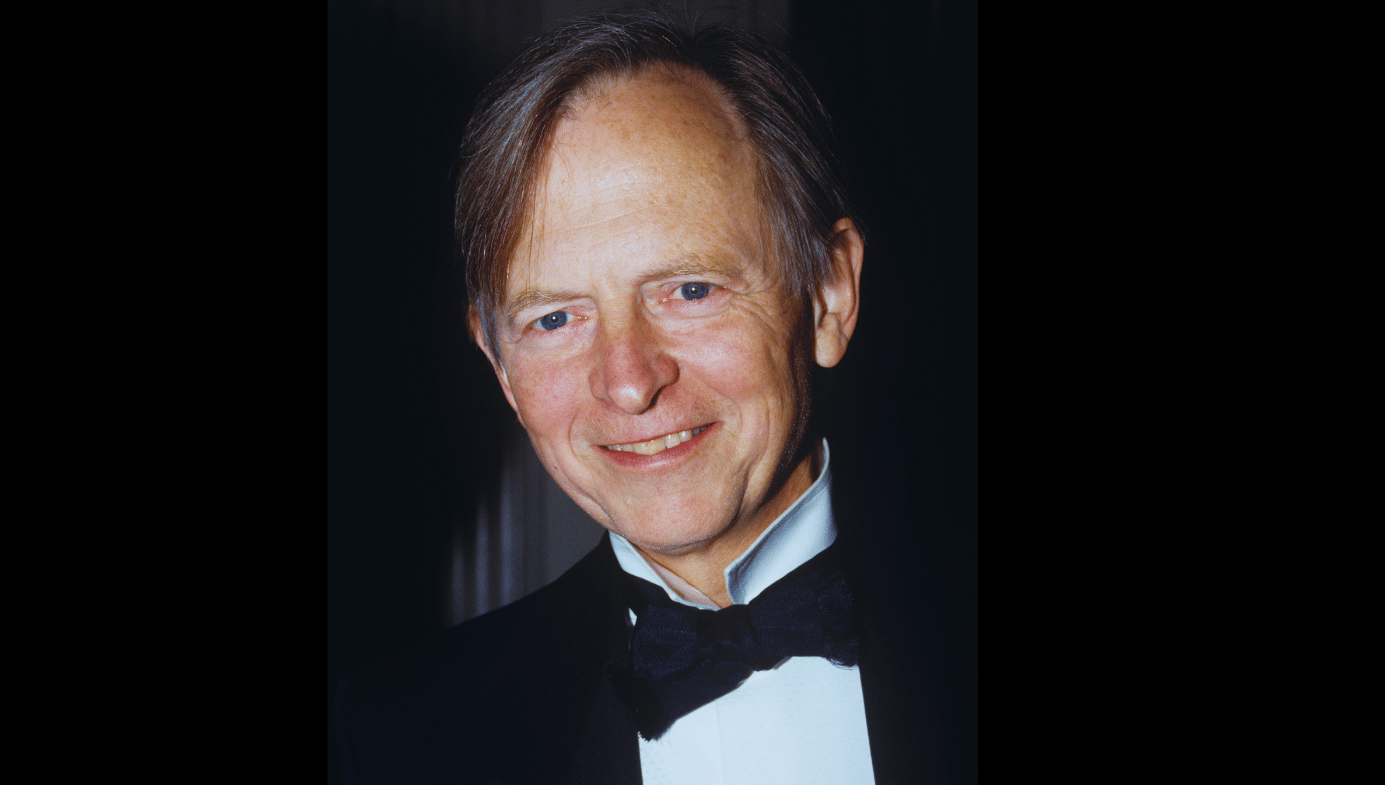

Wolfe’s book was, among other things, a shot fired across the bow of American literature. He believed that American novelists in the late 20th century had turned inward at a moment when America’s cities had become as big and fascinating as the London that Dickens had written about or the Paris that Balzac and Zola had written about in the 19th century. This, he argued, was why the New Journalism that he and other nonfiction writers were producing in the 1960s and ’70s was more important and interesting than the fiction being produced by writers featured in the pages of the New Yorker during that era. (Wolfe had a special disdain for the New Yorker and the feeling was mutual; William Shawn, the magazine’s editor, hated the New Journalists.)

