"The man who dies rich dies disgraced."

Andrew Carnegie, The Gospel of Wealth, 1889.

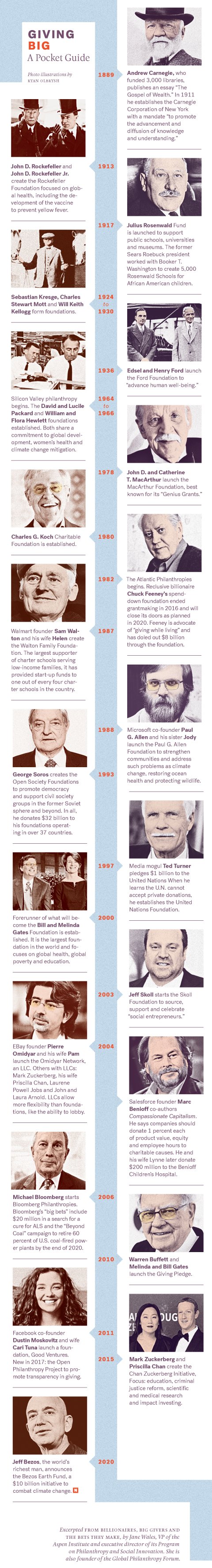

In 2010, Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett started the Giving Pledge, a promise by very rich people to give away a majority of their wealth during their lifetime or in their will. The idea was to change the world of giving by encouraging more people with outrageous amounts of money to give more sooner, and most of all to give differently—to share ideas and best practices and make their giving more effective. Instead of (or perhaps in addition to) spending their money on a new helipad for their yacht in Cap d'Antibes, 209 individuals or couples have publicly promised to give half or more of their money away to those who need it. You'd think that would be cause for celebration, or at least a begrudging "thanks."

Nope.

Why? Maybe it comes back to the fact that we are, in the words of Senator Bernie Sanders, "sick and tired of billionaires," a feeling that has been growing over time—and hasn't seemingly abated even as the rich have stepped up during the COVID-19 pandemic. Maybe it just comes down to envy on our part. Perhaps the idea that a handful of people feel they can save the world feels like hubris. "How dare they?" Maybe the Kochs and Mercers (climate denialism) and the Selzes (antivax) have given philanthropy a bad name.

Whatever the reason, the Pledge has certainly had its critics. On the fifth anniversary, Bloomberg.com analyzed the estates of 10 Pledgers who'd died and found most had not given away half before they died. It concluded that the Pledge was more like joining a "club" than a genuine commitment. In June 2019, in The Chronicle of Philanthropy, journalist Marc Gunther concluded that the Pledge hasn't "turbocharged philanthropy" as intended. He suggested that many Pledgers aren't really living up to their commitment and only joined for the cachet. Kelsey Piper of Vox called the Pledge "disappointing" because more billionaires haven't signed up.

This is the tenth anniversary of the Giving Pledge and the twentieth of what is now the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, or "BMGF," which administers the Pledge. The truth is no one outside Seattle really knows if the Pledge has been a disappointment or a success or something in between. The Gateses and Warren Buffett declined interview requests, but Bill and Melinda did release the following statement to Newsweek. They said:

"When we started the Giving Pledge with Warren Buffett a decade ago, our goal was to encourage more wealthy people to devote that wealth to the benefit of the world. But we weren't sure if the idea would work. How many people would actually choose to give away the bulk of their net worth? The answer, it turns out, is more than we expected."

"In the beginning, Bill, Melinda and Warren did not know how many

people would do it...So against the original expectations,

it's already been a GREAT SUCCESS."

We also spoke with three senior executives at the BMGF and a number of Pledgers. Rob Rosen, director of philanthropic partnerships, oversees the Giving Pledge. He says, "The notion that a hundred people would sign up seemed highly ambitious. Then seven years or so ago, it was 200. Now a stretch goal would be half the billionaires in America [according to Forbes, that would be roughly 300.] So against the original expectations, it's already been a great success."

It's even harder to determine if the Pledge has driven more or faster giving. Rosen says the Pledge has helped some think through "What is the right number?" But the Pledgers we spoke with all said they would have given most of their wealth away anyway. Still, Laura Arnold of Arnold Ventures, the philanthropy she founded with her husband John, believes the Pledge likely has taken the conversation from "abstract to concrete." She adds: "That's very important. From theory to action is critical. Sometimes people want to get involved in philanthropy, but getting started is hard. It really is. The Pledge is a very effective way to do that." The Arnolds, who made their money trading energy futures, were among the first signers and say they were among the most vocal proponents of giving while living.

Nonetheless, BMGF doesn't track how much Pledgers have actually given, because at Warren Buffett's insistence, the Pledge was designed to be a loose moral obligation rather than a tight, legal one. Nor does anyone else track it. Associate Professor Hans Peter Schmitz of the University of San Diego says, "The world of philanthropy doesn't use numbers. It prefers stories." Billionaire giving is particularly hard to track down because much of it is given privately, with little fanfare. The numbers that are out there suggest the rich in general give proportionately less during their lifetimes than average folk, but more when they pass away.

While there's little evidence the Pledge has increased giving, there's also little evidence it hasn't. Gunther found Pledgers who don't appear to have given much at all yet. But it's just as easy to find examples who appear to be living up to the Pledge. There are no official numbers, but various published sources suggest some are on track to meet the Pledge goal. Azim Premji, chairman of Wipro and unofficially the IT czar of India, has given away $21 billion. Hedge fund billionaires Ray and Barbara Dalio: $5 billion. DFS co-founder Chuck Feeney: $9 billion. And of course, Buffett and the Gateses have given more than $90 billion between them, with billions more to come. U.K. couple Jeremy and Hannelore Grantham have given away 98 percent of their wealth to fight climate change. Grantham was a pioneer in index funds.

New England real estate moguls Bill and Joyce Cummings have given away roughly 80 percent of theirs, over $2 billion. Bankers T. Denny Sanford, the late Herb and Marion Sandler, and Bernard and Barbro Osher have given away or are giving away almost all their wealth. As are Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz and his wife, former journalist Cari Tuna. The list of causes supported by Giving Pledgers runs the gamut from reproductive rights (John and Laura Arnold) to education (Premji, the Dalios, the Oshers) to improving the lives of children (Sanford, Chris Hohn) to ProPublica and fighting predatory lending (the Sandlers) to infectious diseases (BMGF, Moskovitz and Tuna) to immigration reform and post-conflict reconciliation (Feeney) to science to animal welfare to educating the next generation of Chinese leaders (Stephen Schwarzman).

As for the Pledge "turbocharging philanthropy" by spurring others to action? Jeff Bezos hasn't signed the Pledge, but it's worth noting that he created the Bezos Earth Fund and promised to give $10 billion for climate change abatement not long after his ex-wife MacKenzie Bezos signed the Pledge.

There is also evidence, again anecdotal, that the Pledge is delivering on the objective of making giving more effective by sharing ideas and best practices. The Gates Foundation organizes an annual retreat for Pledgers. Participants rave about how much they learn and how helpful it is in shaping their philanthropy. Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates and best-selling author says, "It's very difficult to do philanthropy well. There's no framework. There's no philanthropy app. In business, it's easy to tell if something's working. It's harder with philanthropy." Stephen Schwarzman, a hedge fund CEO and, also, a best-selling author, agrees, "It's important to figure out how to intelligently deploy resources. It's not a unique problem, and it helps to get together with other smart people and share ideas."

The Pledge has also inspired other efforts to encourage the rich or soon-to-be rich to give more. That's especially true outside the U.S. where there's less of a tradition of philanthropy. There's the China Global Philanthropy Institute, founded by three Chinese philanthropists, Dalio and Bill Gates to develop philanthropy in China. And something called the Founders Pledge, a London-based effort to get entrepreneurs to commit 2 percent of the proceeds when they sell their companies. So far 1,360 entrepreneurs from 30 countries have signed up. From Brazil there's the Generation Pledge, which asks young heirs to give 10 percent of what they inherit within five years of inheriting, and commit to do good with the 90 percent they keep.

And while he hasn't signed the Pledge, Africa's richest man, industrialist Aliko Dangote of Nigeria, has his own foundation which works closely with the Gates Foundation on issues like polio. Nigeria is expected to be certified polio-free this year. He says he was personally inspired by the Gateses to take on improving the health care system. Now his foundation's work is inspiring others. "More and more people are coming to us asking for advice on how to set up their own philanthropic organizations, and we are always happy to help," Dangote says. "Our belief is that Africa's challenges will have to be solved by Africans ourselves. And we are starting to see more and more people stepping up." His foundation was one of the first in Africa to give money for COVID-19 testing.

Perhaps some of the criticism of the Pledge is fueled by the secrecy surrounding it. According to an article by Carol Loomis in Fortune magazine, the Pledge was created at a private dinner held in 2009, appropriately enough at the very low-key Rockefeller University in New York City. It was hosted by David Rockefeller and led by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. CNN founder Ted Turner, DFS Group co-founder Charles Feeney, fund manager George Soros, KB Home founder Eli Broad, Michael Bloomberg, Oprah Winfrey and another half dozen or so were there. Participants were sworn to secrecy.

They haven't become much more communicative since. Pledgers' names and videos of learning sessions are listed on the website. If they wish they can write a letter explaining their motivations for signing. In addition to being posted online, the letters are displayed at the Smithsonian. But other than that, nada. It's believed that prospects were quietly vetted. Those selected were then invited to join by Melinda and Bill Gates or Buffett. Once they join, they can attend private retreats where the more experienced philanthropists in the group tutor newer ones in the art and science of giving money away, an effective tactic since the rich trust each other more than they do the non-rich. There are also gatherings to share ideas and talk about causes. Pledgers rarely talk about any of it to outsiders.

The Pledge's secrecy, along with suspicion of the uber-rich, make the Pledge an easy target. Still, why dump on people who are trying to help? Pledgers are the good billionaires. Or at least well-intended. As Jason Saul, a Chicago-based expert on philanthropy says, "I'd rather billionaires sign a Giving Pledge than a Taking Pledge." By going public, Pledgers are sticking their necks out. Why not save our self-righteous anger for the 1900 or so billionaires who haven't signed the Pledge? (Forbes says that 1,062 billionaires have seen their wealth drop as a result of COVID-19, and 267 have already fallen off the list.) By criticizing the Pledge, are we non-billionaires discouraging the sort of behavior we should be encouraging? Rather than criticizing Pledgers, should we be encouraging the non-Pledge billionaires to join?

To Sign or Not To Sign

When a multi-millionaire friend asked me what I was working on and I said a story about billionaires who give away half their money, she shrugged and said, "They can afford it." She could also afford it. Giving away half of one's wealth is no small thing, be it 10 billion or 10 bucks. Dangote says: "My wealth will be given away in any case, but there are implications in my religion [Islam] vis-à-vis my heirs. So this is something we are considering, but ultimately it is a family decision." Chuck Feeney's daughter Juliette Timsit says she supports her parents' decision and Dalio says his children do as well. But not every family thinks that way.

Many, though, insist the decision is not really about the money at all, but rather the publicity that comes with it. It's two separate decisions. 1. Give? 2. Sign? Chuck Feeney gave away most of his fortune before the Pledge even existed, but he nonetheless hesitated before signing. According to Jane Wales of the Aspen Institute and founder of the Global Philanthropy Forum, "Chuck is the most reclusive guy ever." His daughter Timsit laughs, "In 1988, I called home from a phone booth in Nevada. I could tell from my mom's tone that something was off. In a hushed and grave voice she told me that my Dad was very upset for having made the Forbes (richest people in the world) list."

Almost-billionaires Craig Silverstein and his wife, Mary Obelnicki, also hesitated before signing. Silverstein is a walking Jeopardy question, like who was the fourth Stooge or the fifth Beatle? In Silverstein's case, he was the third member of the Google start-up with Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Silverstein and Obelnicki have started a foundation called Echidna Giving, which focuses on girls' education. Obelnicki says their decision was made partly to encourage others:

"We could have chosen to be less visible. Craig had already set up an anonymous vehicle for giving, and we had a relatively low public profile. So for us, signing the Giving Pledge and going public was a considered and conscious choice...In Silicon Valley, there is a lot of wealth creation that occurs early in individuals' lives. We wanted to encourage our peers to start early, to find a problem they care about and to work the problem."

For those who don't sign, "privacy" is often cited as the reason why. Dalio says, "The question is always whether the learnings you get from being part of the Pledge are worth the loss of privacy." But it is hard to understand exactly what privacy they're talking about. Those billionaires with huge fortunes, those from multi-generational wealth or those who head eponymous companies already have a public profile. As Schwarzman says, he was already a "quasi-public figure" before signing the Pledge this year. Arnold says, "I do find myself at dinners responding to people's reasons for not signing. Most of the time they say something like 'Oh, we don't want the publicity. We want to stay under the radar.' I tell them that we live in a time where how much wealth you have is already out there."

One non-Pledger declined an interview through an intermediary, citing "privacy." Again, what privacy? He is on the Forbes list, as were his parents. The family name is on dozens of factories and office buildings, including two buildings at a prominent university and their products are in every hospital in America. His family foundation's endowment is on the internet. "Privacy" doesn't make much sense as an excuse not to talk to a reporter, although it does make sense that he might not want to answer questions about his philanthropy. According to an analysis done for Newsweek by DonorSearch, over the last five years the family foundation has only given away $3.6 million. Even when personal gifts are added in, it appears the family has given away less than 1 percent of their wealth. "Privacy" may be his polite way of saying "I have no intention of giving away my money, and don't think I need to explain anything to you."

As with many things, perhaps this is one of those situations where when people say it's not about the money, it really is.

What's Next?

The jury is still out on whether the Giving Pledge is a success. It will be a long wait before the verdict comes in, until at least the first class of Pledgers has died, their estates settled, and an accounting done. That's many years in the future. It may never happen. At present, many fortunes like the Gateses' are growing faster than even the BMGF, the greatest foundation the world has ever known, can give it away—although their fortune did drop by almost seven billion during March according to Forbes.

Nor is it going to be possible to judge whether the Pledge has indeed "turbocharged giving" for a long time. Wales says of the Pledge, "the most important contribution is intangible. It's had a tremendous signaling effect. Now it's become accepted worldwide that any self-respecting billionaire should be involved in philanthropy." Still, so far, only about 10 percent of the world's billionaires and one fourth of those in the U.S. have signed.

It is more likely the Pledge will always be easy to support or easy to criticize. Both Dalio and Rosen worry that negative publicity about the Pledge may have a "chilling effect" not just on Pledging, but on giving. Too bad. The criticism is unlikely to stop. The Atlantic magazine recently resurrected the century-old argument that billionaire philanthropy is a threat to democracy because it gives the privileged few undue influence about who is helped. The magazine argued that instead of philanthropy, billionaires should just pay their damn taxes.

The Urban Institute's Ben Soskis says we are entering a new phase of philanthropy where the public is more critical and less accepting. Una Osili, professor of economics and philanthropic studies at the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, says "After the Epsteins and Sacklers, people are now questioning motives. The challenge is not to let the negative publicity from cases such as Epstein overshadow the role that philanthropy can play in solving problems locally and globally." The late Jeffrey Epstein was a convicted sex offender. The Sacklers own Purdue Pharma, which created and aggressively marketed the opioid OxyContin. Both Epstein and the Sacklers were major philanthropists. But Pledgers aren't Epsteins or Sacklers. Despite the accusation that The Pledge is a vehicle for the unsavory to burnish their reputations, there are only two convicted felons (Michael Milken, Arif Naqvi), a handful of vulture capitalists and one oligarch (Vladimir Potanin) on the list.

In fact, many Pledgers are about as like-able as billionaires can be. Over four fifths are self-made. They form a surprisingly broad cross-section of society—young, old, male, female, old industry, high tech, liberal, conservative, white, Asian, black.

Many Pledger stories are inspiring—like Scotland's Ann Gloag, who got rich from a bus company she started with the money her father got when he was laid off as a bus driver. Or Niu Gensheng, a Mongolian who was sold at birth for seven dollars by his desperate parents. Some are rich because they've come up with things we love—Uber, Netflix, Chobani, Spanx, Kinko's and life-saving bio-med devices. They're billionaires because we made them billionaires. And they are stepping up big time to take on the COVID-19 crisis.

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously said, "Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me." But many aren't really that different. Dalio explains, "Billionaires are mostly middle-class people who accidentally made a lot of money. Most of us come from not much money. We know what it's like." "Accidentally" may be a stretch, but the passion in his voice when he talks about solving inner-city poverty is undeniably genuine.

But there's also a bigger issue at play. On Sunday, February 23, The New York Times ran an editorial criticizing billionaires for making their money by "standing on our backs, pinning us down." It's part of a general trend toward billionaire-bashing. Billionaires aren't a particularly sympathetic segment of the population. They can be tone-deaf. When David Geffen posted a picture of his luxury super-yacht in the Grenadines where he was self-quarantining during the pandemic, the feedback was so nasty that he closed his Instagram account.

Nonetheless, grouping people and picking on that group is dangerous business. It's a cheap trick straight from the demagoguery toolkit. It's OK to criticize immigration policy. It's not OK to paint all immigrants as rapists and murderers. It's OK to criticize a tax system that allows billionaires to avoid paying their fair share—and to call out individual billionaires who do bad things. It's not OK to vilify them as a group, as Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and others have done.

And of all the things billionaires can be criticized for, signing the Pledge shouldn't be one of them. What would critics have billionaires do? Not give? However imperfect, the Pledge is a tool to redistribute enormous amounts of wealth from those who have too much to those who have too little. And to do it now. In an eloquent and thoughtful column at Bolder Giving, a peer-support network for philanthropists, Silverstein and Obelnicki say, "We're still intent on giving our wealth away in our lifetimes. We don't want to leave behind any lasting institutions, just lasting change."

Tell me again why we have a problem with these folks?

Sam Hill is a Newsweek contributor, bestselling author and consultant. He doesn't qualify for The Giving Pledge.

Correction: 4/29; 1:55pm Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, is no longer CEO.