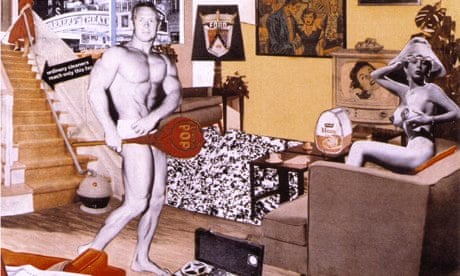

Richard Hamilton was an artist whose considerable ambition was to "get all of living" into his work. In his epoch-making collage of 1956, Just What Is It That Makes Today's Homes So Different, So Appealing?, the living space is crowded with up-to‑the-minute objects of desire: the TV set, the vacuum cleaner, the tinned ham, the tape recorder, the body builder's muscles, the cone-shape coolie hat perched on the sexy naked housewife on the sofa. Hamilton's consumer's catalogue is well observed and playful. But at a more profound level it is horribly disquieting. No other work of art of its period expresses so precisely the jarringly ambivalent spirit of the age.

In Britain in that early postwar era there was a sudden thrilling influx of sophisticated, streamlined consumer goods from the US. It was bonanza time for British housewares, too, as the government-supported Council of Industrial Design (now the Design Council) campaigned to improve standards in British manufacturing and a new breed of industrial designers emerged from British art schools. In 1956, exactly coinciding with Hamilton's collage, the Design Centre opened in the Haymarket, a heaven for aspirational homemakers. There was even a royal seal of approval when Prince Philip's inaugural prize for elegant design was awarded to the Prestcold Packaway refrigerator.

But, as Hamilton was well aware, a backlash was beginning. Richard Hoggart, in The Uses of Literacy (1957), voiced the misgivings of many in lamenting the pervasive influence of American mass culture, "full of corrupt brightness, of improper appeals and moral evasions". There was a dawning consciousness that have-it-all housewives could be less than happy. The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan's bestselling analysis of female domestic frustration, would be published in America in 1963. Labour-saving appliances were certainly seductive, but there was now a movement of suspicion and distrust that one might define as Tupperware resistance. As an artist, Hamilton thrived on this ambivalence.

That Hamilton was anti-capitalist is an understatement. But he still adored the uninhibited plenty of American culture. Like other contemporary artists, Allen Jones being an obvious example, he devoured and then recycled the imagery of popular American magazines. He spoke of this as "plundering the popular arts". By popular arts, Hamilton emphatically did not mean the folk arts, which turned him very squeamish. The neo‑romantics, the Kitchen Sink School and the St Ives artists were similar betes noires.

For Hamilton, popular art meant the unselfconscious and the vulgar as epitomised by the "POP" on the phallic lollipop in the Just What Is It collage. Pop art, as he defined it in a now famous letter to the architects Alison and Peter Smithson, was: "Popular (designed for a mass audience), Transient (short‑term solution), Expendable (easily forgotten), Low cost, Mass produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous and Big business." His own work is far from easily forgotten. Hamilton's rare meditative intelligence caused him to arrive at a form of pop art that lingers in the mind.

In the 1950s, he was a leading member of the Independent Group, an offshoot of the by then more elderly and settled Institute of Contemporary Arts. John Osborne's Look Back in Anger opened at the Royal Court in 1956. Young Independent Group members were the angries of the art world, the gang was described by one member as "small, cohesive, quarrelsome, abusive". Hamilton's wife Terri developed a technique at meetings of responding to ideas she disapproved of by standing up and miming the pulling of a lavatory chain.

Besides the Hamiltons and Smithsons, the Independent Group included the artist Eduardo Paolozzi, the photographer Nigel Henderson, the critic Reyner Banham, the architect Jim Stirling and the architecture student Cedric Price. On the fringes was the then young radical furniture and textiles designer Terence Conran. What a wonderful subject for a group biography the defiantly multidisciplinary Independent Group would make. According to Lawrence Alloway, another key figure of the movement, they began "to see the work of art in a changed context, freed from the iron curtain of traditional aesthetics". Note the iron curtain image. These were the eerie years of the cold war.

They worked in the expectation of change. What other response was possible for a young artist? It was that or obliteration. Hamilton was crucially involved in the Independent Group's collaborative exhibition This Is Tomorrow held at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, in London, in August 1956. It marked the first appearance of Just What Is It, which was used both as an illustration for the catalogue and a poster for the exhibition. Hamilton was also largely responsible for the Fun House installation that veterans of This is Tomorrow remember as the sensation of the show.

Fun House was an immersive experience affecting all the senses. Within the architect John Voelcker's outer structure Hamilton assembled a visually provocative assemblage of images from advertising, movies and comics as well as more conventional fine art. Pop music blared out from the jukebox. The exhibit included a monumental bottle of Guinness, a 16ft model of Robbie the Robot, borrowed from MGM's Forbidden Planet film set, and a surreal voice from within the robot opened the exhibition.

In retrospect, it may seem absolutely obvious that Hamilton's Fun House had a serious purpose in exploring the complexities of visual perception and in extending the boundaries of art. It is clear that it had considerable influence not just on Cedric Price's architectural "fun palace" concepts of the early 60s but also on the coming riot of psychedelic "happenings". But, in its day, the exhibit was distinctly controversial, and it will be fascinating to see the recreation of Fun House in the Hamilton retrospective at Tate Modern.

Hamilton's art contained the shock of the eclectic. His all-embracing attitudes caused widespread puzzlement. He challenged the traditional hierarchy of values, the purist view held by the British art establishment of what was proper subject matter for a work of art. Hamilton was a knowledgable, deeply serious artist who loved and respected the great artists of the past. But he was also determinedly responsive to the modern. The critic David Sylvester, a friend of Hamilton's, described this as verging on madness, a consuming obsession with "modern living, modern technology, modern equipment, modern communications, modern materials, modern processes, modern attitudes".