Wolfe also believed that popular novelists like Joseph Wambaugh, who wrote about the grand menagerie of Los Angeles, were doing more important work than the so-called serious literary writers, who were focusing primarily on sex (John Updike’s Couples) or ennui (much of Ann Beattie’s work) or literary gamesmanship (anything written by a postmodernist). In an introduction to the Franklin Library edition of The Bonfire of the Vanities, Wolfe wondered, “where were the novels of Los Angeles, of San Francisco, of Houston, of Dallas, of Chicago, of Atlanta, of Miami?” Eleven years later, in the introduction to A Man in Full, he wrote, “Now … I don’t merely wonder, I am dumbfounded. Only one year left in the millennium, and our novelists continue to ignore the feast set before them, and the American novel continues to wither away from anorexia.”

Although Wolfe didn’t mention any names in this introduction, some of America’s most prominent men of letters clearly felt they had been indicted. John Updike, John Irving, and Norman Mailer all rained literary scorn on A Man In Full. Updike hacked away at it in the pages of the New Yorker:

The preeningly expert architectural details, the avid sartorial specifics, the infallibly lively decors in all their dubious taste, the price tag attached to everything worn or inhabited, the painstakingly spelled-out accents, the explosive onomatopoetics … all remind the reader of the vigilant, mischievous, but rather disapproving presence of the writer, for whom America comes down to noise, trash, and vanity.

Thus, Updike reduced a 742-page novel that Wolfe worked on for 11 years to three unpleasant nouns. From his Olympian perch, he concluded:

This is high-minded, but A Man in Full still amounts to entertainment, not literature, even literature in a modest aspirant form. Like a movie desperate to recoup its bankers’ investment, the novel tries too hard to please us. … Wolfe shares a name with another profuse, all-including Southern writer [Thomas Wolfe] who failed to be exquisite. Such failure would not seem to be major, but in the long run it is.

It’s too early to know what the long run has in store for either writer, but the short run has been far kinder to Wolfe than to Updike, at least in terms of popularity. A Man in Full has over a thousand Amazon reviews, The Bonfire of the Vanities has more than 4,000, and The Right Stuff has more than 5,000. Updike reliably turned out a book a year for most of his career. His 1999 book—a collection of reviews titled More Matter that includes Updike’s scathing review of A Man in Full—currently has 22 reviews on Amazon.

Wolfe invented or popularised phrases that have become a permanent part of our language: The New Journalism was his coinage, as were terms like radical chic, the right stuff, the Me Decade, haemorrhaging money, and so on. This decade alone has brought us TV adaptations of both A Man in Full and The Right Stuff, as well as a documentary, Radical Wolfe, about the life of the author. As I write this, A Man in Full is Netflix’s fourth most-watched show. The third most-watched film on Netflix is Unfrosted, Jerry Seinfeld’s new film that Slate noted includes homages to The Right Stuff. Updike, meanwhile, seems to be fading from sight in the manner of Booth Tarkington, another writer who, like Updike, won two Pulitzer Prizes for his fiction before vanishing into obscurity. It’s hard to imagine a popular new film spoofing Updike’s work because most viewers wouldn’t get the reference.

Wolfe’s novel was a huge commercial success. It sold out its first hardcover printing, and then sold out seven additional printings of 25,000 copies each. It spent ten weeks atop the New York Times’ fiction bestseller list. Wolfe was featured on the cover of Time magazine. The book was one of the most talked-about works of fiction in America as we approached the end of the so-called American century. It was almost certainly the last truly big and important American novel of that century. Just as Theodore Dreiser had ushered in the new century with Sister Carrie, a 1900 book about the American Dream gone rancid, Wolfe had ushered it out with A Man in Full, a novel on the same theme.

This massive success seemed to rile Updike, Mailer, and Irving. In the pages of the New York Review of Books, Mailer declared that Wolfe was no longer a real writer but rather a creature who “lives in the King Kong Kingdom of the Mega-bestsellers.” Irving went on a profanity-laced tirade when a Canadian TV interviewer asked him about the book. “Wolfe’s problem is he can’t fucking write! He’s not a writer! Just crack one of his fucking books! Try to read one fucking sentence! You’ll gag before you can finish it!”

Wolfe wrote amusingly about this triumvirate in an essay titled “My Three Stooges,” which can be found in his essay collection Hooking Up. He noted that all three men published a novel within a year or so of A Man in Full—Updike’s Bech at Bay, Mailer’s The Gospel According to the Son, and Irving’s A Widow for One Year—none of which attained anywhere near the kind of cultural prominence achieved by A Man in Full. Wolfe ascribed their displeasure with A Man in Full to jealousy and asserted that while his antagonists’ careers were in decline, his own was still ascendant. He seemed to be having the time of his life. Sometimes, laughing well is the best revenge.

