A Timeline of United States Currency

Have you ever reached into your wallet for one of those crinkled green bills and thought, ‘How does this little piece of paper control my entire freaking life? How did I get here?”

Or maybe you’ve wondered why you’ve seen about five different versions of a $20 bill over the course of your lifetime.

What’s up with that?

The history of American currency not only spans centuries, but also boasts quite the fascinating and, shall we say, colorful past.

Not only is this pretty interesting stuff, but it will help you make sense of how we arrived at our current situation of fiat currency, a central bank, and a dollar that is rapidly losing value. And what’s that old saying about history repeating itself? Knowing where we’ve been and how we got there always gives you an edge as an investor, as you may be able to predict trends that are giving you deja vu.

Plus you’ll learn more about how the dreaded Federal Reserve came to be and the history from which their behaviour stems. While you may be sick of hearing about the fed, what they say and do moves markets, and as an investor, you have to be aware of what they’re saying, thinking, and planning.

United States currency has been an evolutionary process that walks hand-in hand with the growth of our nation, often changing in times of crisis -like the Great Depression or September 11th- or as a response to a frustrated society struggling to create a monetary system that would actually function correctly and restore confidence in the American dollar.

From purchasing power, to the size, shape and color of bills, to the creation of the independent central bank, read on for a run-down on the United States history of what makes the world go round; money.

1690: Colonial Cash

In 1690, early Americans in the Massachusetts Bay Colony were the first to issue paper money to meet high demands for trade and as a response to the shortage of coins, which were the primary form of money at the time.

The first paper money was issued to pay for military expeditions, but other colonies followed suit and, although this early money was supposed to be backed by gold or silver, some colonists found that they could not redeem the paper currency as promised, and it quickly lost its worth.

1739: Franklin and Counterfeiting

But where were these colonial bills being created? Benjamin Franklin had a printing firm in Philadelphia that printed paper currency with nature prints. These were completely unique, raised impressions of patterns cast from actual leaves, which added a counterfeit to the money. Benji’s innovative method was not completely understood until centuries later.

1764: British Ban

For years Britain had been placing restrictions on colonial paper money, and in 1764 they finally ordered a complete ban on the issuance of paper money by the Colonies.

1775-1791: The Dawn of U.S. Currency As We Know It

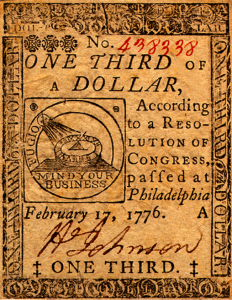

The Continental Congress had to do something to finance the American Revolution, so they printed our brand spankin’ new country’s first ever paper money, known as “continentals.” This was the dawn of fiat currency as we know it today.

Continental One-Third Dollar Bill

Source: Wikipedia.org

These paper money notes didn’t have solid backing, were counterfeited easily, and were issued in such large quantities to so many people that, what do you think happened? You guessed it – inflation.

It started off pretty mild, but as the war trudged on there was massive acceleration in inflation. The phrase “not worth a continental” became part of the common lexicon, meaning something was entirely worthless.

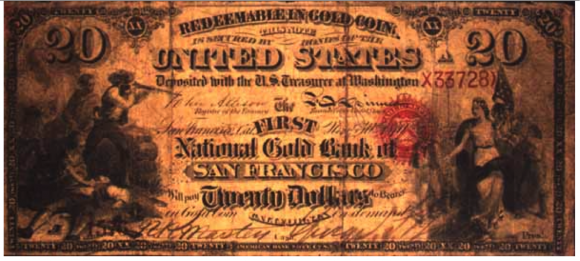

First Charter Original Series note with Allison-Spinner signatures and a small red seal with rays. This was one of the most popular Gold Bank notes issued in California in the 1870s.

Source: MindSerpent.com

1791-1811: Central Banking – Let’s Give This a Shot

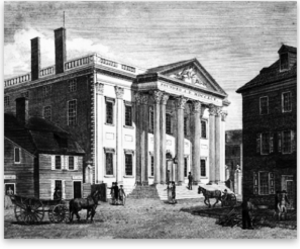

At the time, Alexander Hamilton was the Treasury Secretary. He’s the guy who urged Congress to establish the First Bank of the United States in 1791 to help the government handle war debt. Hamilton was also the architect of the bank, headquartered in Philadelphia. It was the largest corporation in the entire country, and was dominated by money interests and big banking.