Why, when cars had so greatly transformed the world we live in, were they virtually absent from the world of art? This question, posed by Hamilton in 1957, was definitively answered by two of his Pop paintings of the period, Hommage à Chrysler Corp and Hers Is a Lush Situation. It is not irrelevant that Hamilton's father worked for a time as a demonstration driver for a car showroom in London's West End. Hamilton himself grew accustomed to the gently purring engines of the luxury Jaguars and Bentleys. His complex and beautiful works align the contours of the car with the welcoming eroticism of the female body, ideas that were (and still are) such a feature of product-promotion techniques.

Like the car, the pop-up toaster had not been a favoured subject for those who considered themselves bona fide artists. In the early postwar decades there had been a definite if unspoken division, based on snobbery, between fine artists and industrial designers. Hamilton rather heroically resisted such divisions. His own early experiences had been varied. He had worked at EMI in wartime as a jig and tool draughtsman. He had been part of the design team for the first British transistor radios, involved in breaking the boundaries of new technologies. The Braun electric toaster, which he made the subject of the haunting image Toaster of 1967, was part of a lifelong fascination with industrial design.

The catalogue for the Tate Modern retrospective includes a touching photograph of Hamilton in Germany, standing outside the Hochschule für Gestaltung at Ulm. It is 1958. He is in the pose of pilgrim, the visitor from Britain at the gates of the school of design founded on Bauhaus principles, which, beyond all others, was setting new standards of European consumer goods design. The photograph reminds us of how Hamilton loved quality. There was a close connection in personnel and ethos between the high‑end Braun electronics company and the school at Ulm.

Among the design cognoscenti of the period, Braun products were the creme de la creme, the must-have objects. I remember a time when no trendy living room would seem complete without its Braun stereo player. All image-conscious offices had Braun electric desk fans. In a perceptive essay in the exhibition catalogue, Alice Rawsthorn views Braun as having played a similar role in 1960s and 1970s consumer culture as the role Apple played for later generations. The elegance and rigour of Braun products were drawn on by Hamilton in several of his most peculiarly disconcerting works. The Braun catalogues were plundered not only for the pop-up toaster but also the portable combination grill and even the immaculate typography.

His own admiration for Dieter Rams, Braun's chief designer, verged on the ecstatic. Hamilton said: "I have for many years been uniquely attracted towards his design sensibility; so much so that his consumer products have come to occupy a place in my heart and consciousness that Mont Sainte-Victoire did in Cézanne's." All the same – and typically – this attitude of reverence did not prevent him from affixing to the top of his own Braun electric toothbrush the giant set of sugar-pink confectionery teeth his young son had bought him as a present from Brighton. The assemblage was later made into a multiple, The Critic Laughs (1968), complete with its own Braun-style packaging.

He translated so explicitly the language of things. One might see in Hamilton's candy-topped Braun toothbrush a parallel to Marcel Duchamp's urinal. Both artists pursued investigations of the ready-made found object, the quest described by Hamilton as "a search for what is epic in everyday objects and attitudes". He became a friend of Duchamp's and was closely involved with the revival of Duchamp's reputation in the years before his death in 1968. Hamilton was the organiser of the first major Duchamp retrospective in Europe, held at the Tate, for which he made the Duchamp-approved facsimile of The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass). The reconstruction is now in Tate Modern's own collection and will feature in the current exhibition.

Hamilton's long connection to James Joyce is perhaps less obvious but equally profound. He first started reading Ulysses in the two-volume Odyssey edition as a much-needed diversion during military service with the Royal Engineers. In 1947, he began to make studies for illustrations to the text. In 1981, with Joyce's centenary celebrations looming, he resumed work on the illustration series. The full collection of more than a hundred drawings, etchings and prints made to illustrate Ulysses was finally exhibited at the British Museum in 2001 in an unforgettable convergence between literature and art.

What Hamilton loved so much about Joyce was the mastery of language, the fluency of movement, the "polyphony of tongues, codes, ideolects" that released and inspired Hamilton himself to try out "some implausible associations in paint". It was Joyce, as Hamilton would tell you, who made him the artist that he was. He responded to the Joycean ebb and flow of narrative, the lack of resolution, the endless possibility of taking the narrative anywhere.

There are overtones of Joyce, as well as Jean-Paul Sartre's Huis Clos and even Dante, in Hamilton's painting Lobby, derived from a postcard of a Berlin hotel foyer with its disconcerting stairway and its endlessly reflecting mirrors. Hotel of dreams indeed. Or hotel of one's worst nightmares? Like all Hamilton's interiors it is a space of strange allusiveness and ambiguities. As with Fun House, Hamilton's weirdly underpopulated Lobby will be recreated in three dimensions in the exhibition at Tate Modern.

They called him "Daddy Pop" but Hamilton was so much more. As Norbert Lynton wrote in his Guardian obituary in 2011, this was an artist who was "passionately responsive to his own time". He gave current events an almost epic quality. See what he does with Swingeing London 67, a series of paintings and a screenprint based on a press photograph of Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser handcuffed together in a police van arriving at court to be charged with illegal possession of drugs. The handcuffs are prominent. How Hamilton loved hardware. By 1967, swinging London had lost its early innocence. The establishment was panicking. "There are times when a swingeing sentence can act as a deterrent", as the judge at the trial was grimly to pronounce.

There is a growing tendency to denigrate the 60s as an overblown period when nothing of significance actually happened. Hamilton, of all people, knows this is not so. He made wonderful work through the whole of his long lifetime. But it is his art of those early postwar decades, when the look and feel of Britain was changing fundamentally, that makes this retrospective an unmissable event.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion