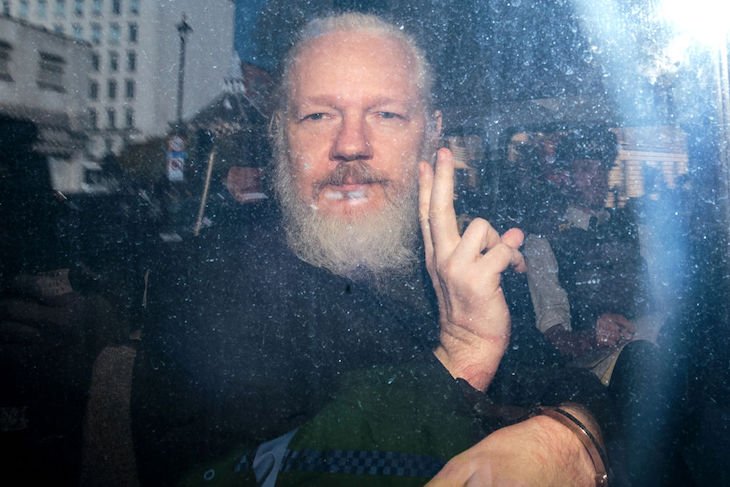

James Cleverly won’t be able to move the Julian Assange file out of his inbox quite yet after all. The High Court has allowed Assange to appeal once more against extradition to the US on the basis that no sufficient assurances have been received over his ability to rely on the First Amendment if tried there.

We don’t know what the result will be (today’s hearing merely gave permission to appeal, with no guarantee as to its outcome). Nevertheless, we should still think twice before we hope that the appeal will ultimately be dismissed, thus allowing the final removal of someone who has been a thorn in the UK authorities’ side for nearly 15 years.

This is Assange’s second brush with extradition law. In 2012, he stymied a largely ordinary rendition to Sweden on charges of sexual assault and rape (which he denies) by remaining holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy for seven years, until the Swedish government lost interest. The present request by the US, the subject of today’s hearing, was on entirely different charges, namely conspiracy to obtain and disclose US defence information contrary to the US Espionage Act, arising out of the Chelsea Manning leaks which he collaborated with the Guardian in publicising, and also in large measure revealed in Wikileaks, in 2010. Assange denies any wrongdoing.

In law there is no doubt that, subject to any quibbles over assurances from Washington, this is an entirely regular request from the State Department. There are nevertheless several reasons that should give us pause about allowing extradition for state crimes of this kind.

One is the effect on press freedom. True, technically Assange is alleged to have committed an offence in the US by suborning people there to provide him with secret information. But the essence of Washington’s complaint is that Assange, a journalist in England with no connection with the US, has published, in England, material classified in the US that is contrary to US espionage law. Admittedly in this case the leaks could hurt us too, since we make much common cause in defence with the US. But this will not always be so. Imagine a request from, say, South Africa, India, or Brazil, alleging abstraction of classified information there on the orders of a UK columnist and its publication here. The same would apply. Unless the journalist can show a likelihood of prejudice or oppression if sent for trial, extradited he must be. In short, the vital ability of the press in Britain to publish what it likes about foreign regimes provided it obeys our law, whatever their own law may say, is now seriously in doubt.

The second reason is more general. Fifty years ago, our law did not only bar extradition of those likely to face persecution. It also, broadly, prevented extradition for any non-terrorist offence of a ‘political character’, something that automatically excluded matters such as espionage and other anti-state offences. Unfortunately, this principle was abandoned as regards European states with the adoption of the European Arrest Warrant (something which, three years ago, nearly led to Clara Ponsati, a vocal Catalonian separatist who later took up a teaching job in Scotland, being forcibly bundled onto a plane to Madrid to face criminal charges of subversion before a Spanish court). Later in 2003 the Labour government suppressed the principle altogether in a new Extradition Act.

This is unfortunate. An attractive feature of Britain was once a libertarian insistence that, however friendly its relations with another state, friendship did not extend to helping that state with its dirty work in rounding up subversives. But today libertarianism of that kind is unfashionable. Even if you have fallen foul of your government, you are in the UK’s eyes just like any other criminal: if your government makes a request, even for a state offence, the UK will happily hand you over unless you can show that you are likely somehow to receive unfair treatment when sent back to face it: something that can be easier said than done.

And this raises a third point. Whatever you may think of asylum claims in general, the extradition rules that the courts now have to apply subvert what was once a proud British tradition. In the nineteenth century, our political life was much enriched by the fact that critics of foreign governments were allowed, assuming they were reasonably well-behaved, to carry on their campaigns here. Not only did the law protect them from rendition for offences like sedition; in addition, all extradition requests had to be approved by the Home Secretary, who if he felt that the foreign government was overstepping the mark, could simply refuse to give effect to them. This too has unfortunately gone. The entire process is now legalistic: if the legal requirements for extradition are satisfied, then whatever the Home Secretary’s view, he is bound by law to go ahead with the extradition.

In short, Britain has now apparently bound itself in a tangled web of law to abandon its tradition of harbouring dissidents, and has to hand over someone in Julian Assange’s position, whatever electors and their representatives think of the case and whatever the knock-on effects on the freedom of the press. We now need a movement to draw attention to this. There is much to be said for Rishi Sunak setting up a body to revisit our extradition law to make sure this kind of thing does not happen in future.

Comments

Comments will appear under your real name unless you enter a display name in your account area. Further information can be found in our terms of use.