Behind the Biennale: Sandra Gamarra Heshiki’s Ode to the Migrant Is an Exercise in Unlearning

By Agustín Pérez RubioOn the occasion of the 60th Venice Biennale — open now and running until 24 November 2024 — Something Curated continues its series, Behind the Biennale. Comprising a collection of essays from the curators of select national pavilions, the series offers first-hand perspectives on some of this year’s most exciting presentations.

Following Yvonne Billimore and Jussi Koitela’s essay on curating the Pavilion of Finland, curator Agustín Pérez Rubio elaborates on his experience working with Peruvian-Spanish artist Sandra Gamarra Heshiki on this year’s Spanish Pavilion. Pérez Rubio’s words have been translated from Spanish to English for Something Curated.

The presentation of Migrant Art Gallery, as a temporary institution made by Peruvian-Spanish artist Sandra Gamarra Heshiki – the first migrant artist in almost a century of Spanish presentation at the Venice Biennale – is the result of a long and rewarding process between artist and curator.

When Sandra was selected, a few voices from within Spain were critical about the idea of a non-Spanish born artist representing the country at Venice. This tied in with the themes of the work – that look closely at Spain’s colonial legacy – make this an important presentation for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It’s a chance to re-examine Spain’s colonial history and grapple with many topics that arise from this discourse.

Gamarra Heshiki’s pavilion is about turning the gaze on Spanish colonial rule and showcasing the voice of the migrant. This is a conversation that started between us several years ago, which materialised in the form of the Museum of Ostracism presented together with my dear co-curators of the 11th Berlin Biennale – Maria Berrios, Renata Cervetto and Lisette Lagnado – and at the exhibition Buen Gobierno (Good Governance) at the Sala de Alcalá in Madrid.

The first of the four rooms in this exhibition, titled Mirage Room, was in a way the seed for the Migrant Art Gallery project. What could be seen in these rooms, were the various ways that painting could act as a historical narrator, creditor of a supposed truth and how the discourse of the conquerors had prevailed over any other. So the artist made new versions of them from another much more critical, and truthful, narrative – based on how she understood the history between Peru and Spain, from the perspective of her native country.

Gamarra Heshiki’s work is based on appropriationism, on copying, as a way of embodying the imposition that the Spaniards made on the most skilled and dexterous natives. Now the artist subverts the action by doing the inverse, copying what Europe or in this case Spain has, to put up a mirror to its Eurocentric gaze. Through her work she reveals the Western museum to be a hegemonic institution, a narrator of grand narratives whose methods of presentation and representation have been accepted as “universal,” regardless of the origin of what is represented.

Migrant Art Gallery is conceived as the subversion of a historical Western pinacotheca, where the notion of migration is expanded upon. The hegemonic Western concept of the art gallery, which was also exported to the former colonies, is inverted by exposing a series of historically silenced narratives. The protagonists of these narratives are migrants, both human and nonhuman: people, plants, and raw materials often forced to make the journey back and forth.

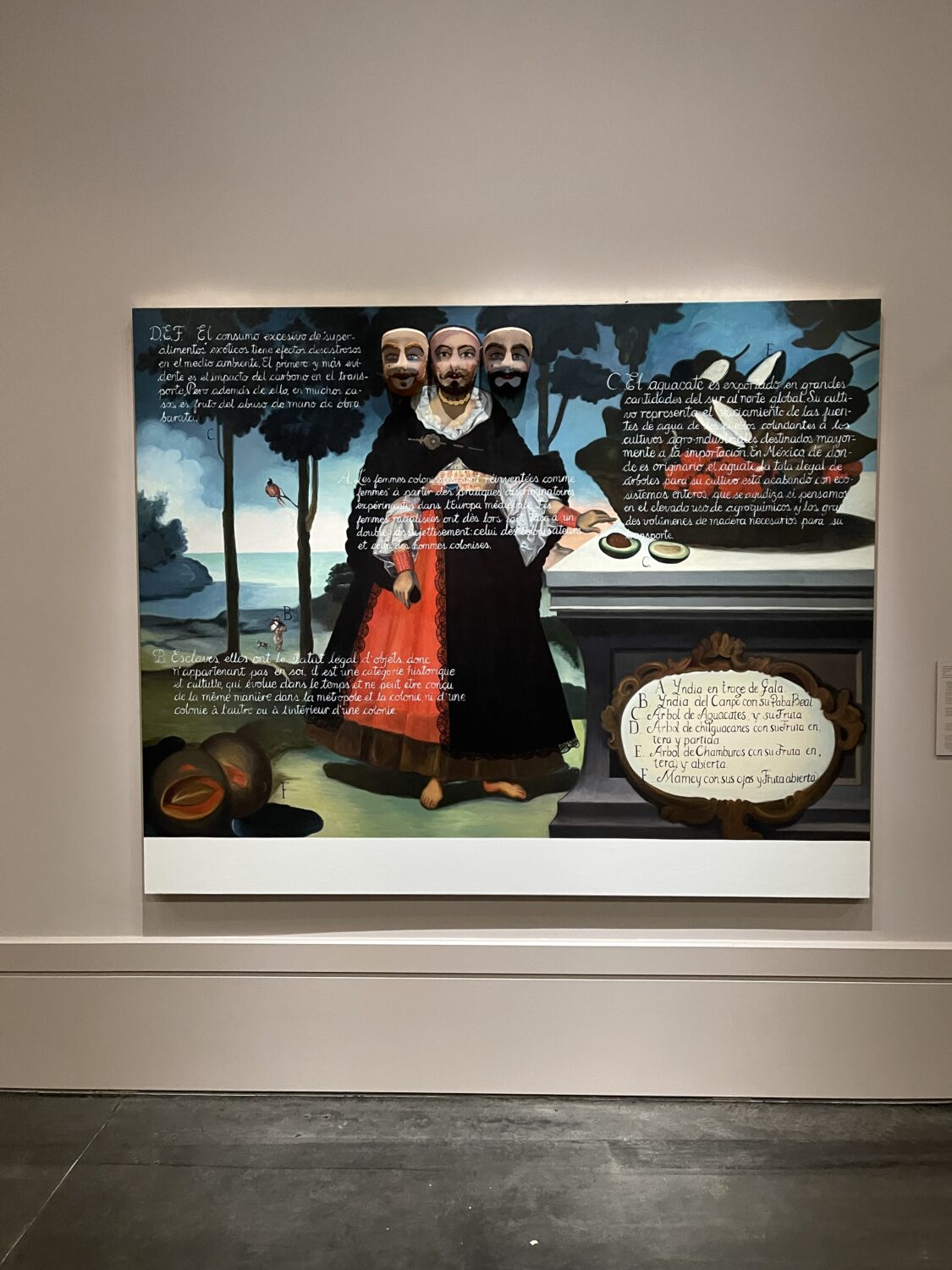

The new institution analyses the arts’ systemic structures through pictorial appropriations based on the artist’s research of more than 150 Spanish heritage paintings and objects in public collections and museums, from the Empire to the Enlightenment. Gamarra Heshiki’s revision interjects and shows the absence of decolonial narratives, exposing the bias with which colonisers and the oppressed have been represented in museums. Sociology, politics, art history, and biology are layered here to provide a reinterpretation in which historical consequences, often ignored, are linked to our contemporaneity.

The first five rooms of the pinacotheca use the different genres of classical painting – landscape, portraiture, still life, scientific illustration, and botany – viewing them as tools with political agendas that foster monolithic constructions of nation-states that are too often sustained by the destruction of other forms of social organisation. Migrant Art Gallery narrates the continuous cycle of construction and deterioration. It presents works – sketches, finished or in a state of permanent restoration – as a metaphor for institutional responsibilities toward a history in flux and a contemporary West inseparable from colonial wounds.

The first room, titled Virgin Land, deals with landscape paintings that belong to different Spanish museums and refer to the current Spanish territory, as well as the former colonies of Latin America, the Philippines and North Africa. Quotes from writers, ecofeminist thinkers or intellectuals are superimposed on each painting.

It is followed by the room titled Cabinet of Extinction, which links colonialism with extractivism by showing the “treasures” of European botanical expeditions during the 18th and 19th centuries. It includes work that are facsimiles of the illustrations from the “Royal Botanical Expedition to the Kingdom of New Granada,” including human hands as part of the same interdependent survival system.

The space entitled Cabinet of Illustrated Racism presents the way in which anthropology and science were used as tools of racial discrimination, and includes illustrations and objects labeled “scientific” at the time, to support the idea of classification and impose the Western will for hierarchical superiority over the Global South.

The room titled Mestiza Masks delves into the colonial practices of portraiture, which were conceived as time capsules that seek to immortalise political and social norms. Each work exposes the way in which societies accept or marginalise their subjects.

Finally, the Migrant Garden functions as a counternarrative to the museum: a place of symbolic restitution of unseen others, which seeks to dismantle the structures and representations that perpetuate colonialism’s hegemonic hierarchies. This space is inhabited by painted copies of twelve monuments, as well as representations of alien or invasive plants. Those represented here have made a symbolic journey, like alien plants, they have found soil to stay.

It presents the view that the alteration of ecosystems should be valued and measured from a perspective in which all species live harmoniously without hierarchies. This garden, at the same time, looks at the protocols around accessibility, diversity, and sustainability, proposing an institutionality that addresses contemporary contexts in relation to racism, sexism, migration, and extractivism.

As we used to say: “One day museums forgot they could be gardens.” They can be inclusive spaces where knowledge is shared. Migrant Garden is a space for calm, reading, for colouring, with seeds to take home, or for quiet and rest. The pavilion is designed to feel like an oasis, with the familiarity of the museum but acting as a place that puts human beings at the centre.

Feature image: Installation view of the Spanish Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale. Photo: Oak Taylor Smith