Governments tend to define democracy as narrowly as possible. The story they tell goes as follows: you vote; the majority party takes office; you leave it to govern on your behalf for the next four or five years. If you don’t like one of its policies, your representative will put their own ambitions, party loyalty and pressure from powerful interests aside to ensure your voice is heard.

We can trust the government to spend our money wisely; to defend minorities against more powerful or larger groups; to resist undemocratic forces such as oligarchs, the media they control and corporate lobby groups. We can trust it to ensure everyone’s needs are met; workers are not exploited; our neighbourhoods and quality of life are not sacrificed to corporate profits. We can trust it not to abuse the political process; not to wage wars of aggression against other nations; not to break the law. There cannot be many people who have lived in the UK – or many other nations – for the past few years and still believe this fairytale.

We have seen what happens if we leave politics to governments. Fairly elected or not, they will, without effective public pressure, abuse their power. They will change political rules to favour their party, subordinate public interest to that of corporations and billionaires, beat up vulnerable groups, sacrifice our common future to expediency and impose ever more oppressive laws to bind us.

Trust in governments destroys democracy, which survives only through constant challenge. It requires endless disruption of the cosy relationship between our representatives and powerful forces: the billionaire press, plutocrats, political donors, friends in high places. What challenge and disruption mean, above all, is protest.

Protest is not, as governments like ours seek to portray it, a political luxury. It is the bedrock of democracy. Without it, few of the democratic rights we enjoy would exist: the universal franchise; civil rights; equality before the law; legal same-sex relationships; progressive taxation; fair conditions of employment; public services and a social safety net. Even the weekend is the result of protest action: strikes by garment workers in the US. A government that cannot tolerate protest is a government that cannot tolerate democracy.

Such governments are becoming a global norm. In the UK, two policing bills in quick succession seek to shut down all effective forms of protest. They enable the police to stop almost any demonstration on the grounds that it is causing “serious disruption”, a concept so loose, it could include any kind of noise. They would ban chaining yourself to railings or other fixtures, and “interfering” with “key national infrastructure”, which could mean almost anything. They expand police stop and search powers, an effective deterrent to civic action by black and brown people, who are disproportionately targeted by them. They can even ban named people from engaging in any protest, on grounds that appear entirely arbitrary. These are dictators’ powers.

In the US, state legislatures have been undermining the federal right to protest, empowering the police to use catch-all offences such as “trespass” or “disrupting the peace” to break up demonstrations and make arrests. Proposed laws in states such as Oklahoma and New Hampshire have sought to grant immunity to drivers who run over protesters, or vigilantes who shoot them. In Russia, a new law against “discrediting the armed forces” has been used to prosecute dissenters engaging in actions as mild as writing “no to war” in the snow. Similar draconian laws are being imposed by governments in many other nations.

Why do governments want to ban protest? Because it’s effective. Why do they want us to accept their narrow vision of democracy? Because it makes our power ineffective.

The protests governments seek to ban broaden the scope of democracy. They permit us to challenge malfeasance and resist oppressive policy. They are the motor of political change, and the early warning system that draws attention to the crucial issues governments tend to neglect. The extraordinary people in these images understand this – from suffragettes picketing the White House in 1917 to Patsy Stevenson being manhandled by police at last year’s Sarah Everard vigil; from relatives of those killed at Amritsar in India in 1919 to those taking to the streets after George Floyd’s murder in the US.

Almost everything of importance is disintegrating fast: ecosystems, the health system, standards in public life, equality, human rights, terms of employment. It’s happening while elections come and go, representatives speak solemnly in parliament or Congress, earnest letters are written and polite petitions presented. None of this is enough to save us from planetary and democratic collapse. Business as usual is a threat to life on Earth. Disrupting it is the greatest civic duty of all.

They will continue to demonise us as a threat to the democracy we seek to protect. They will continue to arrest us and raise the penalties for being a good citizen. And we will continue to come out in defiance, as people have done for centuries, even when facing state violence and repression. Everything we value depends on it.

Pussy Riot play Red Square, 2012

“Pussy Riot was formed in October 2011, because we didn’t want Putin to stay in power for ever, and we felt that if we didn’t get rid of him, he would bring a great deal of pain to our country,” says Nadya Tolokonnikova, a founding member of the Russian protest group-cum-punk band.

On 20 January 2012, eight members of Pussy Riot climbed on to the platform in front of St Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow’s Red Square and staged a guerrilla performance of their song Putin Zassal (Putin Has Pissed Himself). Operating anonymously at the time, the women wore brightly coloured ski masks as they sang and set off smoke bombs.

“We had religiously rehearsed the whole of January,” Tolokonnikova recalls. “Coming to the square many times in advance; trying to calculate when there would be fewer police cars; getting climbing equipment for our shoes because the podium was covered in ice; discussing in detail what to do if we were detained.”