It started out with a capital of $10 million, but most Americans were strongly against the idea of a large and powerful bank. And, the government’s war debt was largely paid off, so when the bank’s 20-year charter finally expired in 1811, Congress refused to renew it by one vote.

Alexander Hamilton

Source: Buzzle.com

First National Bank, Philadelphia

Source: SeekingAlpha.com

1816-1836: Let’s Try That Again…

Federal debt started stacking up again with the War of 1812, and the political climate once again found itself entertaining the concept of a central bank. By only a small margin, Congress agreed to charter the Second Bank of the U.S.

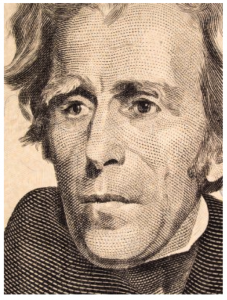

In 1828 Andrew Jackson was elected president. Jackson was a notorious foe of the central bank and vowed to destroy it. His point of view struck a chord with most Americans, and when the Second Bank’s charter expired in 1836, it was, to the shock of no one, not renewed.

Andrew Jackson

Source: WiseGeek.org

1836-1865: The Free Banking Era

During what is known as the Free Banking Era, state-chartered banks and unchartered “free banks” took hold. Banks began issuing their own money notes that could be redeemed in gold or coins, and offered demand deposits to enhance commerce.

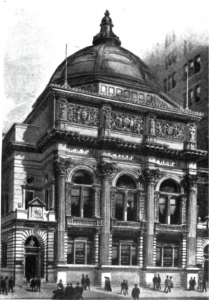

This caused a big jump in the volume of check transactions. In response, the New York Clearing House Association was established in 1853, which provided a way for the city’s banks to formally exchange checks and settle accounts.

The New York Clearing House depicted in the 19th century

Source: Wikipedia.org

1863: Passing of the National Banking Act

During the Civil War, the National Banking Act of 1863 was passed. Abraham Lincoln signed what was originally known as the National Currency Act, which for the first time in American history established the federal dollar as the sole currency of the United States. Having everyone on the same currency provided for nationally chartered banks, whose circulating notes had to be backed by U.S. government securities.

There was an amendment to the act, which required taxation on state bank notes but not national bank notes, which effectively created a uniform currency for the nation. Even though they were being taxed on their notes, state banks continued to flourish in light of the increasing popularity of demand deposits, which, as we told you, took hold during the Free Banking Era.

1873-1907: Financial Freak Outs

While there was a little bit of currency stability for our rapidly growing country, thanks to the National Banking Act of 1863, bank runs and financial panics were far from a thing of the past, and perpetually plagued the economy.

These bank panics were so universal that they made their way into mainstream popular culture. You might remember this clip from the old classic It’s a Wonderful Life:

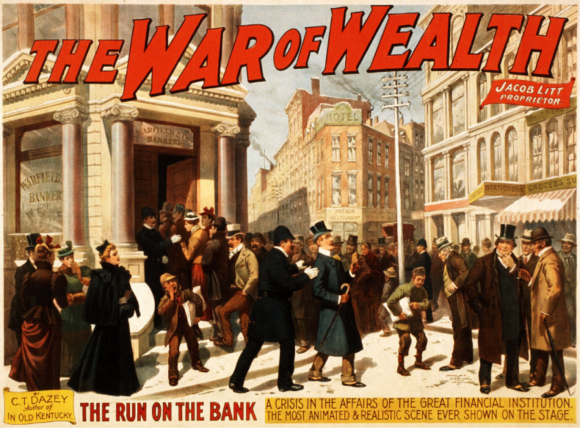

In 1893, a bank panic triggered the worst depression the United States had ever seen. The economy only stabilized after hot-shot financial mogul J.P. Morgan swooped in with an ‘S’ on his chest to save the day. Now more than ever, it was crystal clear that the nation’s banking and financial system needed serious attention and reform.

The 1896 Broadway melodrama The War of Wealth was inspired by the bank panic of 1893.

Source: Wikipedia.org

1907: An Abysmal Year

Saying that 1907 was a very bad year for the stock market could be the understatement of the century. What started as a bout of speculation on Wall Street ended in utter failure, triggering a particularly severe banking panic. Again, tried-and-true J.P. Morgan was called upon to save the American people and avert disaster.

We mentioned that, by this time, most Americans were fed up with the banking system jerking them and their savings around. Everyone agreed that the current system desperately needed some kind of reform, but the structure of that reform deeply divided American citizens between conservatives and progressives.

The one thing they could agree on was that a central banking authority was needed to ensure a healthy banking system and provide for an elastic currency.

1908-1912: A Decentralized Central Bank

An immediate response to the panic of 1907 was the Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908, which would provide for emergency currency issue during crises. Lead by Senator Nelson Aldrich, the commission developed a banker-controlled plan.

Progressives like William Jennings Bryan strongly opposed; they wanted a central bank under public control. The act also established the national Monetary Commission in the hopes of finally finding a long-term solution to the nation’s seemingly endless banking and financial problems.

Alas, the election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson in 1912 effectively killed the Republican Aldrich plan, but the stage was set for a decentralized central bank to emerge.

1912: Creating the Federal Reserve Act

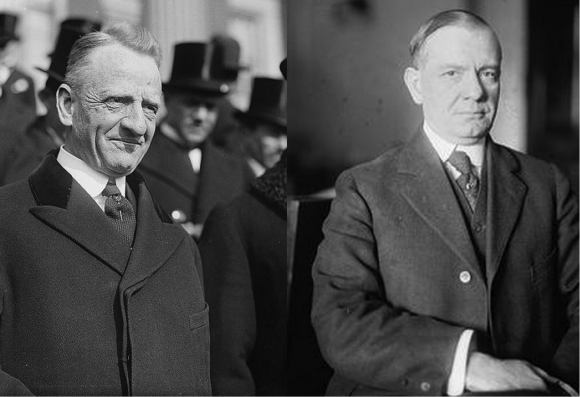

Woodrow Wilson was a far cry from a finance and banking expert, so he wisely sought out expert advice from Virginia Representative and soon-to-be chairman of the House Committee on Banking and Finance, Carter Glass, and H. Parker Willis, a former professor of economics at Washington and Lee University.

Sen. Carter Glass (left) and Rep. Henry B. Steagall, the co-sponsors of the Glass-Steagall Act.

Source: Wikipedia.org

For the majority of 1912, Glass and Willis worked on a central bank proposal, and by December of that year, they presented Wilson with what would become the Federal Reserve Act. The Glass-Willis proposal was intensely debated and modified from December of 1912 to December of 1913.

1913: The Creation of the Federal Reserve System

December 23, 1913, President Woodrow Wilson signs the Federal Reserve Act into law. Many saw this Act as a classic example of compromise—a decentralized central bank that worked to balance the two competing interests of private banks and what the American people wanted.

1914: Come On In, We’re Open

The Reserve Bank Operating Committee was composed of Secretary of Agriculture David Houston, Treasury Secretary William McAdoo, and Comptroller of the Currency John Skelton Williams. It was these three men who had the daunting and unenviable task of building a functioning institution around the brass tacks of the new law before the new central bank could begin operating.

However, come November 16, 1914, 12 cities had been chosen as sites for regional Reserve Banks, and they were open for business. But the timing wasn’t great, as this was just as hostilities in Europe erupted into World War I.

1914-1919: WWI Federal Reserve Policy

Thanks to the emergency currency issued under the Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908, banks continued to operate normally despite the breakout of World War I in mid-1914. The bigger impact in the U.S. came from the Reserve Banks’ ability to discount bankers acceptances.

This allowed the United States to indirectly help finance the war and aid the flow of trade goods to Europe. That is until 1917, when the United States officially declared war on Germany and financing our own war effort became priority number one.

1920s: Open Market Operations – The Beginning

Benjamin Strong (head of the New York Fed from 1914-1928) acknowledged that, following WWI, gold was no longer the central factor in controlling credit. Strong started to buy up a large amount of government securities in an effort to stem a recession in 1923.

To a lot of people, this was a clear indication of the influential power of open market operations on the availability of credit in the banking system.

It was during the 1920s that the Fed started using open market operations as a tool for monetary policy. During his time there, Strong elevated the Fed’s standing by promoting relationships with other central banks, particularly the Bank of England.

1929-1933: The Crash and the Depression

All throughout the 1920s, Carter Glass warned the general public that stock market speculation would lead to dire consequences. But did they listen? In October 1929, he had the displeasure of being right when his predictions proved to be spot-on and the stock market crashed.

What followed was the worst depression in American history.

Nearly 10,000 banks failed from 1930 to 1933, and by March of 1933, freshly inaugurated President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared a bank holiday while government officials desperately tried to fix the nation’s extreme economic problems.

People were angry with the Fed, and blamed them for failing to diminish the speculative lending that led to the crash in the first place. Others argued that a fundamentally inadequate understanding of economics and monetary policy prevented the Fed from going after policies that could have arguably lessened the depth and effects of the Depression.

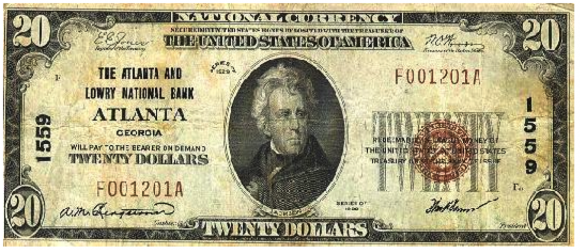

National Bank note issued in 1929 by the Atlanta and Lowry National Bank. The red seal reads, “Redeemable in lawful money of the United States at United States Treasury or at the bank of issue.” At the time, lawful money referred to gold coin, silver coin, gold or silver certificates, or U.S. notes.

Source: www.let.rug.nl

1933: The Aftermath

After the Great Depression, Congress passed the Banking Act of 1933 (or the Glass-Steagall Act) which separated commercial and investment banking, and required government securities to be used as collateral for Federal Reserve notes.

This Act also established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which gave the Fed control over open market operations and required them to examine bank holding companies.

This practice proved to have major future impacts when holding companies became a prevalent structure for banks. Along with all the other massive reforms taking place left and right, Roosevelt went ahead and recalled each and every gold and silver certificate, effectively ending gold and other metallic standards.

1935: Ch-ch-changes

The Banking Act of 1935 required even more changes to the Fed’s structure.

The FOMC was created (Federal Open Market Committee) as an entirely separate legal entity, the Treasury Secretary and the Comptroller of the Currency were removed from the Fed’s governing board, and members’ terms were set at 14 years.

Adding further to the Fed’s list of responsibilities post-WWII, the Employment Act added the goal of promising maximum employment levels.

In 1956, The Fed was named the regulator of bank holding companies owning more than one bank with the passing of the Bank Holding Company Act. In 1978 the Humphrey-Hawkins Act required that the Fed chairman report to Congress twice a year on monetary policy goals and objectives.

1951: The Treasury Accord

After the U.S. entered WWII in 1942, the Federal Reserve System committed to keeping a low interest rate peg on government bonds. This was at the request of the Treasury so the federal government could participate in cheaper debt financing of the war. To maintain the pegged rate, the Fed was forced to give up control of the size of its portfolio as well as the money stock.

Conflict between the Treasury and the Fed became obvious when the Treasury directed the Fed to maintain the peg after the start of the Korean War in 1950.

President Harry Truman and Secretary of the Treasury John Snyder both strongly supported the low interest rate peg. Truman felt it was his duty to protect patriotic citizens by not lowering the value of the bonds that they had purchased during the war.

The Federal Reserve, on the other hand, was focused on containing inflationary pressures in the economy, caused by the growing intensity of the Korean War.

The Fed and the Treasury got into an intense debate for control over interest rates and U.S. monetary policy. They were only able to settle their dispute with an agreement known as the Treasury-Fed Accord. The Fed was no longer obligated to monetize the debt of the Treasury at a fixed rate, and the Accord became essential to the independence of central banking and the Fed pursues monetary policy today.

1970s-1980s: Inflation, Deflation

The 1970s were on an inflation skyrocket to the moon as producer and consumer prices rose, oil prices surged, and the federal deficit more than doubled.

Paul Volcker was sworn in as Fed chairman in August 1979, and, by that time, drastic action was needed to break inflation’s death grip on the United States economy. Like lancing a nasty wound, Volcker’s leadership as Fed chairman in the 80s proved painful in the short term, but successful in bringing the double-digit inflation infection under control overall.

1980: Movin’ On Up! Preparing for Financial Modernization

The Monetary Control Act of 1980 marked the beginning of modern banking industry reforms.