III.

Alas, almost all of what made Wolfe such an interesting writer—his brash fearlessness, his contrarian wit and perspicacity—is absent from David E. Kelley’s adaptation of A Man in Full. While not entirely unenjoyable, it is nevertheless a relatively tepid bit of storytelling that bears only a passing resemblance to its source material.

Kelley’s contemporised miniseries stars Jeff Daniels as Charlie Croker, whose story roughly tracks that of Wolfe’s protagonist for the first half of the novel. His corporate finances are a shambles and unless PlannersBanc rewrites or forgives his loans he will go bankrupt. The Conrad Hensley thread of the narrative has also survived the adaptation process, but with significant alterations. Hensley has become a young black man whose pregnant wife Jill is Charlie Croker’s executive secretary. Hensley drives a forklift in one of Croker’s Atlanta warehouses and he is arrested for striking back at a violent white cop during a parking violation dispute and sent to the county jail by a racist white judge.

Black Lives, Kelley is at pains to stress, do not Matter to Atlanta’s criminal justice system. Croker has a warm relationship with his secretary so he lends her incarcerated husband the services of his attorney Roger White (the “Too White” nickname has been tactfully excised). While White labours to get justice for his client, Hensley languishes in jail and defends himself from a white supremacist prison gang after he reports their rape of another inmate. Stoic philosophy makes no appearance in the story at all, and Hensley is eventually freed when White plays the cop’s incriminating bodycam footage for the court. Hensley and Croker never meet.

The rape subplot has also been changed. One of the interesting ironies of Wolfe’s novel is that although Croker redeems himself by refusing to collaborate in a piece of corrupt political theatre, Wolfe strongly suggests that the rape allegation may in fact have been invented by the victim. So while Croker is being true to himself by refusing to exonerate a black sporting hero, he may actually be wrong on the facts. In a post-#MeToo post-BLM cultural climate, Kelley appears to have decided that this won’t do at all.

So in the miniseries, the accused rapist is a sleazy white businessman running against Mayor Jordan and the victim is an Asian friend of Croker’s ex-wife Martha, who insists that the “rape” was actually a drunken but consensual one-night stand. At the presser, Croker refuses to accuse Jordan’s political rival of rape (as he has pledged to do to get the creditors off his back), but there is no speech about moral integrity and the viewing public are therefore none the wiser about this redemptive act. And since Stoic philosophy plays no role in the story, we are asked to believe that Croker’s change of heart is motivated by a sudden and impulsive desire to set a good example to his son.

Wolfe’s massive novel has many subplots and secondary characters that I haven’t even mentioned yet. One of these involves a romantic relationship between Croker’s ex-wife Martha and PlannerBanc’s loan officer Raymond Peepgass (renamed Peepgrass in the miniseries for some reason), who both envies and admires Croker. In the miniseries, Peepgrass is lustily carousing with Martha in Croker’s former home when Croker learns that the younger man is secretly putting together a syndicate to purchase Croker Concourse from the bank. When Croker bursts in on them, a fight ensues, and as Croker throttles the naked Peepgrass to death, he suffers a fatal heart attack. And on that unsatisfactory note, Kelley ends Croker’s ten-day flirtation with financial and personal ruin.

Wolfe’s novel is the story of Charlie Croker’s gradual transformation from a greedy megalomaniacal real-estate tycoon into a thoughtful husband and father who sets out to spread a philosophy that he believes will strengthen the character of all Americans. The miniseries is the story of Croker’s transformation from a greedy megalomaniacal real-estate tycoon into a greedy megalomaniacal murderer (although Kelley suggests that the murder may be at least partly an accident caused by a seizure in Croker’s hand that prevents him from relaxing his grip on Peepgrass’s throat). This is not an especially emotionally rewarding moral arc.

Wolfe evidently believed that even a coarse, self-involved multi-millionaire could become a decent human being under the right circumstances. In this sense, his thinking seems to reflect that of Republicans who hoped that the seriousness and dignity of the office of the President of the United States of America would somehow moderate the character of Donald Trump. (British Tories were probably hoping the same thing about Boris Johnson.) Wolfe’s story may not be especially convincing, but Kelley’s version of Croker experiences no coherent character evolution at all. His redemption at the presser podium is perfunctory and unpersuasive, and since he dies in the act of murder, he never actually suffers the financial and reputational consequences of his decision to cross the mayor.

Race is a factor in both the book and the miniseries, but in the miniseries it is handled with no nuance at all. Conrad Hensley is not only the victim of a racist system, but he and his black attorney are the only really decent men in the whole story. Racism, Kelley reminds us over and over again, is bad. Wolfe’s handling of race and racial politics is more complex and ambivalent. Even Updike admitted that “in a strange but honorable way Wolfe has attempted a Great Black Novel … he has worked hard on the novel’s black sections, making them morally elaborate as well as intensely observant.” The ambiguity surrounding the rape accusation is illustrative. Elizabeth Armholster, we learn, actually initiated the sexual encounter with Fanon, and only claimed to have been a rape victim after some of her lily-white sorority sisters caught the two of them in bed together.

Race and class figure in most of the subplots of Wolfe’s novel, and racial slurs crop up repeatedly. Wolfe’s black characters muse on the difference between the terms “African-American” and “black.” An entire subplot about a network of Asian-American truck drivers that helps to move illegal immigrants around the country is absent from the miniseries, but it provided the novel with an additional racial dimension. What’s more, it emerges that Charlie Croker first acquired the land for Croker Concourse by cynically inspiring a racial conflict to temporarily depress property values in the neighbourhood. This scheme meant that he had to sell out an old friend of his, a sad-sack racist who leads a pathetic chapter of the Ku Klux Klan.

The economics of Wolfe’s book also make more sense than they do in Kelley’s miniseries. In the novel, we are told that Croker foolishly bought into the idea that “edge cities”—small, discrete commercial and residential hubs located just outside of major American cities—were the future of American real estate. Consequently, Croker Concourse was built on the outskirts of Atlanta, which is why Croker is now having trouble leasing out space in it. In Kelley’s miniseries, Croker Concourse is located right in the heart of downtown Atlanta, a giant phallic symbol of Corporate America at its brashest, and no effort is made to explain why the building is doing more poorly than its neighbours.

Likewise, in the miniseries Conrad Hensley’s wife is the executive secretary to one of the most important businessmen in Atlanta, a job that would pay handsomely. In Wolfe’s book, Croker reveals that he pays his executive secretary $90,000 a year—about $170,000 in inflation adjusted dollars. And yet Jill is unable to afford a real trial attorney, which is why she has to accept Croker’s loan of Roger White’s services. White is a corporate attorney who earns a million dollars a year working for Croker, but he has never handled a criminal case. His wife is also a highly paid attorney. As African-Americans, they are both horrified that Hensley has been thrown in jail by a racist system, but they never even discuss the possibility of using their own assets to raise bail. Between them, Jill Hensley and the two Whites should have been able to raise the $250,000 necessary to post bail without any outside help. The Whites’ house alone probably has $250,000 in equity in it.

I am a longtime fan of both Tom Wolfe and David E. Kelley. In the 1990s, when I was writing about real estate for the Northern California Real Estate Journal and the Sacramento Business Journal, I read an interview with Wolfe in which he mentioned that his next novel would deal in part with San Francisco-area real estate. With characteristic hubris, I sent him some clips of my freelance journalism and offered my services as a researcher if he was in the market for an expert on Northern California real estate (unsurprisingly, he never responded). Nevertheless, I obtained autographed copies of both the Franklin Library’s collector’s edition of A Man in Full and Farrar Strauss & Geroux’s hardback bookstore edition (I have autographed copies of all four of Wolfe’s novels).

David E. Kelley’s Picket Fences and Ally McBeal were two of the best TV shows of the 1990s and his name usually indicates quality entertainment. So, when I read that Kelley would be adapting a Tom Wolfe book for a Netflix miniseries, I was excited. I spent several years working in an Amazon warehouse that was full of minority employees and the experience frequently reminded me of the food warehouse described in Wolfe’s novel. In some ways, my life resembles that of Wolfe’s Conrad Hensley—a white working-class Northern Californian bookworm with big dreams. And now I was going to see my avatar on Netflix! Alas, Kelley preferred to reimagine Hensley’s story as a post-Floyd narrative designed to flatter the political beliefs of the contemporary activist class. Wolfe’s Charlie Croker, meanwhile, is both darker and more complex than in Kelley’s interpretation. As portrayed by Jeff Daniels, he is like a hybrid of Foghorn Leghorn and Thurston Howell III.

