Robert Ford (outlaw)

Robert Ford | |

|---|---|

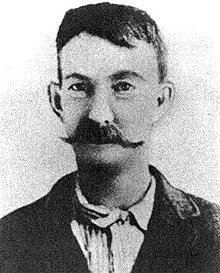

Robert Ford, c. 1883 | |

| Born | Robert Newton Ford January 31, 1862 Ray County, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | June 8, 1892 (aged 30) Creede, Colorado, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Resting place | Richmond Cemetery in Richmond, Missouri |

| Occupation(s) | Gangster; Saloon owner |

| Known for | Assassination of Jesse James |

| Parent(s) | James Thomas and Mary Bruin Ford |

Robert Newton Ford (January 31, 1862 – June 8, 1892)[1] was an American outlaw who killed fellow outlaw Jesse James on April 3, 1882. He and his brother Charley, both members of the James–Younger Gang under James's leadership, went on to perform paid re-enactments of the killing at publicity events. Ford would spend his later years operating multiple saloons and dance halls in the West.

Ten years after James's death, Ford was himself the victim of a fatal shot to the neck by Edward Capehart O'Kelley in Creede, Colorado, dying at only 30 years old. While initially buried in Creede, his remains were later exhumed and reinterred in his hometown of Richmond, Missouri.

Early years[edit]

Robert Ford was born in 1862 in Ray County, Missouri, to James Thomas and Mary Bruin Ford as the youngest of seven siblings. As a young man, Ford came to admire Jesse James for his Civil War record and criminal exploits, eventually getting to meet him in 1880 at the age of 18.

Ford's brother Charley is believed to have taken part in the James–Younger Gang's Blue Cut train robbery[2] in Jackson County, west of Glendale, Missouri (renamed Selsa and now part of Independence), on September 7, 1881.[3][4]

Joining the gang[edit]

In November 1881, after the train robbery, James moved his family to St. Joseph, Missouri, and intended to give up crime. The James gang had been greatly reduced in numbers by that time; some had fled the gang in fear of prosecution, and many of the original members were either dead or in prison after a botched bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota.

After the train robbery, James' brother Frank James had also decided to retire from crime and moved East, settling in Lynchburg, Virginia.[5]

By the spring of 1882, with his gang depleted by arrests, deaths and defections, James thought that he could trust only the Ford brothers.[6] Charles had been out on raids with James before, but Robert was an eager new recruit. The Fords resided in St. Joseph with the James family, where Jesse went by the alias Thomas Howard.

Hoping to keep the gang alive, James invited the Fords to take part in the robbery of the Platte City Bank in Missouri, but the brothers had already decided not to participate; rather, they intended to collect the $10,000 bounty placed on James by Governor Thomas T. Crittenden. In January 1882, Robert Ford and gang member Dick Liddil had surrendered to Sheriff James Timberlake at their sister Martha Bolton's residence in Ray County. They were brought into a meeting with Crittenden, as they had been around James' cousin Wood Hite the day Hite was murdered. Crittenden promised Ford a full pardon if he would kill James, who was by then the most wanted criminal in the US.[7][page needed] Crittenden had made capturing the James brothers his top priority; in his inaugural address he declared that no political motives could be allowed to keep them from justice. Barred by law from offering a sufficiently large reward, he had turned to the railroad and express corporations to put up a $5,000 bounty for the delivery of each of them and an additional $5,000 for the conviction of either of them.[8]

Living with the James family, the Fords became part of the daily routine, and James's wife cooked for them. They were nervous and bored, looking for opportunity, and feeling restless. The confession of Liddil to participating in Hite's murder made the news, and pressure began to build around James.[citation needed]

Killing Jesse James[edit]

On April 3, 1882, after eating breakfast, the Fords and James went into the living room before travelling to Platte City. By reading the daily newspaper, James had just learned of gang member Liddil's confession for participating in Hite's murder and grew increasingly suspicious of the Fords for never reporting this matter to him. According to Robert Ford, it became clear to him that James had realized they were there to betray him. However, instead of scolding the Fords, James walked across the living room to lay his revolvers on a sofa. He turned around and noticed a dusty picture above the mantel, and stood on a chair to clean it. Robert Ford drew his weapon and shot James in the back of the head.[10][11]

After the killing, the Fords wired Crittenden to claim their reward. They surrendered themselves to legal authorities but were dismayed to be charged with first degree murder. In one day, the Ford brothers were indicted, pleaded guilty, and sentenced to death by hanging, but two hours later Crittenden granted them a full pardon.[12]

Later years[edit]

Public opinion turned against the Fords for betraying their gang leader, and Robert was seen as a coward and traitor for killing James. This sentiment clashed with the general public opinion at the time of James's death that it had been time for James to be stopped by any means. For a period, Robert earned money by posing for photographs as "the man who killed Jesse James" in dime museums.[13] He also appeared on stage with his brother Charles, reenacting the murder in a touring stage show.

Charles, terminally ill with tuberculosis and addicted to morphine, died by suicide on May 4, 1884.[14] Soon afterward, Robert Ford and Dick Liddil relocated to Las Vegas, New Mexico, where they opened a saloon.[15] According to legend, Ford had a shooting contest with Jose Chavez y Chavez, a comrade-in-arms of Billy the Kid's during the Lincoln County War. Ford lost the contest and left town.[16]

On December 26, 1889, Ford survived an attempt on his life in Kansas City, Kansas when an assailant tried to slit his throat.[17] Within a few years, Ford settled in Colorado, where he opened a saloon and gambling house in Walsenburg. When silver was found in Creede, Ford closed his saloon and opened one there.[18] Ford purchased a lot and on May 29, 1892, opened Ford's Exchange, said to have been a dance hall.[19] Six days later, the entire business district, including Ford's Exchange, burned to the ground in a major fire. Ford erected a tent saloon to operate from temporarily until his former establishment could be rebuilt.[citation needed]

Death[edit]

Three days after the fire, on June 8, 1892, Edward O'Kelley entered Ford's tent saloon with a shotgun. According to witnesses, Ford's back was turned. O'Kelley said, "Hello, Bob." As Ford turned to see who it was, O'Kelley fired both barrels, killing Ford instantly. He became "the man who killed the man who killed Jesse James". He never explained his motive for the murder.

O'Kelley's sentence was commuted because of a medical condition and a 7,000-signature petition in favor of his release, and he was released on October 3, 1902.[19][20][21] O'Kelley was subsequently killed on January 13, 1904, while trying to shoot a policeman.

Ford was buried in Creede. His remains were later moved and reinterred at Richmond Cemetery in his native Richmond in Ray County, Missouri; "The man who shot Jesse James" was inscribed on his grave marker.[22]

Cultural depictions[edit]

Films[edit]

The James and Ford brothers were popular subjects of Western films in the 1940s and 1950s:

- In Jesse James (1939), Ford is played by John Carradine.[23]

- In The Return of Frank James (1940), a highly fictionalized film about Frank James hunting down Bob and Charley Ford, John Carradine reprised his role. The film, directed by Fritz Lang, is a sequel to Jesse James, which also features the Fords.

- In I Shot Jesse James (1949), directed by Samuel Fuller, Ford is portrayed by John Ireland.[24]

- In The Great Missouri Raid (1951), directed by Gordon Douglas, Ford is portrayed by Whit Bissell.[25][self-published source?][26]

- In The True Story of Jesse James (1957), Ford is portrayed by Carl Thayler.[27][self-published source?]

- In Hell's Crossroads (1957), Robert Vaughn plays Bob Ford.[28]

- In The Long Riders (1980), Nicholas and Christopher Guest play Bob and Charley Ford.[29][30]

- In the made-for-TV movie The Last Days of Frank and Jesse James (1986), Bob Ford was played by Darrell Wilks. The role of Jesse is played by Kris Kristofferson, Frank James is played by Johnny Cash. Willie Nelson and David Allen Coe also have roles in this film.

- In Frank & Jesse (1995), Jim Flowers plays Bob Ford.[31]

- In The Plot to Kill: Jesse James (2006), and Jesse James: American Outlaw (2007) (both TV movies produced by The History Channel), Ford is portrayed by James Horton.

- In The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007), based on the historical novel by Ron Hansen, Ford is played by Casey Affleck, with Brad Pitt as Jesse James.[32][33] Affleck was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

Literature[edit]

- Ron Hansen's historical novel, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (1983), is based on deep research of the figures and their times.

- In Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle's novel Inferno (1976), Ford is depicted as being in Hell as a traitor.

Music[edit]

- The lyrics of the folk song "Jesse James" (first recorded in 1924 and later recorded by others, such as The Kingston Trio, Bruce Springsteen and The Pogues) refer to Ford as "Well it was Robert Ford/that dirty little coward/I wonder now how he feels/for he ate of Jesse's bread/and he slept in Jesse's bed/and he laid poor Jesse in his grave."