The Act required the Fed to competitively price its financial services against those of private sector providers, and to establish reserve requirements for all eligible financial institutions.

After the Act was passed, interstate banking quickly increased, and banks started to offer interest-paying accounts to attract customers from brokerage firms.

Change was chugging along quite steadily, and, in 1999, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act was passed, essentially overturning the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 and permitting banks to offer an array of financial services that were previously unavailable, including investment banking and insurance.

1990s: A Decade of Economic Expansion

A mere two months after Alan Greenspan took office as the Fed chairman, the stock market crashed on October 19, 1987. Lucky guy. So what does he do? On October 20, he ordered the Fed to issue a one-sentence statement before the start of trading:

The Federal Reserve, consistent with its responsibilities as the nation’s central bank, affirmed today its readiness to serve as a source of liquidity to support the economic and financial system.

When a decade of economic expansion in the 90s came to a close in March 2001, what followed was a short, shallow recession ending in November 2001. After the stock market bubble burst in in the early years of the decade, the Fed moved to lower interest rates rapidly.

The Fed used monetary policy during this time on several occasions – including the Russian default on government securities and the credit crunch of the early 90s – in order to keep financial problems from negatively affecting the real economy.

The hallmarks of the decade were (generally) declining inflation and the longest peacetime economic expansion in United States history.

September 11, 2001

As the terrorist attacks on New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania severely disrupted U.S. financial markets on September 11, 2001, the effectiveness of the Federal Reserve as a central bank was truly put to the test.

The central bank issued a statement very similar to Greenspan’s 1987 announcement:

The Federal Reserve System is open and operating. The discount window is available to meet liquidity needs.

In the following days and weeks, the Fed lowered interest rates and, in order to provide some semblance of stability to the U.S. economy, loaned more than $45 billion to financial institutions.

In rare form, the Fed actually played a critical role in lessening the impact of the September 11 attacks on the American financial markets. As September came to a close, Fed lending had returned to levels seen before 9/11, and a potential liquidity crunch had been successfully avoided. The Fed played the pivotal role in dampening the effects of the September 11 attacks on U.S. financial markets.

Score one for the Fed!

January 2003: Changes in Discount Window Operation

The Federal Reserve changed its discount window operations in 2003 in order to have rates at the window set above the prevailing Fed Funds rate, and to provide rationing of loans to banks through interest rates.

2006 and Beyond: Our Current Financial Crisis and the Response

The American Dream of homeownership was realistically attainable for many more people during the early 2000s, thanks to low mortgage rates and expanded access to credit.

This increased demand for housing drove up prices, creating a housing boom that got a boost from increased securitization of mortgages—a process in which mortgages were bundled together into securities that were traded in financial markets. Securitization of riskier mortgages expanded rapidly, including subprime mortgages made to borrowers with poor credit records.

House prices faltered in early 2006 and then began their steep tumble downward, head over feet, along with home sales and construction. With house prices falling left and right, some homeowners owed more on their mortgages than their homes were even worth.

Starting with subprime and eventually spreading to prime mortgages, more and more homeowners fell behind on their payments. Delinquencies were on the rise, and lenders and investors alike finally got the wake up call that a lot of residential mortgages were not nearly as safe as everyone once believed.

The mortgage meltdown surged on, and the magnitude of expected losses rose dramatically and spread across the globe, thanks to millions of U.S. mortgages being repackaged as securities. This made it difficult to determine the value of loans and mortgage-related securities, and institutions became more and more hesitant to lend to each other.

2007-2008: Lehman and Washington Mutual Fail

The situation reached a fever-pitch crisis point in 2007. Fears about the financial health of other firms led to massive disruptions in the wholesale bank lending market, which caused rates on short-term loans to rise sharply relative to the overnight federal funds rate.

Then, in the fall of 2008, two large financial institutions failed: the investment bank Lehman Brothers and the savings and loan Washington Mutual. Since major financial institutions were extensively intertwined with each other, the failure of one could mean a domino effect of losses through the financial system, threatening many other institutions.

Needless to say, everyone completely lost confidence in the financial sector, and the stock prices of financial institutions around the world plummeted. No one wanted anything to do with them. Banks couldn’t sell loans to investors because securitization markets had stopped working, so banks and investors tightened standards and demanded higher interest rates.

This credit crunch dealt a huge blow to household wealth, and people started cutting back on spending as they wondered what the hell they were going to do about their depleted savings. The snowballing continued as businesses canceled expansion plans and laid off workers, and the economy entered a recession in December 2007. In reality, the recession was pretty mild until the fall of 2008 hit and financial panic intensified, causing job losses to soar through the roof.

2008: The Fed’s Response to the Economic Crisis

By December of 2008, the FOMC slashed its target for the federal funds rate over the course of more than a year, bringing it nearly to zero – the lowest level for federal funds in over 50 years. This helped lower the cost of borrowing for households and businesses alike on mortgages and other loans.

The Fed wanted to stimulate the economy and lower borrowing costs even further, so they turned to some pretty unconventional policy tools.

The Fed purchased $300 billion in longer-term Treasury securities, which are used as benchmarks for a variety of longer-term interest rates like corporate bonds and fixed-rate mortgages. In an effort to support the housing market, the Fed authorized the purchase of $1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by agencies like Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, and about $175 billion of mortgage agency longer-term debt.

So, what does that mean exactly?

Well, these purchases by the Fed have worked to reduce interest rates on mortgages, making home purchases more affordable for everyday Americans.

16 Money Fun Facts – Did You Know?

1. The Constitution only authorized the federal government to issue coins, not paper money.

Article One of the Constitution granted the federal government the sole power “to coin money” and “regulate the value thereof.” However, it said nothing about paper money.

This was largely because the founding fathers had seen the bills issued by the Continental Congress to finance the American Revolution—called “continentals”—become virtually worthless by the end of the war.

The implosion of the continental eroded faith in paper currency to such an extent that the Constitutional Convention delegates decided to remain silent on the issue.

2. Prior to the Civil War, banks printed paper money.

For America’s first 70 years, private entities, and not the federal government, issued paper money. Notes printed by state-chartered banks, which could be exchanged for gold and silver, were the most common form of paper currency in circulation.

From the founding of the United States to the passage of the National Banking Act, some 8,000 different entities issued currency, which created an unwieldy money supply and facilitated rampant counterfeiting.

By establishing a single national currency, the National Banking Act eliminated the overwhelming variety of paper money circulating throughout the country and created a system of banks chartered by the federal government rather than by the states. The law also assisted the federal government in financing the Civil War.

3. Foreign coins were once acceptable legal tender in the United States.

Before gold and silver were discovered in the West in the mid-1800s, the United States lacked a sufficient quantity of precious metals for minting coins. Thus, a 1793 law permitted Spanish dollars and other foreign coins to be part of the American monetary system. Foreign coins were not banned as legal tender until 1857.

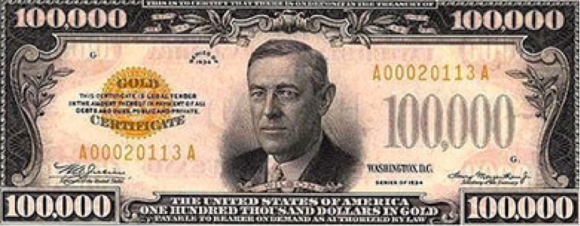

4. The highest-denomination note ever printed was worth $100,000.

The largest bill ever produced by the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing was the $100,000 gold certificate. The currency notes were printed between December 18, 1934, and January 9, 1935, with the portrait of President Woodrow Wilson on the front.

Don’t ask your bank teller for a $100,000 bill, though. The notes were never circulated to the public and were used solely for transactions among Federal Reserve banks. the 100,000 bill, printed between 1934 and 1935

The $100,000 bill, printed between 1934 and 1935.

Source: Wikipedia.org

5. You won’t find a president on the highest-denomination bill ever issued to the public.

The $10,000 bill is the highest denomination ever circulated by the federal government. In spite of its value, it is adorned not with a portrait of a president but with that of Salmon P. Chase, treasury secretary at the time of the passage of the National Banking Act.

Chase later served as chief justice of the Supreme Court. The federal government stopped producing the $10,000 bill in 1969 along with these other high-end denominations: $5,000 (fronted by James Madison), $1,000 (fronted by Grover Cleveland) and $500 (fronted by William McKinley). (Although rare to find in your wallet, $2 bills are still printed periodically.)