A Man in Full’s 742 pages juggle dozens of characters and subplots that required Wolfe to keep a lot of balls in the air. Kelley’s adaptation resembles a suburban dad juggling three oranges for the amusement of his toddlers. Consider the contrasting portrayals of Croker’s ex-wife, Martha. In both versions, Martha is wooed—and, to some extent, won—by Raymond Peepg(r)ass. As noted, in the miniseries, Martha’s new lover is murdered by her enraged ex-husband. Wolfe handles the conclusion of the relationship with more subtlety. While Croker is telling a press conference that he plans to surrender all his assets to the bank, Martha and Raymond are watching it on TV in the living room of Martha’s mansion. Raymond is gleeful, and starts to gloat about how humiliating it must be for Croker to be ruined in this manner for all the world to see. But Martha sees the broken man she once loved finally regaining the dignity and integrity that attracted her to him in the first place. Wolfe never says so, but this is clearly the end of her affair with Peepgass.

IV.

Still, Wolfe’s critics were not entirely off the mark—his big novel has some big faults. Upon re-reading it after I watched the series, I found myself even more put off by his excessive use of onomatopoeia than Updike was. Here’s a representative sample (the ellipses are all in the original):

Buh buh buh buh bubba boooooo uh-ooooooooooo, the long soft ripe soupy notes of Grover Washington’s saxophone… Scrack scrack scrack scrack scraaaaaaaaacccccccckkkkkkkkkk, the grinding screech of the attic fans… Motherfuckin’ motherfuckin’ motherfuckin’ motherfuckin’, the motherfuckin’ chorus of one and all… Thragoooooooom thragoooooooooom, the roar of the toilets flushing… Glug glug glug glug glug glug glug, the sucking noise they made when they finished flushing… and then Motherfuckin motherfuckin’ motherfuckin’ motherfuckin all over again.

That’s a description of what Conrad hears when he sits in his jail cell at night. Stuff like that appears on nearly half of the book’s pages, and it starts to grate like a jailhouse ceiling fan. I once attended a lecture by John Irving at which he noted that the qualities for which a writer is praised early in his career can often become liabilities later on. This certainly happened with Irving—his breakout novel, The World According to Garp, was praised for its elaborate Dickensian plot and that seemed to inspire him to create ever more baroque—and unwieldy and tiresome—plots in many of his subsequent novels. The same thing seems to have happened to Wolfe. In his early writings, he was praised for his skill with onomatopoeia, which even then wasn’t really all that impressive. By the time of A Man in Full that inventive tic had become a weight on his prose.

Wolfe was also proud of his familiarity with cutting-edge American slang, but by the time he got around to writing A Man in Full his ear for vernacular seemed to have deserted him. Redundantly, he tells us that “I’ve got your back” is “an Atlanta street expression meaning ‘I’m behind you—I am your follower—and I’ll protect you against attacks from the rear.’” This expression is actually believed to have originated with World War II fighter pilots. Likewise, Wolfe was so impressed by his discovery of the term “hooking up” as a euphemism for “having sex” that he not only crowed about it in A Man in Full but published a book titled Hooking Up two years later, featuring an essay on the term. But, as language maven William Safire, among others, pointed out, the term “hooking up” as a reference to any kind of human get-together entered the language in 1903. Its sexual connotations came later but they never became, as Wolfe seems to think, its primary definition.

Wolfe also seems to have thought that he was adept at parodying rap lyrics. I’m not a fan of rap music, but I’ve never heard lyrics as awful as the ones Wolfe creates for A Man in Full:

Nine to five you park yo’ butt

Beneath the bitch box on the wall

And lap up all that crap inside

The rut they make you crawl.

So, yo, go buy yo own death, bro,

And die on the installment plan,

Fo they cut yo nuts and hang you

From the necktie on the bald man.

(I chose that example because it contains less profanity than most of his other rap lyric spoofs, but it is by no means the worst.)

In A Man in Full, Roger White and Wes Jordan, two 30-something black men complain to each other about the fact that the young black athlete Fareek Fanon has pierced ears and wears a gold necklace. Even back in 1998, nobody under the age of 65 would have been surprised to see a famous athlete with pierced ears and bling around his neck. Certainly, men like these wouldn’t have bothered to comment on it. In spite of all his research, Wolfe’s characters—regardless of their age or race—seem to think like old white men. And when he transcribes the dialogue of a white character like Charlie Croker, he usually renders it in fairly standard English, and inserts idiosyncrasies of pronunciation afterwards in italics, like this:

“Nobody’s talkin’ about not payin’ you back,” snapped Croker. “We’re talkin’ about something very simple.” Sump’m veh simple.

But when he presents the dialog of a person of colour, he usually tries to render it all in dialect, which is often undecipherable. Here’s one of Conrad’s cellmates in prison:

“Bummahs man,” said Five-O. “I only tryeen fo’ make da bullet clip, li’dat, ass why.”

Probably the biggest flaw in the novel is Wolfe’s treatment of women. The wives in A Man in Full are almost always portrayed negatively. Conrad Hensley’s wife is a shrew, and so is her mother. Raymond Peepgass’s wife is a cold-hearted social climber described as “loud” and “bossy,” which is why he has destroyed his marriage by hooking up with a Finnish bimbo. Peepgass now lives in a low-rent apartment building, and from his windows he can hear married couples arguing in the backyards of the neighbouring houses. “So he kept the windows open, and now he could hear one of the young wives screaming at her husband—it was mostly the young wives who screamed—sometimes the husband but mostly the wife…”

Wolfe’s men are always leaving their shrewish first wives for bimbo second wives or mistresses, and Wolfe seems to be incapable of writing a wife who is neither one nor the other. Charlie’s young second wife Serena is a bimbo whose lavish spending is at least partly responsible for her husband’s financial woes. Martha is a pleasant woman but she is heavy (a fatal flaw for a woman in Wolfe World). Here is Raymond Peepgass as he contemplates proposing marriage to Martha: “What could she do about that … thickness in the neck and shoulders and upper back? Anything? Probably not. Would she be presentable? I’m only forty-six. She’s fifty-three. Would it be embarrassing to take her places as my wife?”

David E. Kelley’s TV work, on the other hand, has almost always featured a variety of intelligent and interesting women. Like the men, the women in Kelley’s A Man In Full are not complex, but at least they tend to be smart and decent human beings. Martha (played by Diane Lane) is kind and smart. Charlie’s second wife Serena (Sarah Jones) is competent in matters of business and the household and she’s a loyal and understanding wife to a husband in physical and financial decline. The character isn’t developed as fully as her husband, but at least she isn’t the two-dimensional embarrassment of Wolfe’s novel. Roger White’s wife (Jerrika Hinton), Conrad Hensley’s wife (Chante Adams), and even Martha’s friend Joyce (Lucy Liu) are all smart and highly competent. (A recurring complaint I have about Kelley’s various miniseries is that they all seem to include a role that would be ideal for his wife, Michelle Pfeiffer, but she never appears in any of them.)

But while Kelley’s adaptation is better than Wolfe’s novel in some respects, it fails entirely as social satire. Although it has been updated to the present day, it really has absolutely nothing of interest to say about the way we live now. Its message—if indeed it has one—seems to be: “Rich people suck and so does racism.” This sentiment may gratify readers of the New York Times, but it can’t sustain a five-hour-plus miniseries. Wolfe’s book paints a rich and strange picture of American society threatened by rampant materialism and identitarianism. And in Stoicism, he even proposes a possible solution to some of these problems. Reading A Man in Full, you get the feeling that Wolfe cared deeply about America and spent a lot of time thinking about what was right and wrong with it. Watching A Man in Full, you get the feeling that David E. Kelley is a flippant TV writer with a shallow understanding of how America works.

Tom Wolfe was a conservative but that didn’t prevent him from writing critically about the harm that can be done when some fabulously wealthy business tycoon decides to put his own greed above the needs of the community at large. A Man In Full was published in 1998 but it is just as relevant today as it was 25 years ago. It has a lot to say about race, class, money in politics, sexual assault, and plenty of other contemporary hot-button topics. “There’s this stuff all the universities try to cram down the throats of their students about ‘diversity’ and ‘equality’ and ‘multiculturism,’” Inman Armholster complains at one point. “So they get brainwashed by all the stuff they’re hearing from teachers, from visiting lecturers, from the administration, from all the bullshit artists on television…”

Reasonable people can agree or disagree with some or all of the points that Wolfe is making, but David E. Kelley hasn’t done either. Instead, he has turned Wolfe’s story into a glossy and diverting but ultimately empty tale replete with progressive shibboleths. Wolfe seemed to believe that his country was losing its soul. A quarter of a century later, David E. Kelley’s misconceived adaptation proves that he was on to something.