- In the Bob Dylan song "Outlaw Blues", Dylan alludes to Ford with the lines, "I ain't gonna hang no picture/Ain't gonna hang no picture frame/Well I might look like a Robert Ford/But I feel just like a Jesse James".

- Elton John's song "I Feel Like a Bullet (In the Gun of Robert Ford)", from the Rock of the Westies (1975) album, refers to a betrayal in a romantic relationship that is metaphorically likened to Jesse James' assassin.

- In Warren Zevon's song "Frank and Jesse James", Ford is noted in the lyrics, "Robert Ford, a gunman/In exchange for his parole/Took the life of James the outlaw/Which he snuck up on and stole".

- In The Sugarhill Gang's song "Apache", Ford is referenced in the lyrics, "My tribe went down in the Hall of Fame/'Cause I'm the one who shot Jesse James".

- In a song by Australian singer-songwriter Dave Graney, ‘Robert Ford on the Stage’, from Graney's 1989 Album, ‘My Life on the Plains’ (Dave Graney with the White Buffaloes). Graney's song is a potent evocation of Ford's tortured psychological state after he killed the notorious Jesse James.

Radio[edit]

- Sam Edwards portrayed Bob Ford in the CBS radio show Crime Classics episode, The Death of a Picture Hanger (July 20, 1953).[34][self-published source?]

Television series[edit]

- Tyler MacDuff played Bob Ford in the episode "Jesse and Frank James" of Jim Davis's syndicated Stories of the Century.

- Bobby Jordan played Ford in an episode of Dale Robertson's NBC series Tales of Wells Fargo.[35]

- Martin Landau portrayed Robert Ford in the ABC/Warner Brothers western series, Lawman in the episode "The Outcast".[36]

- Charles Aidman guest starred in the episode "Bob Ford" in the first season of Shotgun Slade, starring Scott Brady.

- Roy Jenson played Bob Ford in the Hondo episode "Hondo and the Judas".

- In the NCIS episode "Parental Guidance Suggested", Ducky states that "Robert Ford comes to mind" as he opines to DiNozzo in his autopsy findings on an open murder case that "shooting someone unarmed in the back is such a cowardly act".

- The Little House on the Prairie 4th season (1977) episode "The Aftermath" depicted Ford, played by Tony Markes, as a student at Walnut Grove School.

- Timeless featured an alternate timeline where Garcia Flynn shoots and kills Robert and Charley Ford moments before they shoot Jesse James, played by Daniel Lissing. James then helps Flynn locate another member of the future lost in time, pursued by the real-life versions of the Lone Ranger and Tonto.

References[edit]

- ^ Weiser-Alexander, Kathy. "Robert Ford". Legends of America. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Yeatman, Ted P. (2000). Frank and Jesse James. Cumberland House Publishing. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-5818-2325-7.

- ^ Settle, William A. (1977). Jesse James was His Name. Bison Books. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-8262-0052-5.

- ^ "New Facts on the 'Blue Cut' and Glendale". Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Yeatman, Ted P. (2000). Frank and Jesse James. Cumberland House Publishing. pp. 263–264. ISBN 978-1-5818-2325-7.

- ^ King, Susan (September 17, 2007). "One more shot at the legend of Jesse James". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

By 1882, the James gang was a shadow of its former self on account of arrests, death and defections. The only people James felt he could trust were Charley Ford, who had been a veteran of James' raids, and his brother Robert Ford, who was eager to prove himself.

- ^ Stiles, T.J. (2003). Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-3757-0558-8.

- ^ Nix, Elizabeth (May 31, 2023). "7 Things You May Not Know About Jesse James". History. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Williams, Michael D. (29 November 2017). "Death of the man who killed, the man who killed Jesse James". Medium.com. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Stiles, T.J. (2002). Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. Knopf Publishing. pp. 363–375. ISBN 978-0-3754-0583-9.

- ^ Yeatman, Ted P. (2000). Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend. Cumberland House Publishing. pp. 264–269. ISBN 978-1-5818-2325-7.

- ^ "Jesse James's Murderers. The Ford Brothers Indicted, Plead Guilty, Sentenced To Be Hanged, And Pardoned All In One Day". The New York Times. April 18, 1882. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ^ Yeatman, Ted P. (March 8, 2007). "Jesse James's Assassination and the Ford Boys". Wild West. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ "Ford Family archival data". Ancestry.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012.

- ^ William Preston Mangum II (April 2007). "Liddil Rode Beside The James Brothers; But later turned against them". Vol. 19, no. 6. Wild West. p. 20.

- ^ Hurst, James W. (January 10, 2003). "Jose Chavey y Chavez Hombre Muy Malo". Southern New Mexico.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011.

- ^ "Bob Ford's Narrow Escape. An Admirer Of Jesse James Tries To Cut His Throat" (PDF). The New York Times. December 27, 1889. Retrieved December 9, 2008.

- ^ Rocky Mountain News. March 7, 1892. p. 2.

- ^ a b Ries, Judith (1994). Ed O'Kelley: The Man Who Murdered Jesse James' Murderer. St. Louis, Mo.: Patches Publication. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-9344-2661-9.

- ^ Warman, Cy (1898). Frontier Stories, 'A Quiet Day In Creed'. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 93–101. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ The Wild Bandits of the Border. Chicago: Laird & Lee. 1893. pp. 355–363. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ Brookshier, Linda (October 2, 2009). "The man who killed Jesse James, Descendant of Robert Ford visits the area bringing answers about the past". Richmond Daily News. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ Smith, Ronald L. (2009). "The Horror Hams: Laird Cregar, John Carradine and Basil Rathbone". Horror Stars on Radio: The Broadcast Histories of 29 Chilling Hollywood Voices. McFarland & Company. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-7864-5729-8.

- ^ Meuel, David (2015). "Introduction: The Dark Cowboy Rides into Town". The Noir Western: Darkness on the Range, 1943–1962. McFarland & Company. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7864-9452-1.

- ^ Rowan, Terry (2016). "Herbie the Lowie Bug". Character-Based Film Series. Vol. Part 1. Lulu.com. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-3650-2128-2.[self-published source]

- ^ Nash, Jay Robert; Ross, Stanley Ralph (1986). The Motion Picture Guide. Vol. 3. Cinebooks. p. 1100. ISBN 978-0-9339-9703-5.

- ^ Reid, John (2005). Cinemascope Two: 20th Century-fox. Lulu.com. p. 181. ISBN 978-1-4116-2248-7.[self-published source]

- ^ Vaughn, Robert (2008). A Fortunate Life: Behind-the-Scenes Stories from a Hollywood Legend. Macmillan Publishers. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4299-6150-9.

- ^ Cole, Jake (October 3, 2017). Gonzalez, Ed; Cinquemani, Sal (eds.). "The Long Riders". Slant Magazine. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Johns, Paul (October 27, 2015). "The Missouri outlaws of the late 1800s who terrorized the nation". Buffalo Reflex. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ Boggs, Johnny D. (2011). Jesse James and the Movies. McFarland & Company. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-7864-8496-6.

- ^ Bauer, Alex (January 7, 2017). "Casey Affleck's First Run-In With 'Oscar'". Medium. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Honeycutt, Kirk (August 30, 2017). "The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford". The Hollywood Reporter. ISSN 0018-3660. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Walker, J.P. (2015). The American Old West: Gangs, Outlaws & Gunfights: Gangs, Outlaws & Gunfights. Lulu.com. p. 311. ISBN 978-1-3129-4896-9.[self-published source]

- ^ Chance, Norman (2011). Who was Who on TV. Xlibris Corporation. p. 293. ISBN 978-1-4568-2456-3.

- ^ "Lawman 5 the Outcast". Archived from the original on September 2, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

Further reading[edit]

- Ries, Judith. Ed O'Kelley: The Man Who Murdered Jesse James' Murderer. St. Louis, Mo.: Patches Publication. 1994

- Yeatman, Ted. Frank and Jesse James Nashville: Cumberland House, 2001.

External links[edit]

- Ford on Legends of America

- http://www.ericjames.org official website for the family of Jesse James: Stray Leaves, A James Family in America Since 1650 Archived 2019-02-28 at the Wayback Machine

- "Robert Ford and his Colorado saloon", photos from the U.S. National Archives and Library of Congress, Awesome Stories website

- "Stories of the Century: "Jesse and Frank James"". IMDb.

- ""Jesse James" on Tales of Wells, Fargo". IMDb. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- Robert Ford at Find A Grave

- 1862 births

- 1892 deaths

- People from Ray County, Missouri

- People from Walsenburg, Colorado

- 1882 murders in the United States

- 1892 murders in the United States

- Outlaws of the American Old West

- American murder victims

- American people convicted of murder

- Murdered criminals

- James–Younger Gang

- People murdered in Colorado

- Deaths by firearm in Colorado

- American prisoners sentenced to death

- Saloonkeepers

- Prisoners sentenced to death by Missouri

- Recipients of American gubernatorial pardons

- People convicted of murder by Missouri

- Gunslingers of the American Old West

- 19th-century American criminals

- People from Mineral County, Colorado