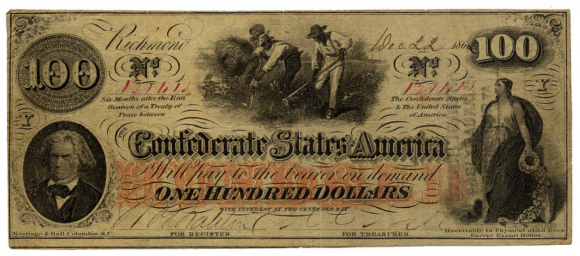

Confederate currency featuring George Washington.

Source: Wikipedia.org

6. Two American presidents appeared on Confederate dollars.

The Confederacy issued paper money worth approximately $1 billion during the Civil War—more than twice the amount circulated by the United States.

While it’s not surprising that Confederate President Jefferson Davis and depictions of slaves at work in fields appeared on some dollar bills, so too did two Southern slaveholding presidents whom Confederates claimed as their own: George Washington (on a $50 and $100 bill) and Andrew Jackson (on a $1,000 bill).

7. Your house may have been built with old money. Literally.

When dollar bills are taken out of circulation or become worn, they are shredded by Federal Reserve banks. In some cases, the federal government has sold the shredded currency to companies that can recycle it and use it for the production of building materials such as roofing shingles or insulation.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing also sells small souvenir bags of shredded currency that was destroyed during the printing process… If you’re into that sort of thing.

8. The $10 bill has the shortest lifespan of any denomination.

According to the Federal Reserve, the estimated lifespan of a $10 bill is 3.6 years.

The estimated life spans of a $5 and $1 bill are 3.8 years and 4.8 years, respectively.

The highest estimated lifespan is for a $100 bill at nearly 18 years.

9. There’s a specific formula for tearing a dollar bill.

According to the federal government, it takes approximately 4,000 double folds (forward, then backward) to tear a note.

10. You can use a torn dollar bill.

More than half of a dollar bill is considered legal tender, and only the front of a dollar is valuable. If you could separate the front of a bill from the back, only the front half would be considered “money.”

11. Spanish dollars were once accepted in the U.S.

During much of the 17th and 18th centuries, the Spanish Dollar coin served as the unofficial national currency of the American colonies.

12. Without coins, the dollar had to be literally cut into parts to make change.

To make change the dollar was actually cut into eight pieces or “bits.” This where the phrase “two bits” comes from.

13. In God We Trust.

These words had first appeared on the United States two-cent coin piece in 1864, and in 1955 a law was passed that all new designs for coin and currency would bear the same inscription, “In God We Trust.”

14. The dollar used to be bigger.

Until 1929, dollars measured 7.42 x 3.13 inches. Since then it has remained at its present size of 6.14 x 2.61 inches, an easier size to handle and store.

Since that size requires less paper, it’s also cheaper to make.

15. The Secret Service was initially established to combat counterfeiting.

By 1865 approximately one-third of all circulating currency was counterfeit, and the Department of Treasury established the United States Secret Service in an effort to control counterfeiting.

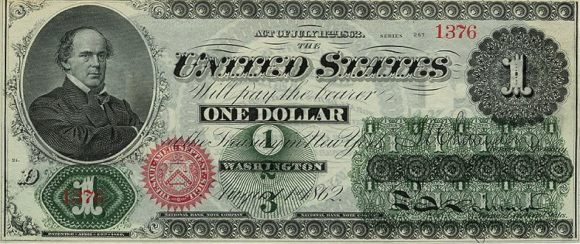

16. Until 1869, the face on the original United States $1 bill is not a president’s.

Salmon P. Chase designed the original US one dollar bill in 1862, and, in what should’ve been the most foolproof marketing strategy of all time, put his own face on the bill in the hopes of fulfilling his presidential dreams. Clearly that didn’t work out so great, but hey, he got Chase National Bank named after him.

À tout à l’heure,

Genevieve LeFranc

for The Daily Reckoning

P.S. Now you have an idea of just how mind-boggling our country’s monetary system can be, and how it got that way. But to help you make the necessary connections between the creation of paper money and your wealth, be sure to sign up for The Daily Reckoning today. It’s a free and entertaining look at the world of finance and politics. The articles you find here on our site are only a snippet of what you receive in our email edition. It’s 100% free, click here now to sign up for FREE to see what you’re missing.

Comments: