Executive Summary

A growing chasm between the education system and labor markets in the U.S. is making it harder for employers to find and retain qualified talent, and it also is stunting the career and education options available for Americans without a college degree. Minor tweaks will not address the scale of the chasm. If the country seeks to activate more of its homegrown talent to continue innovating and competing on a global scale, it will need an all-hands-on-deck approach to be successful. Incentivizing and empowering employers to be more active in the education system is a critical first step toward achieving quality work-based learning at the necessary scale. The U.S. must re-engineer its systems so that more employers are incentivized and empowered to do this.

This report maps out a new role for employers in the U.S. education and training systems. It starts from the employer perspective to identify enabling policies and infrastructure. We draw from promising practices in several states and countries that are leading the way in aligning education and employment systems. Brookings Metro has convened teams of leaders in education, commerce, economic development, and workforce development for over two years in three states—Alabama, Indiana, and Colorado—to understand their work on scaling earn-and-learn opportunities. Insights from this community of practice have informed this report as well.

We envision an education system that employers will partner more closely with, instead of distancing themselves from. With tight labor markets and changing skill needs, many employers are already rethinking their approach to human resources (HR), internal staff development, talent sourcing, and the time horizons for these interventions. We argue that opportunities to learn on-the-job and to have that learning recognized for credit and credentialing—whether through an entry-level program like apprenticeships or professional development to support career advancement—must be scaled to meet the demands of today’s labor market. To do this in a federated system like the U.S., states are well-positioned to take the lead in building the infrastructure and policies that would enable this transformation to a system with multiple pathways, in which employers have an active and ongoing responsibility to design, deliver, and assess the training that happens in their own workplaces.

Today's context

As baby boomers retire, digitalization expands, wages rise, and the job market remains strong, American employers are feeling a serious pinch for talent. For example, Cyberseek, a project funded by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, notes, “From February 2023 through January 2024, there were only 82 cybersecurity workers available for every 100 cybersecurity jobs demanded by employers.” Given the acute nature of the problem, near-term solutions such as removing degree requirements for jobs and instead hiring people based on their skills are gaining momentum. Not surprisingly, as employers rely less exclusively on traditional college degrees for hiring, more young Americans question whether a college degree is still worth it. Both employers and students see a gaping disconnect between the outcomes of the education and training provided in the U.S. and the types of skills and experience that employers value.

Although skills-based hiring is an important step in creating greater access to high-quality jobs, it will not be enough on its own to create robust, navigable pathways into the jobs of tomorrow. Without an abundance of choices for advancement and reskilling, skills-based hiring may lead to a dead end for many workers. What’s more, if employers continue to distance themselves from formal education systems, they risk creating a longer-term problem downstream in their talent pipeline. The pace of change in technology, systems, and culture will likely require more frequent reskilling over an employee’s career, not less. Demand for emerging higher-level digital skills, problem-solving skills, and advanced education or training is surging as new technologies like artificial intelligence deploy into everyone’s job across industries and occupations, up and down the organizational chart. Employers are arriving at a critical juncture: help rebuild the system now or risk it becoming completely irrelevant to their needs in the very near future.

How did the US get here?

Work-based learning was not always relegated to second-class status in America. Apprenticeships, for example, played a pivotal role in the country’s early days. George Washington, Ben Franklin, and Paul Revere were all apprentices in their day. However, the law governing the apprenticeship system has not been updated since 1937, even though the nature of the economy has changed dramatically since that time. There are several structural challenges with the setup of apprenticeships in the U.S. that limit their scale and scope, especially in modern, fast-growing industries such as healthcare, technology, and business services. For example, the fact that registered apprenticeships in the U.S. operate outside the education system and do not culminate in a formal degree in the education system keeps this pathway marginalized and harder to combine with formal education. Students and parents often do not know about these options for professional training, or they have the misconception that apprenticeships are for low-achieving students or students who have zero interest in going to college.

This marginalization and stigmatization of vocational and technical education is embedded in long histories of racialized tracking in the U.S., where Black and immigrant students were frequently directed away from college preparatory curriculum and into vocational programs with the inability to switch paths later on if they decided they wanted to go to college. For this reason, apprenticeships are still widely considered to be a lower-status alternative to a college degree rather than an option that can improve a student’s selection of a degree program later on by exposing them to direct work experience or even lead directly to a degree itself (in the case of a degree apprenticeship).

In an attempt to right the wrongs of racialized tracking, U.S. policymakers have pivoted to a “college-for-all” approach to education, promoting a college degree as the sole path to success. At the same time, employers in the U.S. have tended to focus on more short-term goals such as filling immediate job openings rather than on long-term investments in staff development, under pressures to prioritize shareholder returns over other competing priorities. Learners, therefore, have been encouraged to pursue the slow, costly path of degree-bearing educational pathways, while employers have looked for cheaper, faster solutions to human capital shortages. On one side of the equation, the formal higher education system in the U.S. has doubled down on classroom-based education, providing very few students with substantial hands-on learning in the workplace. On the other side, employers have found themselves needing to invest heavily in training recent college graduates in hands-on, industry-oriented skills even though they already pay them a professional-level wage (whereas an apprentice would receive a professional-level wage after completion of training).

Keeping work-based learning—whether that means an apprenticeship or staff development training—small in scale and focused on a limited number of industries is a significant missed opportunity to meet the needs of a growing number of employers and learners.

To address this gap, a chaotic landscape of post-secondary credentials has developed outside of the formal higher education system to try to meet employer demand for training and talent. The U.S. has more than 1 million certificates, badges, and other credentials that are frequently lumped together under the broad category of “non-degree” or “non-credit” programs. Although these nonformal programs might be organized and have learning objectives, employers often struggle to make sense of how qualified someone is because the number of programs is overwhelming, they are not tied to a specific education level, they are inconsistent from one place to another, and there is limited information available about program quality.

Today, employers report a persistent struggle to find the talent they need to innovate and compete, and their recruitment and staff turnover costs are escalating in the post-pandemic era as baby boomers leave the workforce and cultural attitudes about work and education evolve. Workers and learners, meanwhile, frequently find themselves stuck in low-wage jobs with few opportunities for career advancement or higher education, unless they agree to take on the financial burden of formal higher education and live on a limited income for an extended period of time.

Keeping work-based learning—whether that means an apprenticeship or staff development training—small in scale and focused on a limited number of industries is a significant missed opportunity to meet the needs of a growing number of employers and learners. We propose building new infrastructure to incentivize employers to play a more active role in hands-on, professional learning pathways. The goals of this new infrastructure are to increase efficiency, transparency, and clarity about employer roles and responsibilities in talent development.

Building the infrastructure employers need to scale work-based learning

Businesses rely on dependable infrastructure to grow and thrive. Without physical infrastructure like roads and bridges, technological infrastructure like the Internet, and a basic infrastructure for the safety and care of employees, no business would be able to achieve scale. If the key problem with current attempts at earn-and-learn workforce development interventions is scalability, we must examine whether the underlying infrastructure is high-quality, complete, consistent, and accessible enough to allow employers to operate at scale. What “roads and bridges” is the U.S. missing in its attempt to help businesses find, train, and promote unemployed and under-employed Americans for open positions in high-quality jobs today?

In the following sections, we highlight the common, but frustrating, experiences employers have in seeking to scale their earn-and-learn interventions, like apprenticeships. Each highlights systemic gaps or inefficiencies that can hinder employers’ ability to continue and/or expand their participation in talent development efforts. We look at the cost of inaction around these challenges and share some potential solutions informed by other developed countries’ systems, as well as by some emerging efforts in a handful of U.S. states.

Given that the U.S. has a decentralized, federated governance model for education (including higher education), states have more levers of control over education and training than the federal government does. But the federal government still has an important role to play, such as supporting common definitions across states to create a shared language, as well as directing major federal investments in certain areas and industries, such as unprecedented investments in infrastructure, that can create more opportunities to scale work-based learning. State and local leaders can leverage federal policies, infrastructure, and investments to guide their decisions about how to prioritize efforts to scale earn-and-learn opportunities.

Below, we will look at how making space for employers and giving them a role in the redesign of the system might be accomplished by prioritizing efficiency, transparency, and governance.

- Efficiency: This means allowing employers to collectively name and define key occupations and occupational pathways in which individuals can reliably leverage work-based learning to acquire a significant percentage of the knowledge and abilities necessary to perform proficiently in a particular role. Once these key hands-on learning pathways are identified and agreed upon at the occupational level, employers must then further name and define the key skills and learning milestones within them.

- Transparency: This entails bundling the agreed-upon skills and occupations into easily discernable pathways for learners within the formal education system, or mapping these pathways alongside traditional classroom-based pathways. This helps learners and employers alike make sense of qualifications and credentials by classifying them according to how advanced they are (level), whether the learning is more hands-on or theoretical in nature (type), and how they fit into a broader learning progression or career switch.

- Governance: This requires giving formal authority to employers in terms of the oversight, maintenance, and refinement of the professional and work-based learning parts of the system. It also means ensuring their continued participation in defining quality in individual programs and developing assessments and credentials to test and validate learning across various contexts (by employer, geography, industry, and other factors) over time.

The overarching goal is to expand the accessibility of high-quality learning environments where Americans can prepare for modern careers; inviting employers to become active participants in the U.S. educational systems is a key way to advance this goal. Even though college degrees remain the north star of the formal education system in the U.S., the system leaves roughly two-thirds of Americans without a bachelor’s degree. If the U.S. hopes to compete globally, the system will have to expand its options and reform its approaches to accommodate more and different types of learning to make sure that all learners can succeed in the labor market of the future.

As employers step up to take on some of that responsibility, the education system must give them the authority to inform and assess their respective domains of expertise. This more balanced relationship, supported by an infrastructure that ensures high-quality, consistent implementation, will serve both learners and employers. In fact, increasing linkage between employers and education systems, making it easy for employers to participate, targeting the right occupations, designing the duration and scope of programs, increasing time spent in the workplace, and other factors can all be leveraged to increase an employer’s return on investment (ROI) from work-based learning models such as apprenticeships, while simultaneously bolstering learners’ success on the broader labor market.

Having work-based learning options in the formal education system is more effective than relying on classroom education alone

Outside the U.S., work-based learning pathways are commonly referred to as vocational education and training (VET) programs. There are two types of VET programs: school-based and dual VET. School-based VET programs mean that learning happens in the classroom (and that less than 25 percent of participants’ time is spent learning in a work setting). Dual VET programs mean that students split their time between the classroom and the workplace, with at least 25 percent of their time at work, such as in an apprenticeship program. Research shows that graduates of dual VET programs consistently have better labor market outcomes than those of school-based VET programs. Countries with a higher share of learners in dual VET programs have lower youth unemployment rates than countries with more school-based VET efforts. Under these definitions, most Career and Technical Education (CTE) programs in the U.S. are not VET because they do not lead to a formal, occupation-specific qualification. CTE would also typically be considered school-based VET, because work-based learning makes up less than 25 percent of participants’ time.

Making it easier and more efficient for employers to get in the education game

The employer view: inconsistency and inefficiency discourages the creation and replication of apprenticeship programs

As apprenticeships have expanded in the U.S., it has become clearer that the country’s education and training systems are not designed to recognize and value learning that takes place outside of traditional classrooms. Employers and intermediaries trying to create apprenticeships encounter friction and unnecessary red tape. Registering (which is the process of formally establishing an apprenticeship program that is recognized by the U.S. Department of Labor) is typically handled on an individual basis for each employer, particularly for emerging industries and occupations, and the process offers a compelling case for change. Registration processes often have legacy requirements that are ill-suited for the rapid evolution of many occupations; for example, requiring an occupational safety and health certification for office jobs—even remote ones. The administrative challenges and duplicative processes across companies and industries are inefficient and cause unnecessary delays in sectors where the need for apprenticeships is clear. As a case study, the registered apprenticeship system illustrates some of the pain points that employers encounter because of the absence of formal organization and coordinated systems. Frequent challenges include:

- Inconsistent or unknown starting points for building programs for new occupations and pathways;

- Slow processing of individual programs’ registration applications, at both the state and federal levels;

- The sheer number of other institutions that employers must coordinate with to offer an apprenticeship (such as schools, community colleges, the government, intermediaries, and others);

- A confusing and unregulated landscape of related classroom-based instruction that varies widely in content and quality;

- A lack of standardized metrics that employers can use to make decisions about the quality and effectiveness of potential partners; and

- The absence of a common data or information platform that communicates what programs exist, how they work, whether they are effective, and how employers can use them.

These burdens discourage many employers from establishing registered apprenticeship programs, but they have a disproportionately negative impact on small- and medium-sized employers, who have limited resources themselves. These inefficiencies cascade not only across employers but also across state agencies and across state lines. For example, even if a successful apprenticeship program in cybersecurity sought to scale up its implementation and had enlisted 100 employers who wanted to do something similar, the state agencies responsible for registering programs would still need to process all 100 registrations separately. Each of those 100 employers are then incentivized to create their own program from scratch, rather than being guided to participate in an already-vetted learning curricula that they can lightly adapt for their own workplace.

The solution: employers can collaborate on occupational frameworks and curricula to share for easier adoption and adaptation

If the goal is to ensure that highly motivated employers like Martin can get started quickly and focus their efforts on training apprentices rather than navigating state bureaucracy and designing training curricula from scratch, then U.S. state and local leaders should focus reform efforts on ways to shift from one-off programs for each employer to a cohesive system that makes it easy for them to participate in and adapt an existing training curricula for a given occupation. We propose three mechanisms for achieving more efficiency:

The aforementioned interventions will provide employers a more streamlined way to participate in high-quality work-based learning programs without having to create them from scratch each time and get them separately approved. These work-based learning infrastructure at their interventions would also reduce the burden on employers to find and vet an education provider or develop their own training curricula in-house by engaging directly with the educational system, while the governance of the system (see section 3) can protect their ability to customize curricula where necessary and update it periodically. Leveraging education institutions in this manner can substantially reduce the costs for employers, making it viable for more employers to invest in work-based learning solutions like apprenticeships.

In other countries, when intermediaries engage employers to design and update professional education and training programs to ensure they are high-quality, this happens on a national or statewide scale and includes secondary and postsecondary levels. For example in countries like Australia, Denmark, Singapore, and Switzerland, curricula for work-based learning and professional training—the set of competencies that industry and educators agree on for each occupation—are set at the national level. Germany uses state-level curricula, as does Canada (with the exception of Red Seal apprenticeships). In all of these cases, when the effort, time, and resources to develop industry-driven occupational curricula are coordinated across institutions and geographies, more students, providers, and employers can benefit from that work. This coordination not only unlocks the scalability of high-quality programs within particular pathways or occupations, but it also increases the diversity of choices available by offering a variety of pathways and occupations. For example, well-established systems like Denmark and Switzerland offer between 100 and 250 occupational pathways for their learners.

By contrast, in the U.S., each employer sponsor submits its own bespoke program to be registered one-by-one, and related instruction providers duplicate efforts to design and approve curricula for similar programs. This is why it is a lot harder in the U.S. to achieve scale quickly, options are limited, quality assurance is unclear, and awareness of any given program outside of the building trades tends to be very low.

Making candidates’ qualifications clearer and more transparent

The employer view: confusing and risky variation in non-degree credentials artificially limits the talent pool and increases costs

Employers in many industry sectors are struggling to find qualified candidates for open positions. However, the Wild West landscape of nonformal credentials can mean that employers overlook candidates who may in fact be well qualified. Like Breanna, they often fall back on using the attainment of a college degree as a proxy assessment for skill because it is efficient and less risky than trying to assess the value of unfamiliar credentials and certificates. This misuse of the degree to screen for candidates means that employers can end up paying more for a candidate who has a degree but not the specific skills required for the particular occupation, even when they don’t end up paying more to poach an already-experienced worker. Neither strategy solves the root problem, and both actually increase the cost to hire. The status quo results in unfavorable options:

- Workers with skills but no college degree are hard to assess as job candidates because the quality of their credentials is difficult to discern;

- Learners who have invested time and effort into a non-credit credential or certificate cannot effectively signal their skills to employers, and education providers’ products can be prone to undervaluation in the labor market if employers fail to recognize or understand their value;

- Workers with a college degree but little work experience need significant hands-on, industry-specific training, even after they are hired at the higher level of wage/salary that their degree commands; and

- Poaching experienced workers becomes more costly as the pool of qualified workers gets smaller over time as retirements occur with more frequency, leaving smaller demographic cohorts to fill open positions.

In the U.S., the high cost of college and other factors prevent many talented individuals from completing a degree. In fact, according to the U.S. Census, more than 119 million Americans over age 25 (53 percent) have a high school diploma or more in 2021, but no bachelor’s degree (Source: Calculated by authors from Current Population Survey, Table 2. Educational Attainment of the Population 25 Years and Over, by Selected Characteristics: 2021. A sum of the population with high school diploma, some college no degree, and associate’s degree). The pool of qualified talent, therefore, becomes smaller and less diverse when employers impose degree requirements. Even among individuals who do have relevant degrees, employers frequently report that the skills they learn in school, college, or training programs are not relevant to actual industry needs. And when a school, college, or training provider does deliver all the right skills, only employers in the local area or those that participate in or hire from the program are likely to be aware of that. The result is that after finding and hiring someone at the wage of a fully skilled worker, employers invest again in training on top of lost productivity while the new employee gets up to speed. In the U.S., new employees often take a full year to reach full productivity.

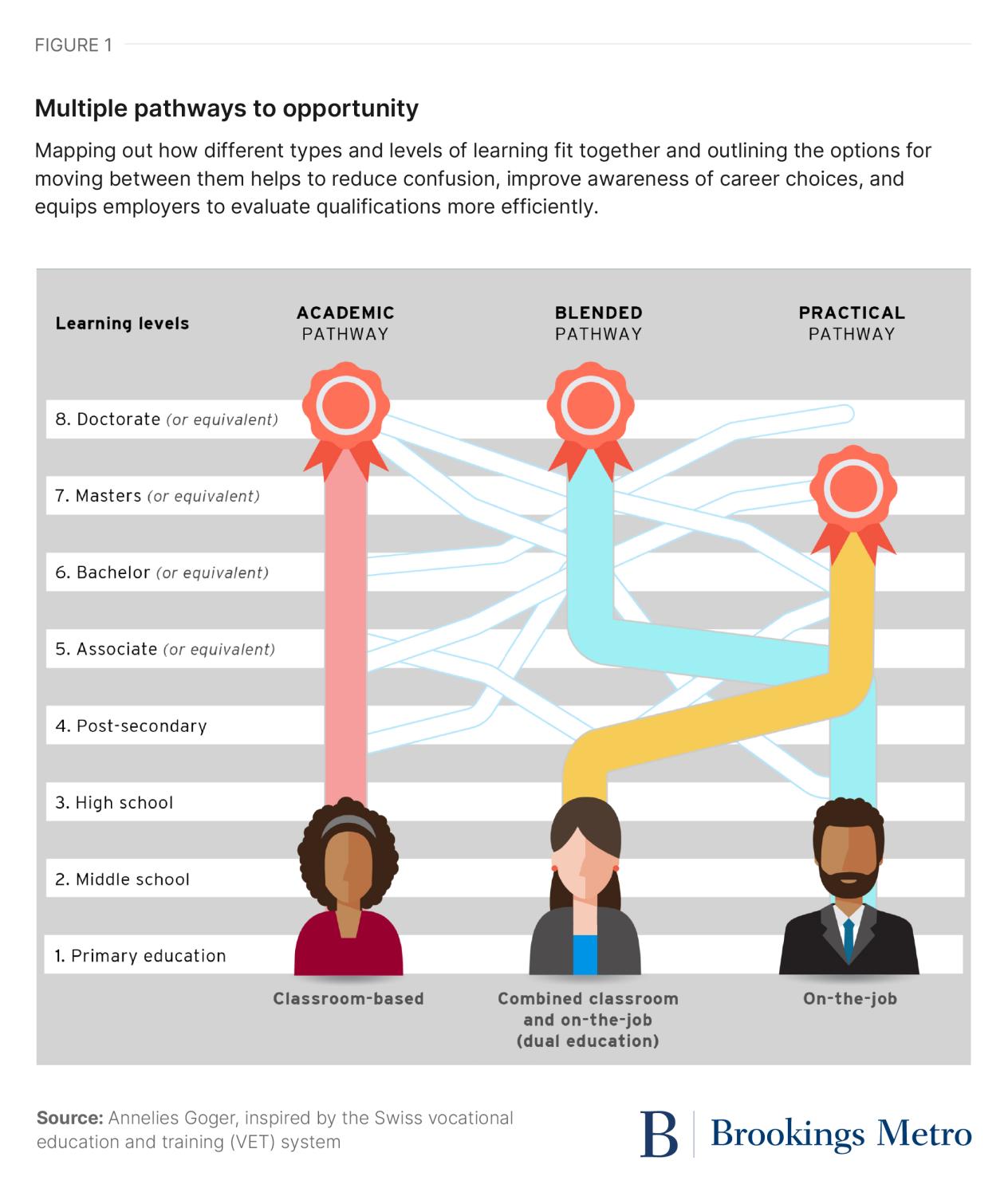

The solution: recognize and organize professional learning and training within the education system

Employers need a solution that allows them to quickly identify which candidates have relevant, measurable qualifications to meet their workforce needs. As we have described above, the process for organizing this expanding system to make it more transparent relies on a shared intellectual infrastructure for the domain of hands-on, skills-based training and education, just as there is a shared intellectual infrastructure for classroom-based education. This shared agreement allows for scale across contexts. In other words, if the learning content of an English 101 course is largely recognizable across learning environments, a robotics technician 101 course should be just as recognizable, even if that curriculum is carried out at a manufacturing workplace rather than in a classroom. Next, to integrate those pathways into the formal system also requires any program or set of courses and/or learning experiences to be sorted into various levels, according to their duration and difficulty. Levels are also necessary to establish equivalency between programs that intentionally serve different purposes. The figure below shows how each pathway has clear progressions from basic to advanced skills and knowledge, how they are differentiated between more theoretical knowledge and more applied, and how one can either advance or switch pathways with clarity about what is necessary to do that.

Most other countries have education systems that include both academic pathways and practical pathways that equip workers with professional certifications and/or work-based learning, with the latter typically referred to as professional or vocational education and training (known by the acronyms PET or VET). Importantly, these VET and PET pathways include certifications at levels from the basic high-school level to high-level professional qualifications, such as those for becoming a certified financial analyst—a skilled occupation in the investment banking and finance sector.

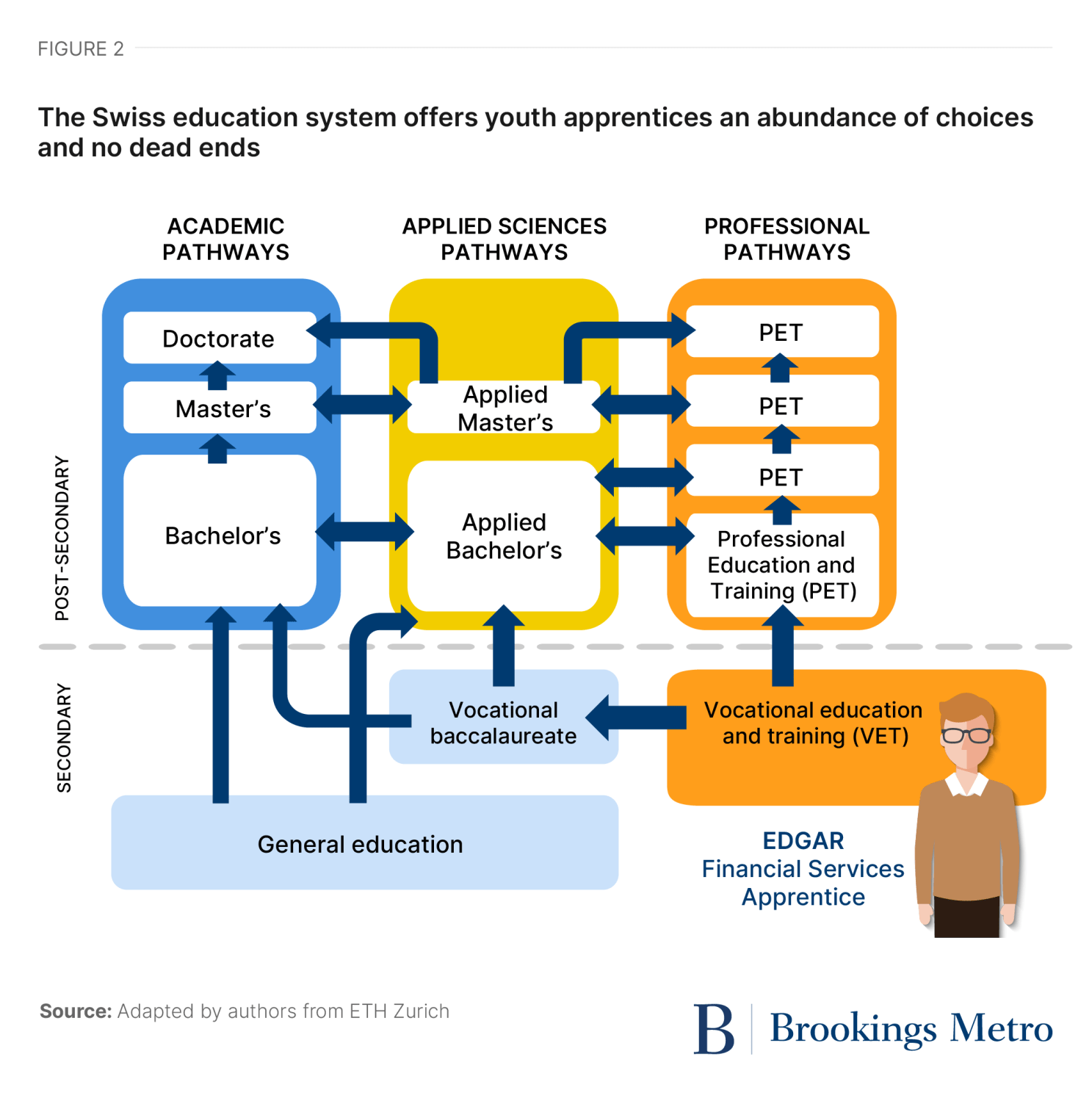

In Switzerland, for example, professional learning pathways are particularly well developed as part of a formal, validated, and trusted comprehensive system of education that serves the entire labor market, rather than just a handful of lower-level and/or lower-paying pathways. Employer satisfaction with the quality of these practical, work-based learning options is evidenced by their heavy engagement in the system and positive returns on investment before the end of apprenticeship training programs. Integrating academic and practical pathways into a cohesive, comprehensive educational system—rather than creating separate tracks with differing endpoints—is critical for ensuring that individuals remain connected to subsequent, upwardly mobile steps in their education and training at each juncture. Changing paths in those systems is relatively seamless, given the clear and consistent organization of different types of learning and programs. The expanded set of fields, pathways, and occupations served by such a system also produces high levels of innovation and larger pools of qualified workers with a more diverse range of skills and experience. Figure 2 below shows how a financial analyst apprentice (at the equivalent of high school level in the U.S.) has many options to switch pathways or occupations at any stage, as well as clarity about how to progress to a more advanced level in each pathway.

As the U.S. builds the intellectual infrastructure to differentiate between types and levels of learning, employers and learners need to be able to navigate and differentiate between them. Around the world, many countries use a national qualifications framework (NQF) that specifies types and levels of learning, equivalencies across different pathways, and the process for moving from level to level within or across pathways. An NQF provides a unifying policy framework for different types of learning across various funding streams and programs, and it helps individual players see and understand their role in the larger system. These frameworks operate like a map that helps employers and individuals alike understand where they are and what is needed to get to the next destination, but, just as a map can’t actually transport people, a framework can’t deliver skills. High-quality programs with relevant curricula, the right delivery mechanisms (see section 1) and good governance (see section 3) are still necessary. And just like a map does not need to show every tree to be useful, not all learning needs to be formalized into a framework—there is still room for non-formal and informal learning at various junctures.

A qualifications framework for the U.S. education system would enable employers to differentiate between someone with entry-level skills versus more advanced skills and to identify candidates who have more hands-on learning experience than theoretical knowledge. Being able to compare theoretical, classroom-based learning at one level to applied, work-based learning at the same level also would create equivalency between the value of an academic degree and vocational or professional programs comprised of experiential, hands-on learning. As such a system matured and as programs and their outcomes were measured, evaluated, and refined, this progress would help promote equivalency in value on the labor market—not to mention equivalency in dignity and respect in the broader culture. Over time, vocational and professional programs that met the definition for a given level would be regarded just as favorably as traditional markers of achievement in learning such as associate’s, bachelor’s, or master’s degrees.

Given the federated setup of education policy and practice in the U.S., it may make sense for the U.S. to approach an NQF in a way that resembles the regional qualifications frameworks in other world regions, such as the European Qualifications Framework. This regional framework is a translation tool that aims to give individuals more transparency about how to ensure that their credentials and qualifications will be recognized in another European country, promoting mobility and lifelong learning in the region. Regional qualifications frameworks are high-level enough to enable member countries the autonomy they need over their own education systems, but they also provide a way to harmonize and coordinate across countries, such as by establishing shared definitions and using the same learning levels and types.

The employer view: no incentives for coordination and participation

In the U.S., employers play a relatively passive role in education and training, and while they are sometimes invited to share their input on training curricula through advisory groups, they do not have formal authority to define, approve, or assess skills and competencies for a program (nor do they have a designated representative body with that role). There are few incentives for them to self-organize or to actively engage with community partners beyond an advisory capacity until their hiring and training costs reach a crisis level.

When employers do try to engage to ensure that employment and training programs are aligned with their needs, they frequently report the following challenges:

- Multiple similar, and often overlapping, requests from different institutions for input on program design or content, without compensation for time or effort;

- A lack of clarity about the employer’s role, or having varying role definitions, across the various programs or interventions; and

- Untested or unclear outcomes and a lack of consistent methods for tracking a working learner’s progress toward those outcomes, resulting in an inability to measure a return on employers’ investment and engagement.

The current U.S. education system affords little opportunity for any player outside the formal education system to shape curricula and improve quality. This erects artificial barriers between learning and working and between education (for academic credit) and training (not for credit). These barriers add to the friction people experience when they transition from school to a career or from work to higher education, and this contributes to poor hiring and training outcomes for employers. When educators alone have the authority to decide how programs are designed and run, employers have little incentive to spend much time collecting data and analyzing it so as to refine the very programs that rely on their participation to exist. These disincentives lead to a downward spiral of passive, reactive engagement with education system, as employers distance themselves from the process of learning, see declining returns on training investments, and see themselves mainly as consumers of the system’s product (talent) rather than co-producers. And this state of affairs makes it easier for employers to blame educators if the skills and curricula they teach are outmoded or irrelevant, rather than having employers occupy a defined role with clear responsibilities in that process and being held accountable themselves as well.

Further, when cultural perceptions wrongly indicate that hands-on, work-based programs lie outside of the formal education system, and outside of the core mandate of employers, these programs become second-tier, low-prestige (unrecognized and uncompensated) efforts that are taken on out of obligation or goodwill, rather than by virtue of their economic, social, or educational value.

The solution: reconfigure employer-educator relationships to channel employer engagement more effectively

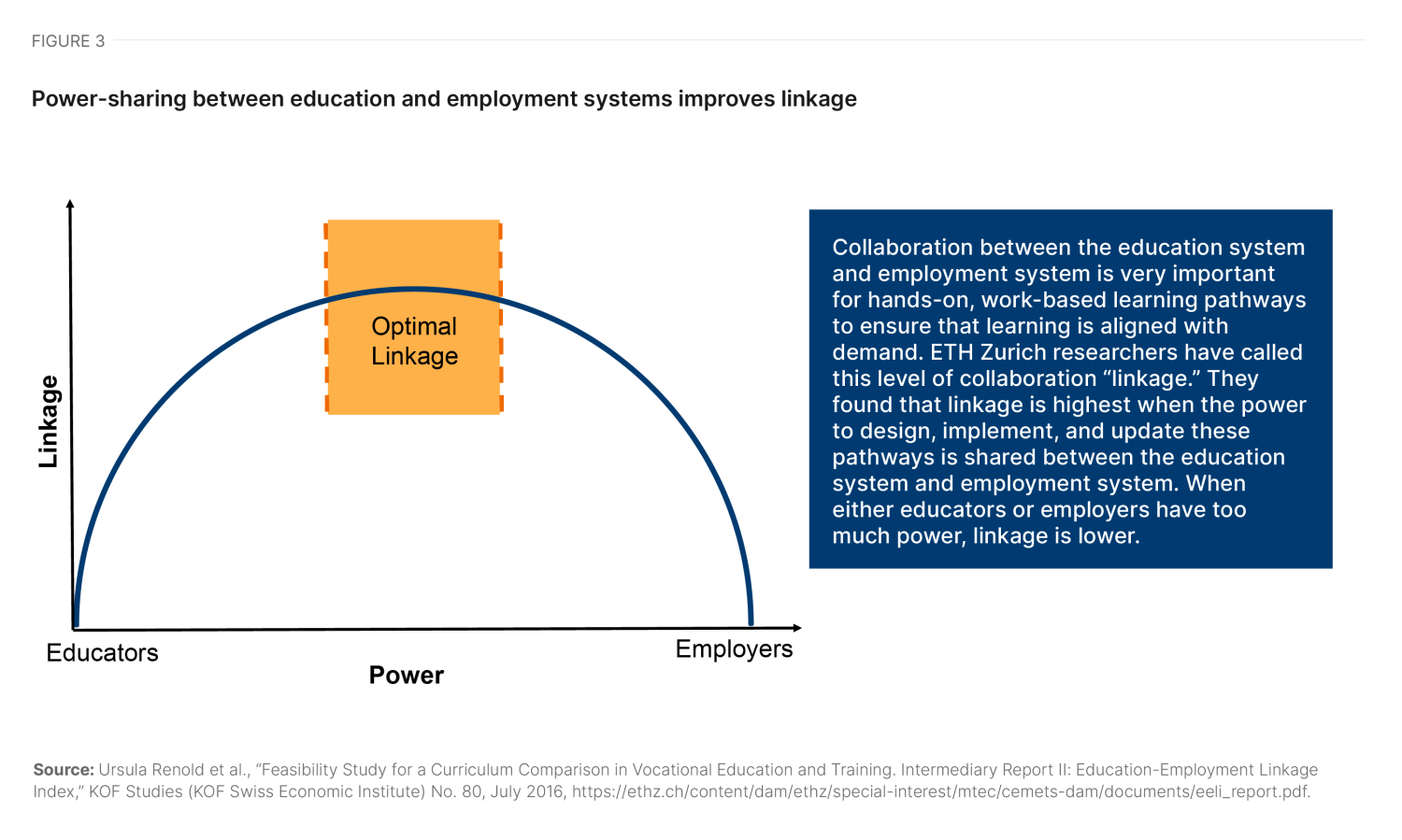

To enable and incentivize employers to engage more actively in talent development, state policymakers can focus on interventions that empower employers to shape professional education and training pathways to keep them relevant and high quality. The goal is not to shift power to employers alone, but to achieve an optimal state of power sharing between employers and educators so that they both have a defined role and responsibility in the system (see figure 3).

An initiative to improve linkage between the education system and employers would empower employers to work alongside educators to shape hands-on learning pathways, including the following key elements: an organizational body, a clear role for employers in the education system, and shared metrics.

- An organizational body: As things stand now, employers have little incentive to organize unless they have a clear role and can trust that their efforts will have an impact. Intermediaries and education and training providers often express concern about giving employers, who may not agree with one another, significant decision-making power. However, employers need a reason to invest heavily in organizing and identifying their needs and priorities. When employers are given real power, they have an incentive to speak in a unified voice about shared skill needs. Granting a sectoral or occupational governance body the authority to co-lead vocational and professional programs alongside public-sector actors like workforce boards, Career and Technical Education programs, and apprenticeship offices would likely generate more meaningful, sustainable engagement.

By law, employer associations in Switzerland must be equal partners in key decisions about the high-school-level VET program in their respective occupation(s). Decisions like curricula content, how exams work, how much work-based learning time is required, and when curricula are updated are not exclusively up to public-sector authorities or the education system. This approach is common in programs throughout Europe designed to promote linkage between higher education and employment. It is not necessary in academic programs, so having a differentiated role for employers in different types of learning is important. The role of employers also varies by level: employer associations have almost complete power over postsecondary PET, compared to co-leadership of high-school-level VET.

- A clear role in the education system for employers that plays to their strengths: Employers’ lack of power to shape certain aspects of education and training programs increases the costs of training due to factors like out-of-date content, inadequate work-based learning, or poorly designed employer-trainee matching processes. These challenges also decrease the value of training programs because of the misalignment between what such programs prepare people for and what they need. State policymakers can combat this by emphasizing employer power in the areas that matter most, such as their role in defining competencies, triggering revisions and updates, assessing and validating skill attainment, and providing structured work-based training.

Research shows that the most important areas for employers to exercise power are in delivering work-based learning, designing curricula content, defining how skills are recognized, and triggering curricula updates. Productive employer engagement requires that employers are co-leaders in these areas. Other forms of engagement—for example, advisory councils without decision-making power—are not as effective.

- Shared metrics to assess outcomes: Creating guidelines about metrics to enable employers to track and analyze their returns on investment in education and training, as well as data about learning and employment outcomes, is necessary to inform relevant decision-making. This requires both descriptive and causal research to track both outcomes and impact, which means funding is required not just for standard monitoring and evaluation but also for university-based research.

On the whole, the Swiss labor market is, like the American labor market—highly market-driven. Unlike other European countries’ training programs, Swiss training companies can’t count on their apprentices to stay after they have completed their VET programs. That means most training companies have to earn back (or exceed) their training investments by the end of a participant’s apprenticeship. If not, the program isn’t sustainable and the companies would stop training. Federally funded research tracks employers’ ROI for training, and key decisions are made based on the data. For example, if employers in one occupation were losing money, their employer association would advocate for—and probably get—more work-based learning time or a longer program duration so apprentices could be more productive. The association might also argue for a reduction in what it considers less-relevant competencies to make room for these changes.

Taken together, these components help address the simultaneous problems of employers feeling pestered and ineffective at shaping training curricula. Policymakers who want to stop this cycle have to start by giving employers power over key decisions like curricula content and updating and giving employers the authority to deliver parts of the curricula through work-based learning.

Summary and recommendations

Tight labor markets in the post-pandemic era, baby boom retirements, digitalization, and changing social and cultural values around work have amplified pleas for better ways for the U.S. to develop a highly skilled labor force. An education system that normalizes and validates experiential learning can add tremendous value for employers, learners, and society. Simply put, both types of learning—academic and hands-on—are in demand and merit credit and value when they are signaled in the labor market. However, without the active engagement of employers in shaping those hands-on, work-based learning pathways in a transparent and efficient manner, the U.S. will continue to struggle to achieve high-quality hands-on training at the necessary scale. The current system that relies on one dominant path, college for all, simply cannot keep up with the pace of the U.S. economy with classroom education alone, and this system is not set up to have strong collaboration with employers as partners in co-producing a skilled workforce.

Ultimately, focusing on state-level reforms is more likely to have an impact on bridging the chasm between education and employment systems in the near future than an effort primarily targeting federal-level reforms. The federated, decentralized setup of the U.S. education system gives states more authority than the federal government, so states have more leverage to innovate. In addition, the institutional setup of education varies greatly across states, so a one-size-fits-all solution is not likely to work well.

That is not to say that policies and investments at the federal level will be insignificant. Unprecedented federal investments enacted in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act are creating more demand for skilled labor in particular places and industries. States can leverage these opportunities and resources to focus their efforts. In addition, potential federal legislation or policy changes may speed up and/or hinder reforms, such as proposed apprenticeship modernization legislation or the Department of Labor’s January 2024 notice of proposed rulemaking for apprenticeships, both of which may make significant changes to the national apprenticeship system. To the extent that these federal policies help states work from some shared definitions, data definitions, and curricula, they could accelerate state efforts to engage employers more actively as partners in talent development. However, if instead these federal efforts lead to more reporting requirements and more confusion, they could undermine state efforts to get more employers to play an active role in work-based learning pathways.

To examine the question of how key stakeholders can work at the state level to improve the ability of a formal education system to meet employer needs, we considered the deeper, longer-term experience of other advanced economies around the world and shared a few emerging examples in the U.S. Each state will be coming into this work with a different combination of assets, governance structures, and existing policies, so they are not likely to pursue these reforms in the same way. We recommend that advocates for change work at the state level to improve:

- Efficiency: It is important to develop a shared intellectual infrastructure for employers to shape work-based learning skills and occupational pathways to move away from bespoke, one-off programs that are often duplicative and administratively burdensome for employers.

- Transparency: It is crucial to map out how work-based learning programs and pathways fit within an overarching formal education system, which categorizes programs by level and type (academic vs. practical) so that employers can make sense of credentials more easily and individuals can navigate their career and education advancement options.

- Governance: It would be beneficial to establish meaningful authority and a clear role for employers in the professional pathway within that newly integrated system to identify in-demand skills and priority occupations, deliver training, and identify gaps in curricula to keep it up-to-date.

To advance these goals that require working across funding streams and programs, state and local leaders should consider forming a coalition of employers; institutes of higher education; secondary education providers; and other practitioners in workforce development, economic development, and commerce. These cross-sector, cross-agency coalitions are important for building consensus and a shared language for reform. A given state’s coalition can map out a strategy that assesses that state’s assets, challenges, resources, and opportunities. For instance, with support from philanthropists, Indiana has recently formed a coalition to expand youth apprenticeships. A major component of this effort focuses on having employers and CEOs involved, designating priority industry sectors, and working collaboratively with employers in those sectors on a statewide strategy.

In addition to setting up a coalition, leaders among the coalition should consider pursuing regular opportunities for learning and exchanges with leaders in other states, so that individual leaders can build relationships with their peers, collaborate on problem solving, and exchange ideas and lessons learned. Field visits to other states and countries with innovative practices and related professional development activities can help more stakeholders create a shared vision and motivate them to innovate in their own roles. Federal and state policymakers, in partnership with researchers, should also work to establish, gather, and promote the use of shared metrics for success that reflect the goals of employer-education alignment and recognition of work-based learning. For example, having a common approach to measure employer ROI would ultimately support more employer adoption in occupations with positive ROIs.

Reimagining the role of employers in the education and training system will require an all-hands-on deck approach. Below are some recommendations specific to key stakeholders to advance this work.

- U.S. employers can self-organize by industry and/or occupation to play a more active role in talent development. Employers will see more results from their engagement if they can speak as a united voice about the shared talent, skills, credentials, and knowledge needs they have and about related trends over time. The more organized employers are, the easier it is for small- and medium-sized employers to be part of the dialogue, and the easier it is for partners to sync up and respond.

- Employer-serving intermediaries can build on existing sector strategies and infrastructure (and similar promising employer engagement approaches) to streamline employer engagement and to bring more small- and medium-sized businesses to the table. It is important to educate employers about how to set up high-quality work-based learning infrastructure at their workplaces, what their roles and responsibilities are, and how they can assess and improve their ROI on talent investments.

- State agencies and philanthropic funders can consider startup funds for employer-serving intermediaries to convene employers in a given sector, work with employers and educators to design and update curricula, and assess learners’ progress toward achieving key learning milestones.

- Education leaders and training providers can support linkage between the education system and employers by partnering with employer-serving intermediaries to design and update course curricula, through an approach that allows more employers to have input than an advisory committee alone.

- Institutions of higher education and education/workforce agencies can improve access to and awareness of prior learning assessment and/or formally accredit learning in professional and work-based learning pathways, which enables employers to more easily understand and account for the value of work-based learning.

- Funders and state agencies releasing grants can focus on reducing the duplication of outreach to employers by including program incentives that encourage grantees to coordinate outreach to employers and by using performance measures that reward systems- and infrastructure-building rather than pilot programs. Over time, work to streamline and align employer input mechanisms across programs and funding streams, which may also require legislative changes (or at least flexibility for governors or state legislators to have this option).

- Employer-serving intermediaries, funders, and thought leaders can develop branding, outreach, and messaging campaigns for learners, educators, and employers to clarify the roles of each player in new pathways to opportunity; dispel myths about the quality and content of work-based-learning; and make resources and access points more transparent and user-friendly (through tools like online portals, user-centered design, and others). Following the lead of countries with effective professional and technical pathways, employer intermediaries (such as chambers of commerce) should also consider supporting early outreach and career exposure activities (starting in middle school in the U.S.), such as sponsoring career fairs demonstrating a variety of professions and job shadowing to cultivate awareness and better matching with earn-and-learn opportunities later on.

Above all, the U.S. must prioritize employer engagement mechanisms that can resonate beyond just one institution at a time and that champion consistent processes for updating skills frameworks as technologies and work processes evolve over time. These are significant changes in culture, policy, and practice, but if underinvestment in talent continues to be a costly pain point, necessity just may breed invention.