Immediately after the performance, the women were detained. “We spent eight hours at the police station and were let go. Exhausted. But happy.”

That day is remembered as Pussy Riot’s big breakthrough. After their next performance – held inside Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour – three members, including Tolokonnikova, were prosecuted for hooliganism, and the veil of anonymity was lifted. Yet through multiple arrests and jail terms – and as Putin has tightened his grip on power – the group remains determined to give voice to the resistance. In the wake of the invasion of Ukraine, the stakes have only grown. “Protest activity is becoming increasingly dangerous in Russia,” Tolokonnikova says. “You face 15 years in jail for calling a war a war, not a ‘special military operation’. And still, people protest every day. Not because they want to be heroes: because they can’t lie to themselves.” GS

Police dogs attack civil rights demonstrators in Birmingham, Alabama, 1963

In early 1963, Martin Luther King Jr described Birmingham as “probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States”. He and other civil rights leaders organised a campaign of nonviolent protests, placing students at the centre of the movement. Eugene “Bull” Connor, the city’s commissioner of public safety and a staunch segregationist, directed the use of fire hoses and police dogs to quell the demonstrations. Charles Moore’s images of a dog attacking a young man on 3 May 1963 drew national attention to the Birmingham movement – and led to Connor’s ousting from office. GS

The lady in red at Gezi Park, 2013

Around three million people took part in the wave of protests against the government that swept Turkey in the summer of 2013. It began with a small, peaceful protest on 28 May against the planned demolition and redevelopment of Taksim Gezi Park in Istanbul; police then attempted to disperse protesters using teargas and water cannon. This image of activist and academic Ceyda Sungur being teargassed quickly became an emblem for the movement. Images of the “lady in red”, as she was dubbed, appeared on posters and online graphics, galvanising protests across the country. GS

Barbara Kruger’s vision goes global, 2020

The artwork Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) was originally produced by Barbara Kruger as a poster urging people to attend the March for Women’s Lives in Washington DC in April 1989. The demonstration was organised in protest against the Republican administration’s attempts to overturn Roe v Wade that year. Formerly an editorial designer at Condé Nast, Kruger knew how to create a memorable image: “I was able to use the fluencies I developed with pictures and words and transform them into my own engagements as an artist.”

Today, Kruger’s rallying cry for bodily autonomy continues to appear around the world. In this photograph, a Polish version of the poster, first produced in 1991, is shown plastered on a street in Szczecin in 2020. Abortion laws in Poland are among the most restrictive in Europe. “Language has power. And the velocity and accessibility of that power is dependent on its readability,” Kruger says of her decision to translate the text on the poster in Poland.

How does it feel to see her artwork still circulating so widely – especially in the wake of the renewed assault on reproductive freedoms around the world? “It is tragic that the war against women’s bodies, against their power and agency, and against the notion of a multiplicity of genders, is continuing in the most brutal of ways,” Kruger says. GS

Rosa Parks takes her seat on the bus, 1956

This was taken on 21 December 1956, the day of the desegregation of the public transportation system in Montgomery, Alabama. More than 12 months earlier, Rosa Parks had been arrested for refusing to give up her seat for a white man, sparking the 382-day Montgomery bus boycott – the first large-scale demonstration against segregation in the US. The white man in this photo was not a random passenger but veteran UPI reporter Nicholas Chriss: the shot was staged by an uncredited photographer to illustrate this important victory. GS

Tiananmen Square, 1989: a young boy …

“This was the only moment in my career when I instinctively knew it was going to be just fine – that I had a great shot,” Dario Mitidieri says. It was the Italian-born photojournalist’s final evening in Beijing, where he had flown to document the protests in the square. He had a return ticket to the UK the following morning.

When he first arrived in the Chinese capital, Mitidieri recalls that the atmosphere had been “quite joyful”. “It was like a massive student party, they were dancing in the streets at night, singing Chinese opera. We knew there were secret police filming everywhere but there was no sense of danger,” he says. But then soldiers began assembling around the square. Mitidieri’s photo of a young boy sitting on the shoulders of a relative, above a sea of helmets, was shot at around 6pm on 3 June 1989, only a couple of hours before the massacre began. In order to get the best angle, he climbed on to the seat of a nearby bicycle, held upright by two student protesters.

The image would become a potent symbol of the innocence of the protesters who were violently oppressed when the troops were sent in that night. Mitidieri, who never learned the name of the boy in the photo, thinks of his record of the events at Tiananmen Square as “a true example of the value of the work photojournalists do”. He compares it to the current situation in Ukraine: “We have this propaganda coming from the Russian government, but the rest of the world is very well aware of what’s going on because of the presence of photographers and journalists documenting it all, risking their lives.” GS

… and Tank Man

This photograph was taken by Stuart Franklin, a British photographer, on 5 June 1989, the day after the Tiananmen Square massacre, in which it’s believed as many as 10,000 pro-democracy protesters in Beijing were killed by troops sent in to quash the demonstrations. A lone protester, dubbed “Tank Man”, stood blocking the path of a column of tanks leaving the square. Footage of the incident was smuggled out of China, with the still-unidentified man instantly becoming an icon in the western world. As Franklin put it: “Here was a modern-day version of David and Goliath.” GS

The self-immolation of Thich Quang Duc, 1963

“No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one,” John F Kennedy said about this image of an elderly Buddhist monk taking his own life, on 11 June 1963, in protest against the persecution of Buddhists by South Vietnam’s largely Catholic government. American photojournalist Malcolm Browne won a Pulitzer prize for his documentation of the shocking event. GS

Resistance at the Gaza border, 2018

A’ed Abu Amro was among tens of thousands of Palestinians taking part in weekly protests at the Gaza border from 2018-19. Among their demands were an end to the blockade and right of return for Palestinian refugees. This image – by Gazan photographer Mustafa Hassona – of the young man with the flag of Palestine and a slingshot was seen around the world, drawing comparisons to Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 painting Liberty Leading the People. Abu Amro was later shot and injured by Israeli troops at another protest. GS

Emma Sulkowicz carries a mattress, 2014

There aren’t many student art projects that receive as much attention as Emma Sulkowicz’s final-year thesis at Columbia University in New York. For Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight), Sulkowicz vowed to carry a mattress wherever they went on campus until the school agreed to expel a fellow student whom they had accused of rape. The performance continued until their graduation – and became a potent symbol of protest against rape culture in universities. “That image,” Hillary Clinton said in 2015, “should haunt all of us.” GS

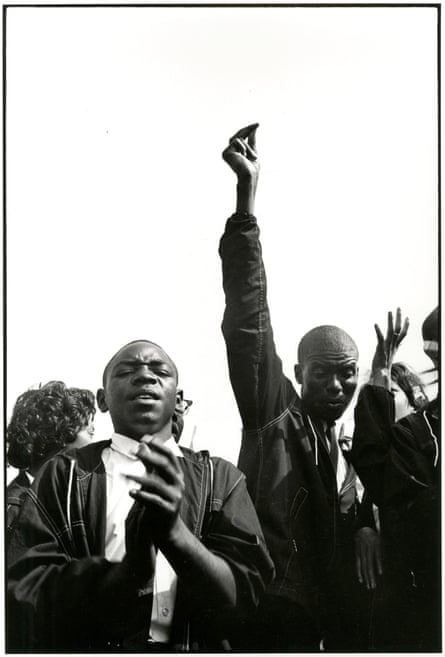

The March on Washington, 1963

On 28 August 1963, a quarter of a million people marched on the US capital to protest for civil rights in America; this was the day that Martin Luther King Jr made his famous “I have a dream” speech. Danny Lyon was a staff photographer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and close friends with the activist and later congressman John Lewis, who helped organise the march. “I spent the night prior to the march sleeping on the floor of John Lewis’s small hotel room,” he remembers. “It was very hot, and very sunny, just the worst light to make photographs.”

This image, of a group of high-school students singing at the march, later became a symbol of the civil rights struggle, and was used as a poster by the SNCC throughout the 60s. The unusual angle was a result of Lyon trying to get other nearby photographers out of the frame: “I fell to my knees to shoot, and shot up to the sky.”

The picture has had a powerful afterlife. In 2020, as the city of Louisville banned street protests in the wake of the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, Black Lives Matter artist-activists led by Darius Dennis painted a vast, 45ft-high mural of the photograph on the wall of a government building in downtown Louisville. For Dennis, the image represented “the spirit of protest history”; by displaying it publicly at a moment when protest was banned, his team wanted to make “these moments of black and brown and Indigenous people more accessible than they are in our schools”. FB

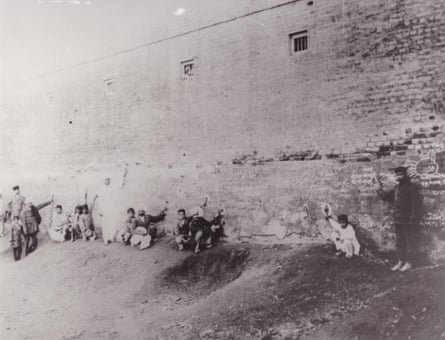

Aftermath of the Amritsar massacre, 1919

In 1919 a peaceful crowd gathered in an open area called Jallianwala Bagh, in the Indian city of Amritsar, to protest against the British authorities’ arrest of pro-independence leaders Saifuddin Kitchlew and Satyapal. The crowd was surrounded by troops from the British Indian army who, under orders from the acting brigadier general, Reginald Dyer, began to fire on the protesters, killing many hundreds of people – estimates suggest 370 to 1,000.

A young photographer called Narayan Vinayak Virkar arrived to document the aftermath. These images are very different from the rest of his work, which largely consists of sumptuous portraits of nationalist leaders such as Gandhi and Subhas Chandra Bose; instead Virkar took a series of sparse crime scene pictures, with the bullet holes from the shooting circled in white chalk. Relatives of those killed point to the holes.

For art historian Christopher Pinney, Virkar’s work “is a very significant moment” in the history of photography. In the 19th century it had been used as a tool of scientific or political authority, but in the 20th century, photographers such as Virkar began to use it to challenge the power structures around them. “Virkar undoubtedly saw his images as involved in a fightback against colonial oppression,” Pinney says. He sees a link between Virkar and the citizen journalists of today who document wrongdoing by the powerful. FB

The Friday of Victory on Tahrir Square, 2011

“This was taken from my friend’s balcony,” recalls Egyptian-Lebanese photographer Lara Baladi. During the initial 18-day uprising in Egypt in 2011, when thousands gathered to protest against President Hosni Mubarak’s authoritarian rule, the flat overlooking Tahrir Square became a meeting place for journalists and activists, “always filled with people working, texting, tweeting”.

Previously Baladi had been documenting the movement down below, but on 18 February, she wanted to see the view from above. It was the week after Mubarak had been toppled, “so that day was named the Friday of Victory. It was a beautiful sunny day,” she remembers. As she watched people in the square celebrate, two young men emerged next to her; they had just bought a massive bale of fabric at the textile market, “basically 100 metres of the Egyptian flag”. Taking hold of either side of the fabric, they threw it down. “In no time it unrolled all the way into the crowd. As soon as it reached the square, people caught it.” Minutes later it was stretched out and knotted to other pieces of fabric, and Baladi took the picture: “It all happened very fast.”

Looking back, for her, this photograph marks “a turning point in the uprising … the victory, the height of the revolution, before reality kicked in and the social divisions and nuances began to surface.”

The events of the last 10 years have confirmed for her that “change does not begin with the uprising. What happens before and after it is just as important, if not more. Revolution is a continuous process.” FB

Irish women walk for abortion rights, 2016

In May 2018, two-thirds of Irish voters opted to legalise abortion in a referendum pro-choice activists had long called for. A defining image of the campaign was of a march two years earlier outside the Irish embassy in London. “We wanted to make a visual statement that might reach decision-makers at home,” says Hannah Little (front). “We decided 77 women should walk silently with suitcases towards the embassy, the number of women then travelling from Ireland to Britain every week to access terminations.

“People who question if a protest accomplishes anything don’t see the butterfly effect: strangers meet, swap details, start a campaign. That’s exactly what happened here.” The London-Irish Abortion Rights Campaign met with MPs, launched legal cases, raised money for pro-choice causes, held protests and mobilised Irish voters abroad. “I don’t see myself in this photo at all. Oddly, I never have,” Little says. “I see young women who are angry and ready to take power back. It resonates with people because we look unstoppable. And we were!” GS

May Day in Mexico, 1926

Italian photographer Tina Modotti became famous for the images she produced in Mexico in the 1920s of working-class life and political organising. This image of a workers’ May Day parade in 1926 was reprinted multiple times within her lifetime and reflects her stylistic mixture of art photography and reportage. In 1930 she was arrested and given an ultimatum: she could either cease her communist activities or leave Mexico. She chose to leave. FB

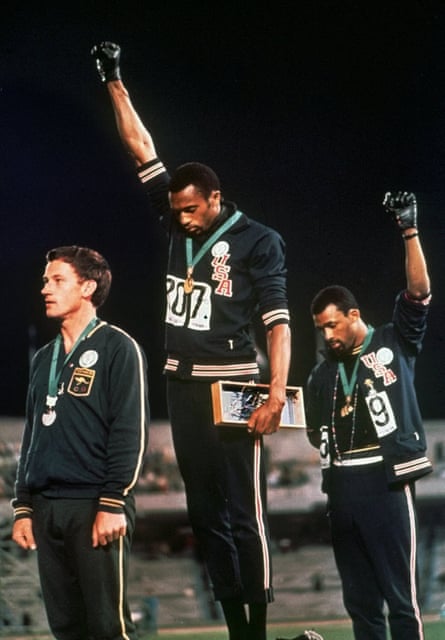

Black power on the Olympic podium, 1968

“You could have heard a frog piss on cotton,” John Carlos (right) said in an interview with Gary Younge in 2012 of the moment he and Tommie Smith raised their fists in a black power salute at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, during the medal ceremony for the 200m race. “There’s something awful about hearing 50,000 people go silent.” The silence was followed by a torrent of racial abuse and though their protest made them famous around the world, it had grave repercussions for both men, whose careers suffered. Carlos had no regrets, however: “I had a moral obligation to step up. Morality was a far greater force than the rules and regulations they had.” FB

MLK and the March on Montgomery, 1965

On 25 March 1965, Martin Luther King Jr led thousands of civil rights protesters to the capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, after a five-day march that started in Selma; 25,000 people joined in across the 80km march, demanding the right to vote. Moneta Sleet Jr covered the landmark event as a photojournalist for Ebony magazine. FB

The Handmaids go to Washington, 2017

Is the dystopian future envisioned in The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood’s novel turned TV show about a theocratic regime that strips women of their basic freedoms, already here? In recent years, the red cloaks and white bonnets worn by the handmaids of Gilead have become a familiar feature at protests on women’s issues around the world. The group of women standing outside the US Capitol in this image from 2017 were demonstrating against a bill that sought to defund the sexual healthcare provider Planned Parenthood. GS

Blessing the protesters at Euromaidan, 2014

“Maidan was the first act in a great historical movement,” wrote Jérôme Sessini prophetically in 2019. “It was just the beginning of a coming confrontation on a much larger scale.” The Magnum photographer covered the protests in central Kyiv that led to the ousting of the pro-Russia president Viktor Yanukovych in 2014. Sessini was present during a period of extreme violence, when snipers killed at least 70 people; he captured the events with a series of extraordinarily dramatic and disturbing images. In this photograph, an Orthodox priest blesses the protesters on a barricade on 20 February 2014. FB

The aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, 2020

Associated Press photographer Julio Cortez captured this image just before midnight on 28 May 2020, the third day of protests after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. With its charged symbolism – the United States Flag Code says a flag should never be flown upside-down, “except as a signal of dire distress in instances of extreme danger to life or property” – the photograph conveys the deep sense of anger and injustice that would go on to fuel a mass movement of anti-racism protests across the globe. GS

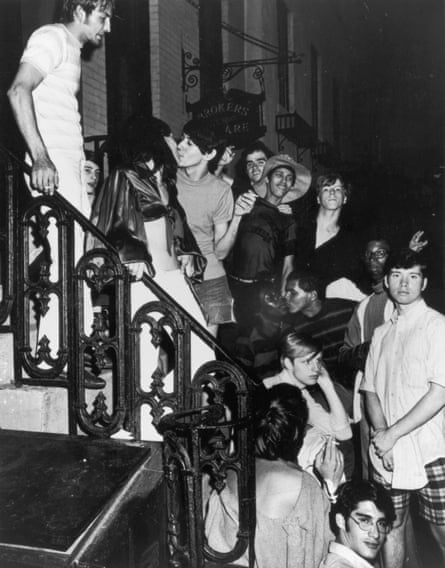

After the raid on Stonewall, 1969

In the early hours of 28 June 1969, a police raid on the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York, prompted a spontaneous outburst of resistance that lasted for six days and was a watershed moment for LGBTQ+ rights. This photograph of young rioters gathered outside the boarded-up inn after the raid, shot by Fred W McDarrah for the Village Voice newspaper, captures the celebratory atmosphere that prevailed as gay and trans people refused to submit to state-sponsored oppression. The first gay pride march was held a year later to commemorate the event. GS

Standing Rock v the Dakota Access Pipeline, 2016

From April 2016, members of the Standing Rock and other Native American communities began to protest against construction of a pipeline in North Dakota, on the basis that it would affect local water supplies and cross sacred native lands. Barack Obama’s administration halted construction, but Donald Trump would later reverse this decision. The pipeline remains in operation today. FB

Thai rubber duck protests, 2020

In November 2020, images of Thai pro-democracy protesters using inflatable rubber ducks to shield themselves from police water cannon went viral. They had originally been bought for protesters to float down the Chao Phraya River near Bangkok’s parliament, but after the images were publicised, they became an unlikely symbol of the protest. FB

Protest, Tokyo, 1969

This enigmatic image by the Japanese photographer Shomei Tomatsu presents a blurry figure caught in the act of throwing a stone in a protest against the Vietnam war. Tomatsu, whose subjects had included the vast changes taking place in postwar Japan, as well as the lingering traumas of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, was known for formal experimentation and unusual compositions, which inspired a whole generation of photographers in Japan. FB

The Soweto Young Lions student uprising, 1976

On 16 June 1976, thousands of black schoolchildren from the township of Soweto in Johannesburg, South Africa, took to the streets, protesting against a decree that all black schools must teach in Afrikaans – what Desmond Tutu called “the language of the oppressor”. The children were initially hesitant to be photographed – the Johannesburg-born photographer Peter Magubane convinced them, he later recalled, by telling them “struggle without documentation is not struggle”. The images would prove vital when coverage of the brutal police response – at least 176 people were killed – began to spread around the world, triggering mass outrage and firing up the anti- apartheid movement. GS

Japan’s students and farmers v a new airport, 1971

In 1960s Japan, a coalition of thousands of leftwing student activists and farmers came together to wage a years-long campaign against the construction of a new international airport in a rural area 40 miles east of Tokyo. The biggest clash at the Narita international airport construction site erupted in September 1971, when 5,000 police were sent in to expropriate the land. The airport finally opened in 1978, after many delays. GS

The first Earth Day, 1970

On the first Earth Day, held in cities across the US on 22 April 1970 to support environmental protection, an estimated 20 million people took to the streets for clean-ups, marches and performances. This photo, of student Peter Hallerman, became an emblem of the modern green movement that was born that day. GS

Soviet tanks roll into Prague, 1968

The Prague spring began on 5 January 1968, when Alexander Dubček took over the Czechoslovakian Communist party from his Stalinist predecessor; he introduced reforms that distanced his party from Moscow and promised “socialism with a human face”. Seven months later, Soviet tanks invaded and Dubček was eventually deposed. Josef Koudelka took about 5,000 photographs that week documenting acts of resistance by civilians but his identity was kept anonymous to prevent reprisals. After smuggling his film abroad, Koudelka fled the country, revealing himself to be the “Prague Photographer” only following the death of his father in 1984. GS

#Notabugsplat, 2014

A group of artist-activists laid out a vast image of a child in a Pakistani field to pique the conscience of US drone operators who watched the border with Afghanistan from above. The portrait is by Noor Behram, who worked in North Waziristan, an area targeted by drone strikes. The girl pictured lost both her parents to one in 2010. FB

The woman with the handbag, 1985

A small neo-Nazi rally in the Swedish city of Växjö made worldwide news when this image of a woman striking a skinhead with her handbag began to circulate. Danuta Danielsson, a 38-year-old Jewish woman whose mother had survived the Holocaust, hijacked the demonstration by the Nordic Realm party on 13 April 1985, in an impulsive counterprotest that has since been memorialised in multiple statues. GS

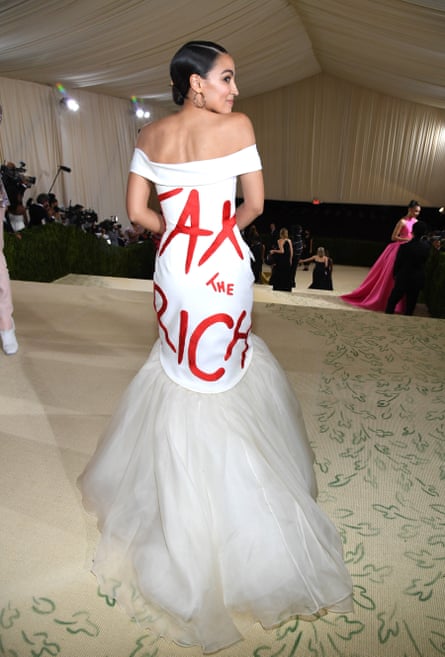

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s dress, 2021

The Met Gala in New York is known for attracting outlandish outfits and wealthy guests, with tickets reportedly costing around $35,000. In 2021, the Democratic congresswoman caused controversy with her gown bearing the message “Tax the Rich” emblazoned across the back, created by the designer and activist Aurora James. Critics charged her with hypocrisy; she maintained it was worthwhile because it created “a conversation about taxing the rich in front of the very people who lobby against it”. FB

Colombians vogue for change, 2021

Mass protests broke out in Colombia on 28 April last year in response to proposed government reforms, including increased taxes and an overhaul of the healthcare system. Lasting six weeks, the protests were met with violent crackdowns resulting in dozens of deaths and hundreds of injuries. But amid the repression, one image of joyful resilience stood out: the moment when three activists ascended the steps of the National Capitol in Bogotá and starting vogueing.

“We decided to protest because, as LGBTQI+ people, all the government reforms affect us much more,” says Piisciis (pictured centre), a non-binary activist who created the music for the performance and invited fellow voguers Axid Ebony and Nova Ebony to collaborate on the steps. “There is very little representation at these marches, so I wanted to open this dialogue.”

The trio found themselves dancing metres away from the Esmad, Colombia’s notorious riot police. “At that moment, I saw a lot of fear in Nova and Axid’s eyes; I also felt it,” Piisciis says. “Everything went well, but it could have been catastrophic.” The dancers continued for a few minutes, cheered on by fellow protesters. Initially, the police seemed unsure what to do, but then, “It turned into chaos: there were explosives, stones, weapons, and we had to run.” The impact of the protest for the queer community in Colombia was, Piisciis says, epic. “It was a moment of empowerment, strength and representation. If in the future there are history books, surely we’ll be in them.” GS

Resistance at the Woolworth lunch counter, 1963

In the spring of 1963, a sit-in was organised by students and staff of Tougaloo College, at a Woolworth lunch counter in Jackson, Mississippi, which had a “whites-only” policy. Anne Moody, who went on to become a famous author, is seated to the right, with student Joan Trumpauer and professor John Hunter Gray. Over the course of a few hours, an increasingly rowdy white mob pulled the hair of the women, dumping mustard and condiments over them, and attacked Gray, cutting his face and neck with brass knuckles and broken glass. Gray later recalled the atmosphere as “a lavish display of unbridled hatred”. FB

A defiant menorah, 1931

Rachel and Rabbi Dr Akiva Posner were a Jewish couple with three children, living in Kiel, Germany, in the early 1930s. As part of Hanukkah celebrations, the menorah must be prominently displayed; but it can be hidden during a time of persecution. Rachel documented the moment – just over a year before Hitler took power – when the rabbi defiantly lit their menorah in the window, facing a building decked with Nazi flags. The Posners fled Germany two years later. FB

Prams in Lviv, 2022

On 18 March 2022, 23 days into Russia’s war on Ukraine, 109 empty buggies were laid out in a square in Lviv, each representing a child who had been killed. Today the official estimate stands at more than 300. FB

Jan Rose Kasmir plants a flower in a bayonet to protest against the Vietnam war, 1967

Jan Rose Kasmir, 17, holds a chrysanthemum before a row of bayonet-wielding soldiers. This shot was taken by the Magnum photographer Marc Riboud on 21 October 1967 at the March on the Pentagon, a rally in Washington DC attended by 100,000 anti-war protesters. It would become the defining image of that movement. The soldiers, Kasmir later said, “were just as much a victim of the war machine as anyone else”. GS

A woman slows down Seoul’s riot police, 2015

Getty photographer Chung caught the moment a brave woman sat in front of riot police to protect a larger group of protesters, during anti-government protests in Seoul on 24 April 2015. FB

Hong Kong umbrella movement, 2019

During the pro-democracy protests that took place in Hong Kong in 2014, many protesters used umbrellas to defend themselves from pepper spray. After journalists referred to the demonstrators as the “umbrella movement”, umbrellas quickly became a powerful symbol of the independence movement, carried by protesters to signal their allegiance and also used in art installations and countless memes. FB

Alaa Salah becomes a symbol of a new Sudan, 2019

“We were seeking freedom, and we were seeking our dreams, and we were seeking a new Sudan,” recalls artist and musician Lana H Haroun of the 2019 revolution. Initially, forces loyal to president Omar al-Bashir had cracked down violently on protesters. But then some members of the army began to defend them, creating a safe space outside the presidential palace. People travelled from all over Sudan to be there.

“Every day I was there, capturing photos,” Haroun recalls. “It felt like history itself.” One day, she noticed people rushing towards a figure addressing the crowd, a 22-year-old called Alaa Salah. Haroun took four photos, and shared the best one online. It went viral, first on social media, then in newspapers around the world. “A lot of things happened after that.” Previously it had felt as if there was very little global coverage of what was going on in Sudan, but after Haroun’s picture it suddenly felt as if “everybody in the world was focusing on what is going on in Sudan”.

Women played a powerful and visible role in the protests; for Haroun, the picture was a strong message that women can lead. Salah went on to speak at the UN and was a Nobel peace prize contender. FB

Words of protest across the world

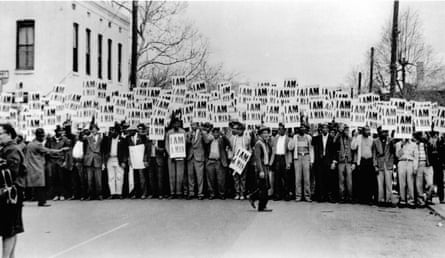

Sanitation workers strike in Memphis, 1968

This famous chapter of the civil rights movement was captured by African American photojournalist (later revealed to be an FBI informant) Ernest C Withers. On 28 March – just days before his assassination – Martin Luther King Jr arrived in Memphis to lead a march in support of the city’s 1,300 striking sanitation workers. Spurred by the deaths of two garbage collectors due to malfunctioning equipment, the strikers were calling for higher pay and safer working conditions for the city’s Black employees. Their slogan was a simple but effective assertion of dignity: “I am a man.” GS

The royals in Jamaica, 2022

Prince William and Kate Middleton made an ill-fated visit to the Caribbean earlier this year, where they were met by protesters calling for reparations, an official apology and the cutting of ties with the British monarchy. Around the time of the visit, Jamaica confirmed its plan to begin removing the Queen as sovereign. FB

Greta Thunberg goes on strike, 2018

Today, Greta Thunberg is one of the most famous living activists on the planet. But nobody knew who she was when, on 20 August 2018, the 15-year-old set up camp outside the Swedish parliament and declared that she would not attend school until after the general elections the following month. Her goal was simple: to force action on the climate crisis. “The situation we are in is very dire and it seemed like no one was doing anything and someone needs to do something,’” she recalls. “I thought, if this doesn’t work, then I’m going to try something else until I find something that works. I had no idea it was going to take off like it did.”

The School Strike for Climate quickly became a global movement, with children around the world organising walk-outs. The following year, at the UN climate action summit in New York, Thunberg condemned world leaders for their failure to effect any meaningful change. “It was like a very weird movie that was way too unrealistic and cliched to be any good,” Thunberg says of the seismic public response. “But it’s also quite hopeful, because it shows that the most unexpected things can happen in a very short amount of time.”

On why young people have played such a significant role in climate protests, Thunberg says: “It feels like our natural state of mind is to rebel. We don’t use the excuse that it’s always been this way.” But also “it’s children who will live in this world, experience the consequences much more. It’s closer to home.”

After taking a year-long break from education to focus on climate activism, Thunberg is about to enter her final year of school and continues her protest by skipping classes every Friday. Looking at the photo from her original demonstration, she says she still has the banner, but now keeps it at home to avoid rain damage. The bright yellow raincoat, which she borrowed from her dad, is also “still around … It’s still his, but I still steal it,” she jokes. And if she could say anything to the girl in that image, what would it be? “I would probably say: start crocheting and knitting earlier, because it’s really fun and it keeps you focused,” she says with a laugh. “But that’s probably not the answer you want!” GS

A Russian woman stands up for Ukraine, 2022

In a country where protest is brutally oppressed, the bravery of Russians who publicly oppose the war in Ukraine has not gone unnoticed. The 76-year-old artist and activist Yelena Osipova became the face of the anti-war movement after footage of her arrest by police in St Petersburg on 2 March was seen around the world. In this image, the woman dubbed the “grandmother for peace” is holding her handmade protest banners while a crowd of supporters can be glimpsed in the background. GS

Suffragettes at the White House, 1917

On 10 January 1917, a dozen suffragists gathered silently at the gates of the White House, becoming the first group to picket the presidential residence. Dubbed the Silent Sentinels, they held up banners calling on President Woodrow Wilson to support a constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote. Two thousand protesters joined the picket, which continued until 4 June 1919, when the 19th amendment was eventually passed. Many were arrested and jailed for their involvement – reports of the prisoners’ mistreatment played a key role in garnering wider public support for women’s suffrage. GS

Arlen Siu and a Sandinista funeral in Nicaragua, 1978

When Susan Meiselas arrived in Nicaragua in June 1978, she had no idea that a popular insurrection was about to erupt. The American photographer stayed in the country for 13 months, documenting the uprising of the FSLN, popularly known as the Sandinistas, against the US-backed Somoza dictatorship. “The world didn’t know much about what was happening in Nicaragua,” Meiselas says. “It was a time when we were not seeing images – which is unimaginable now.”

Meiselas felt compelled to witness the events as they unfolded. This image depicts a funeral procession in Jinotepe for recently assassinated student leaders. The protesters are holding up a large photograph of Arlen Siu, a singer and Sandinista who had been killed by the National Guard three years earlier. Siu went on to become a revolutionary icon.

Meiselas attributes the impact of her photograph in part to the contrast between the monochromatic portrait of Siu and the vivid colour of the surrounding scene. “There was a lot of criticism at that time of working in colour – very few newspapers published colour,” she recalls.

Today, of course, almost everything is shot in colour and Meiselas, who is president of the Magnum Foundation, is widely recognised for her work. But she doesn’t see the plaudits as solely for her. Of the long afterlife of the image of protesters in Jinotepe, she says: “Now Arlen Siu has more of a profile. I think of it as her getting her honour.” GS

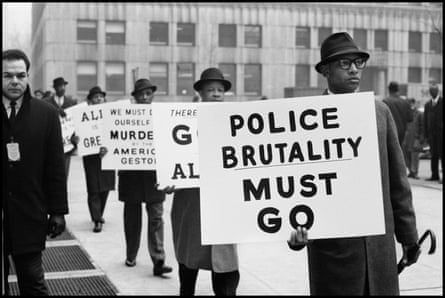

Black Muslims stand up to police violence, 1963

Gordon Parks was the first African American staff photographer employed by Life magazine. This image from a protest in Harlem in 1963 – spurred by the police shooting of seven unarmed black men outside a Nation of Islam mosque in Los Angeles the previous year – is part of his series documenting the black Muslim movement. Parks was assigned the story after several white journalists failed to gain access to the group’s leaders. GS